Suicides among U.S. soldiers are likely to reach a record number this year; however, Army leaders discern some changing patterns that may offer clues to prevention, said Army Vice Chief of Staff Gen. Peter Chiarelli at a Pentagon media briefing on November 17.

The Army reported 140 suicides this year among soldiers on active duty as of mid-November, compared with 143 in 2008. Moreover, 71 suicides were reported this year from among troops not on active duty, such as those discharged or in the Reserve or National Guard.

Suicides in the armed forces are not listed as confirmed until Department of Defense medical examiners investigate each case. Over the last two years, the suicide rate in the military (about 20 per 100,000) has equaled the age-matched civilian rate for the first time.

“This is horrible,” said Chiarelli. “But despite these numbers, we are making progress.”

The timing of suicides this year and the Army's recent expansion of suicide-prevention programs account for Chiarelli's cautiously hopeful assessment.

Forty of the suicides—nearly one-third of the active-duty total—occurred in January, and the overall trend has declined since March, he said. By comparison, there were seven reported suicides among active-duty soldiers in September and 16 in October.

He is briefed individually on every suicide, but no clear and consistent causal issue has emerged, said Chiarelli.

Stress from repeated deployments has been suggested as one cause, but about one-third of the deaths have occurred among soldiers who had never deployed overseas.

Prevention programs have included everything from wallet cards (“Ask, Care, Escort”) to an interactive DVD video to an Army-wide training day last March.

Both seasonal and geographic variations have been observed. For instance, of the 18 suicides recorded this year at Fort Campbell, Ky., 11 occurred between January and April, he said. Of the 10 at Fort Stewart, Ga., six happened during those months.

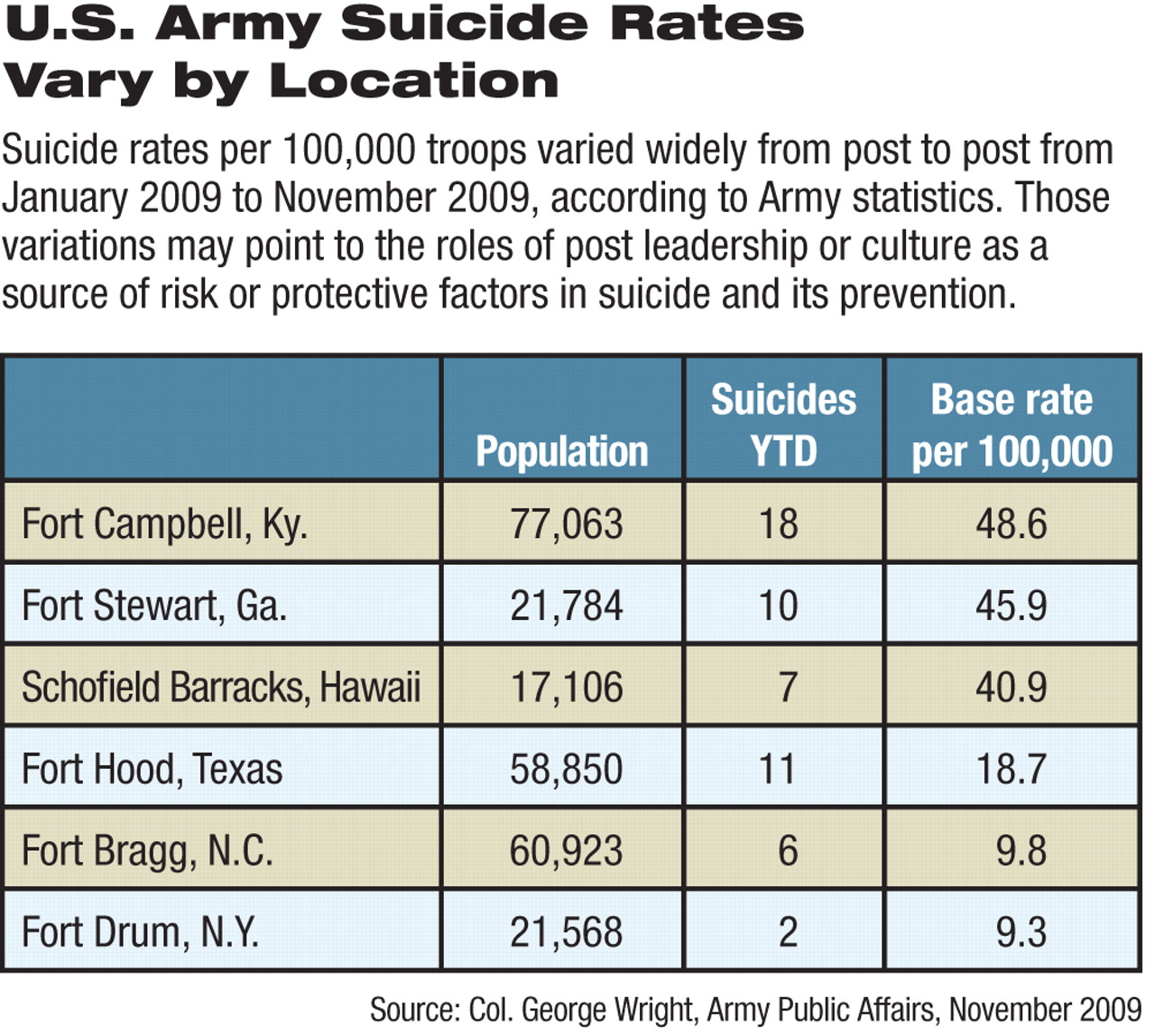

Suicide rates at forts Hood, Bragg, and Drum were higher this year than those at forts Carson and Campbell and at Schofield Barracks. Fort Bragg, N.C., with twice the population of Fort Campbell, had only six suicides (9.8/100,000), compared with the 18 at Fort Campbell (48.6/100,000).

Varying suicide rates between different posts could not be immediately explained, Chiarelli said, but suggest that differences in training, leadership, or culture at the various posts might provide directions for focusing prevention efforts.

Further research may someday explain risk factors for soldier suicide. Scientists conducting a $60 million NIMH-sponsored study of suicide in the U.S. Armed Forces that begun last summer will present a preliminary report to Chiarelli in December, he said.

In addition, the Army began gathering data in October on potential suicide risk factors as soldiers entered the service. In another pilot program, one full battalion returning from war was screened by clinicians for mental health issues at Tripler Army Medical Center in Honolulu, an approach that veterans' groups have long advocated.

The clinicians at Tripler were supplemented by a temporary infusion of others around the country using online computer technology to talk with troops. The screening produced a higher than usual referral rate for further evaluation or treatment, compared with the usual paper-and-pencil screen the Army has been using, said Chiarelli. “The doctors are convinced they can do the screening online, and younger soldiers actually prefer it.”

The Army is also focused on reducing the stigma that interferes with seeking help and on educating soldiers about risky behaviors, such as substance abuse, aggression, and recklessness, he said.

One long-standing approach to the problem of substance abuse is under review. Current policy says that self-referral for drug (but not alcohol) abuse can be reported to the chain of command, which often inhibits solders who want treatment from seeking it.

Now, at three pilot locations the Army is seeing what will happen if such self-referred soldiers can be treated without being reported as drug users to their superior officers. Treatment is limited by a shortage of substance-abuse counselors, however, despite efforts to hire up to 300 more, said Chiarelli.

The Army is also trying to improve soldiers' ability to manage the stresses caused by war and deployment, said Brig. Gen. Rhonda Cornum, Ph.D., M.D., chief of the Army's Comprehensive Soldier Fitness Program.

“We have always paid a lot of attention to physical fitness,” said Cornum. “Now we're trying to educate soldiers in a variety of coping and communication skills and give them an insight into what they think, feel, and do.”

Like physical training, this new effort to develop resilience will eventually be part of every soldier's preparation, not just for those considered at risk, she said. The Army recently held the first in a series of courses in these training techniques for sergeants and junior officers in a venture adapted from a University of Pennsylvania psychology program that melds elements of resiliency training for teachers with sports psychology and the Army's existing Battlemind training. Ultimately, master resiliency trainers will educate others on how to teach the skills to all service members.

“We want to improve soldiers' performance, decrease their anxiety, and reduce catastrophic thinking,” said Cornum.

There may be no simple answer to the problem of suicide, but the Army will press ahead with evidence-based approaches to prevention, said Chiarelli.

“This is the toughest job I've had to tackle in 37 years in the Army,” he said.