Maybe it's the water.

Or maybe it's more complicated than that, but the odds that residents of Las Vegas and visitors to the city will commit suicide appear to be higher than those for people who live or visit elsewhere. Moreover, residents of Las Vegas reduce their risk of dying by suicide when they leave town.

Only three prior studies had looked at suicide risk in Las Vegas, and those were more concerned with the possible role of gambling as a risk factor than exposure to the city itself, said Matt Wray, Ph.D., an assistant professor of sociology at Temple University in Philadelphia, who led the current study. Wray became interested in the subject while on the faculty at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

The study appeared in the December 2008 Social Science & Medicine and was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Health and Society Scholars program.

Wray and colleagues used a variant of a case-control study in which the cases were suicides and the controls were all other deaths. The result is the mortality odds ratio, which can be seen as a risk ratio. They used data from the National Center for Health Statistics and compared the odds of dying by suicide with those for other causes of death and calculated the relative risk of death by suicide.

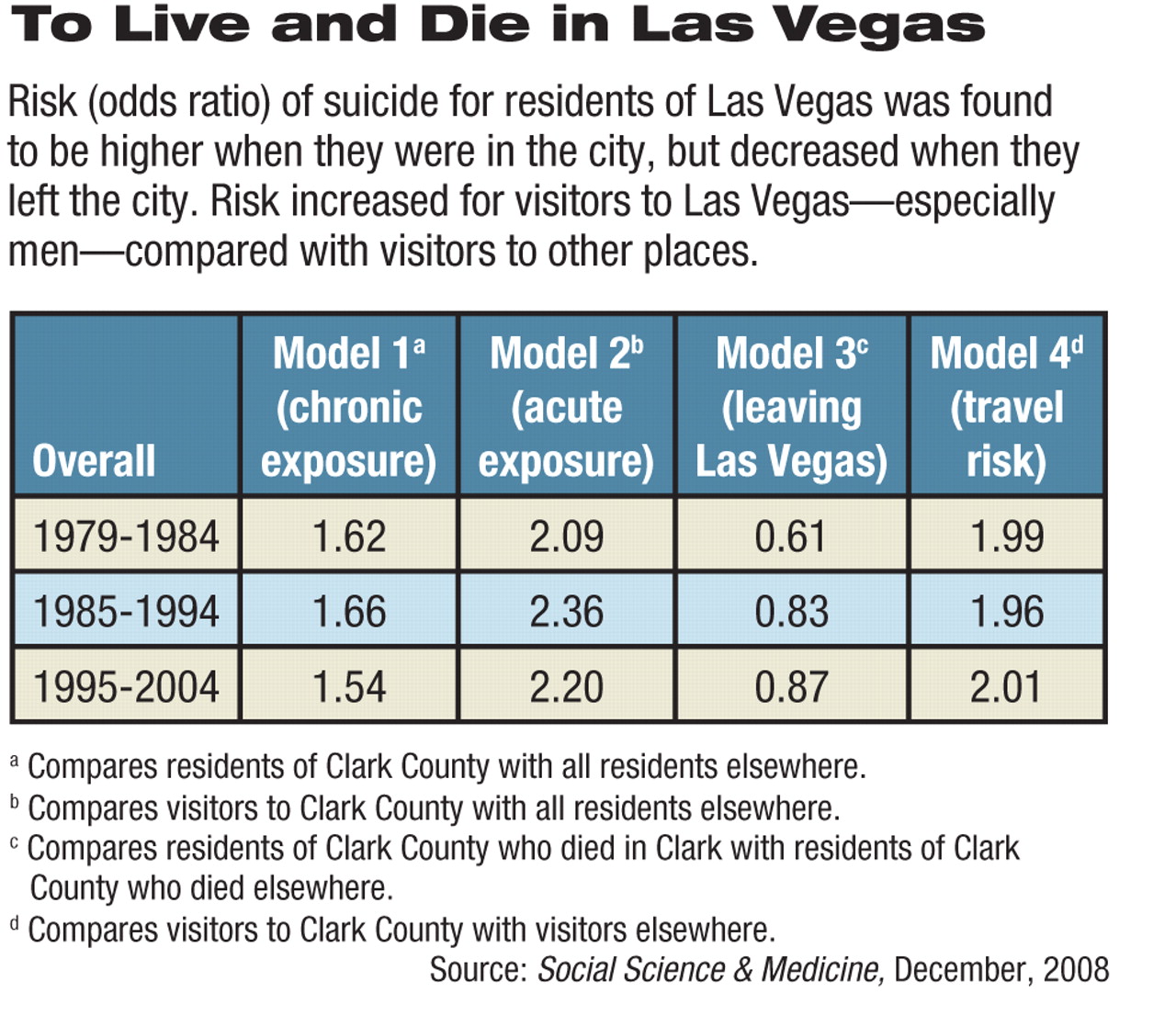

The researchers characterized risk of suicide four ways. “Chronic risk” compared risk of suicide among residents of Las Vegas (Clark County, Nev.) with that of residents of other U.S. counties with a population over 100,000. “Acute risk” was that faced by visitors to the city compared with that of those who stayed home. “Leaving Las Vegas risk” of suicide for city residents who died while away from home was compared with the risk for those who remained at home. “Traveler risk” compared risk for suicide among visitors to Las Vegas with that for visitors to other large counties.

In the most recent decade studied, 1995-2004, suicide accounted for 2.6 percent (n=2,452) of deaths of county residents who died in the county (n=94,278). Suicide accounted for 1.3 percent of all deaths in the United States in 2005, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After adjustment, researchers found that chronic exposure for local residents produced an odds ratio of 1.54, a significantly higher suicide risk for these residents compared with residents living elsewhere. Acute exposure for visitors to the city resulted in an odds ratio of 2.20.

However, for Las Vegans who traveled away from the city, the odds ratio was 0.87, a 13 percent reduction. Finally, traveling to Las Vegas (Clark County) doubled the risk for suicide, compared with travel to other U.S. counties (see chart). In general, men appeared to be at greater risk than women.

Over time, risk of suicide declined slightly for residents and increased slightly for visitors to the city, while the protective effect of leaving Las Vegas declined from 39 percent to 13 percent.

Neither gambling nor the water account for the localized increased in suicide risk, and his study documents an association but not a cause, said Wray.

Gambling Losses Discounted

“The vast majority of persons committing suicide are not reacting to gambling losses, but any attempts at explanation are suppositions,” Paula Clayton, M.D., a psychiatrist and medical director of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, told Psychiatric News.

Another researcher looked at the interaction between hotel registration and suicide in Clark County and found that local people who stayed in hotels there were likely to commit suicide at a rate 16 times that of the general county population.

It's not that hotels cause suicide, said Paul Zarkowski, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral science at the University of Washington in Seattle, in an interview.

“Local people who use hotels may be having a house remodeled, having affairs, throwing parties, or abusing drugs—indicating some disruption in their lives,” he said. “Do they commit suicide in hotels because of the turbulence in their lives or because they want to be first undisturbed and then discovered by a stranger out of concern for family members?”

No one knows, but social disruption in a broader sense may be a contributing factor, these experts agreed.

Until the recent economic downturn, Las Vegas was for decades one of the fastest growing cities in the United States. At times, 6,000 to 8,000 people moved into the area each month.

Region Itself at Greater Risk

“We see a lack of social cohesion in Las Vegas, and people who are not deeply integrated into a community are at higher risk,” said Wray in an interview. “Also, there is a generally higher suicide rate in the intermountain West, for reasons that are poorly understood, but possibly due to cultural values and a go-it-alone mentality that stigmatizes help seeking.”

At least some Las Vegas health officials don't dispute Wray's findings.

“In Las Vegas there is a lack of the family cohesiveness you see in older cities, coupled with a lack of mental health resources,” said Mike Bernstein, M.Ed., a health educator who heads the injury-prevention program at the Southern Nevada Health District. He is careful to note the correlational nature of Wray's paper.

“Thinking about lethal self-harm is not natural,” he said.“ People have to habituate themselves to thoughts of death, but nobody moves to Las Vegas with their family with the thought of committing suicide.”

State and local officials, however, are aware of the problem, said Bernstein. He has run grant-funded programs to counter stigma about mental health care among teenagers and persuade them to get help for friends with suicidal ideation. He also expects the new Nevada Office of Suicide Prevention, recently funded by the state, to put into action plans to reduce the suicide incidence.

“There are people here who care, who do the best we can to advocate for maintaining services,” he said.

Wray intends to continue his exploration of suicide in the Las Vegas area. He will use more detailed data from the coroner's office that include information from family members not covered by the national death records he used in the current study.

“I've spent a lot of time learning from psychological autopsies,” said Wray. “I want to expand that effort to include the social context and the social factors that contribute to the elevated risk of suicide—a kind of social autopsy.”

An abstract of “Leaving Las Vegas: Exposure to Las Vegas and Risk of Suicide” can be accessed at<www.sciencedirect.com> by searching on the study name and then clicking on the study title.▪