A disrupted sleep-wake cycle is not only a symptom but also a contributing factor in mood disorders, according to three studies published in the December 2008 American Journal of Psychiatry (AJP).

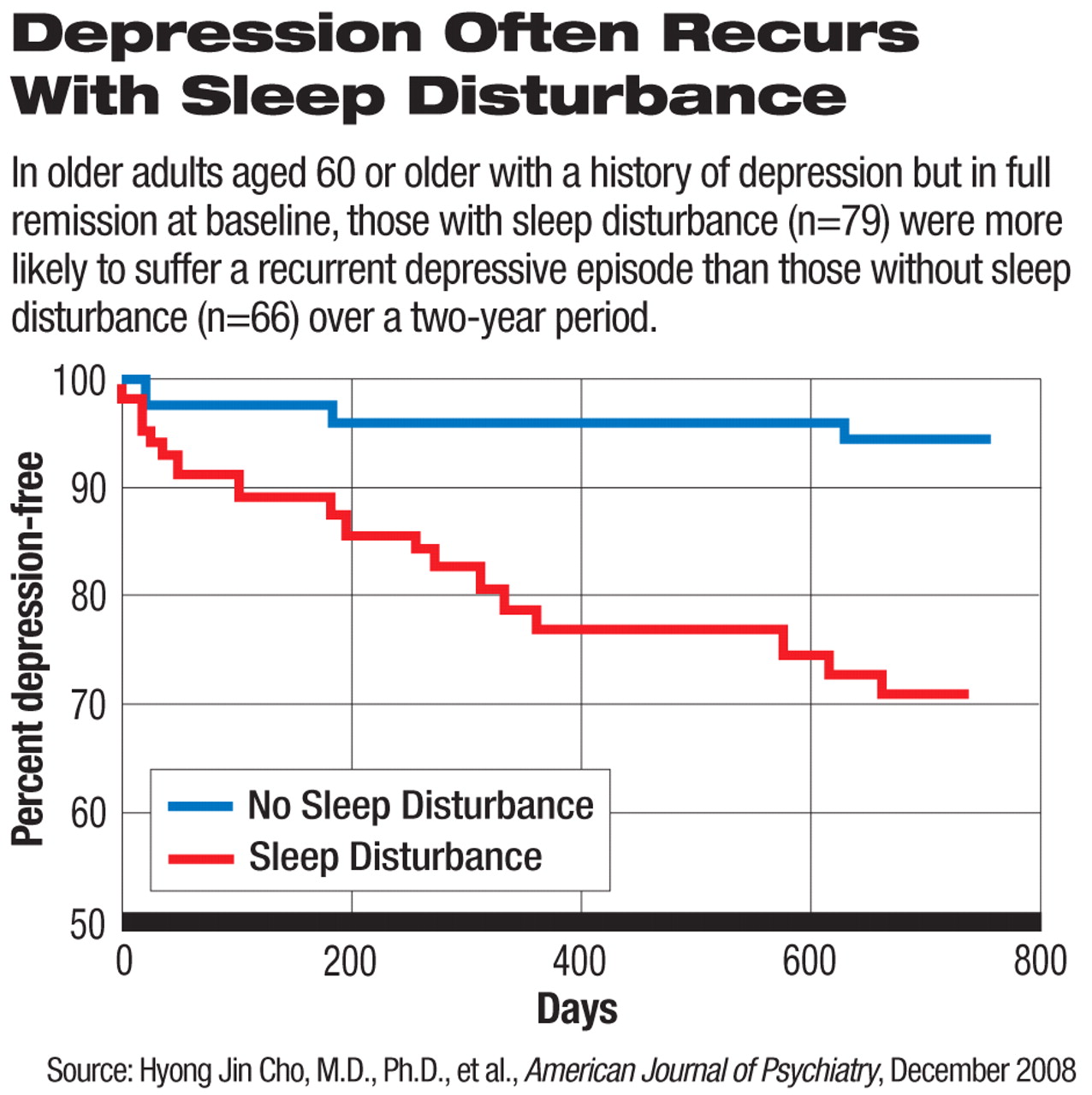

In a study conducted by Hyong Jin Cho, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues, clinically significant sleep disturbance was found to be an independent predictor for a recurrent depressive episode within two years in community-dwelling adults aged 60 or older after controlling for other potential confounding factors such as medication use and other chronic diseases.

Sleep disturbance was defined in this study as a score above 5 on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Although the 145 study participants with a history of depression were in full remission at baseline, sleep disturbance was more common in these subjects (46 percent) than among the 206 control subjects who had no history of depression at baseline (18 percent). In the two-year follow-up, 17 percent of those with a depression history developed recurrent depressive episodes, significantly higher than the incidence of depression (0.5 percent) in those without the history.

Plasma melatonin concentrations showed abnormal patterns in women with depression during and after pregnancy, according to another study published in the same issue by Barbara Parry, M.D., and colleagues. Compared with nondepressed pregnant women (n=15) matched for weeks into pregnancy, the pregnant women with major depression (n=10) had significantly lower levels of melatonin from 2 a.m. to 11 a.m. In contrast, women with postpartum depression (n=13) had significantly higher melatonin levels than nondepressed postpartum women (n=11) across all time intervals.

Melatonin is a hormone synthesized from serotonin in the pineal gland and is known to play an important role in regulating the sleep-wake cycle. Plasma level of melatonin is an indicator of the circadian rhythm. It rises approximately two hours before sleep and decreases during early morning hours.

The same group of authors previously reported study results showing decreased and earlier-shifted melatonin rhythms in women with cyclic mood disturbance before menstruation and higher melatonin levels in women with menopausal depression.

In the third study, Ellen Frank, Ph.D., and colleagues found that bipolar patients randomly assigned to interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (n=61) improved their work functioning significantly faster than patients assigned to intensive clinical management (n=64). At the end of two years of the trial, however, the level of work functioning improved to virtually the same level regardless of the treatment approach.

Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy is a manual-based treatment designed to help patients “stabilize their daily routines and sleep-wake cycles in the hopes of stabilizing endogenous circadian rhythms” and“ resolve interpersonal problems related to grief, role transitions, role disputes, and interpersonal deficits,” the authors explained. Intensive clinical management involved more conventional medical management of bipolar disorder including patient education, nonspecific support, and management of medications and side effects.

The challenge for researchers is to separate the cause and effect between the pathophysiology of mood disorders and disruption of circadian and sleep rhythms as well as to elucidate how mood and sleep interact with each other, Ellen Leibenluft, M.D., chief of the Section on Bipolar Spectrum Disorders in the Emotion and Development Branch, Mood, and Anxiety Program at the National Institute of Mental Health, commented in an editorial in the same issue. For example, it is difficult to determine which is the cause and which the effect between abnormal melatonin plasma levels and depression in pregnant and postpartum women.

Clinical evidence has shown that sleep deprivation has some antidepressant effect and often precedes a manic episode in certain bipolar patients.

Studies of sleep-wake and circadian rhythm disturbance in people with mood disorders “have the potential to suggest novel therapeutic approaches, both pharmacological and nonpharmacological,” Leibenluft wrote. Considering the significant adverse effects of chemical sleep aids, she recommended that clinical studies on “nonpharmacological interventions for the treatment of insomnia should receive serious consideration.”

The editorial, “The Rhythm of the Blues,” and the three studies, “Sleep Disturbance and Depression Recurrence in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Prospective Study,” “Plasma Melatonin Circadian Rhythm Disturbances During Pregnancy and Postpartum in Depressed Women and Women With Personal or Family Histories of Depression,” and “The Role of Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy in Improving Occupational Functioning in Patients With Bipolar I Disorder,” are posted at<http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/content/vol165/issue12/index.dtl>.▪