One of the best ways in which American psychiatrists can extend mental health care to more Americans is to work together with family doctors, Canadian psychiatrist Joel Paris, M.D., argues in his new book, Prescriptions for the Mind.

But what are the chances of such “collaborative care” between psychiatrists and family doctors becoming a seismic trend?

Actually quite good, according to U.S. psychiatrists who are pioneering and promoting the practice.

The concept of collaborative care, which started about three decades ago in England, was imported into the United States during the 1990s, notably by Wayne Katon, M.D., and colleagues at the University of Washington. Today Katon is a professor and vice chair of psychiatry at the university.

That collaborative care in the United States debuted in Washington was not by chance, Jurgen Unutzer, M.D., also a professor and vice chair of psychiatry at the University of Washington, told Psychiatric News.

“We are the only medical school with a psychiatry training program for a five-state region that makes up a quarter of the land mass of the continental United States.... The only care available to people in this region by and large is primary care. There just aren't enough psychiatrists. So we have to leverage what is a tremendously limited resource and assist our colleagues in primary care in caring for patients with some common mental disorders.”

Early on, Katon and his colleagues applied research principles to the concept of collaborative care to learn whether integrating psychiatrists into a primary care clinic could improve the outcomes of depressed patients. They found that it could. They reported these seminal results in the April 5, 1995, Journal of the American Medical Association.

Since then, they and other researchers have found that partnering between psychiatrists and primary care doctors can help depressed patients (Psychiatric News, June 3, 2005; January 20, 2006; April 7, 2006). To date, there have been 37 trials, Katon said in an interview. “Overall, the trials have shown a dramatic effectiveness of collaborative care, compared with usual primary care.”

And since then, Katon noted, “What people have begun to ask is, 'If this works for depression, might it work for some other mental disorders?' So trials have been launched to find out. For example, two trials have shown that it is very effective for panic disorder. We have also begun testing the model in patients with depression and medical comorbidities, particularly diabetes and heart disease.”

Partnering Has Many Profiles

Partnering between psychiatrists and primary care doctors assumes various profiles. For example, Britta Ostermeyer, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at Baylor College of Medicine, and colleagues have established a collaborative-care program between psychiatrists and primary care doctors at Harris County Hospital in Houston to care for patients with depression or anxiety disorders (Psychiatric News, March 17, 2006).

“We are furthering the scope of what the primary care physicians do,” she explained. “We want them to diagnose mental illnesses, make referrals for those patients whom they cannot properly treat or address themselves, and then when a psychiatrist stabilizes those patients and refers them back, they continue the care. So that is one aspect. The other aspect is that there are patients who do not need to be seen by a psychiatrist.... The primary care doctor seeks a 'curbside' consultation with the psychiatrist and then goes back and treats the patient.”

Such collaboration, initially only research based, is becoming routine clinical practice in several places. Count Ostermeyer's program among these, along with the groundbreaking approach at the University of Washington where psychiatrists practice within most of the university's large primary care clinics.

In California, the large HMO Kaiser Permanente has integrated psychiatric staff into all of its primary care clinics. This means that collaboration between psychiatrists and primary care doctors has become a standard benefit for some 6 million Californians who receive health care through Kaiser. A project at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) called the Tides and Waves Project is expanding its partnering between psychiatrists and primary doctors to VA outpatient clinics throughout the country.

Probably the most groundbreaking collaborative-care operation that is moving beyond research into clinical practice is the Diamond Project in Minnesota. It is run by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, which is working to get routine depression screening with the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) established in some 25 large primary-care groups and in some 90 clinics in Minnesota. The institute is also working to get eight health insurance companies to pay for such screening, as well as for the services of psychiatrists, primary care doctors, and case managers who assist in treating the screened patients found to be depressed.

And more is coming. “All sorts of places around the country are looking into doing collaborative care by bringing primary care and psychiatry together at one location,” Ostermeyer observed.

Reimbursement Is Major Hurdle

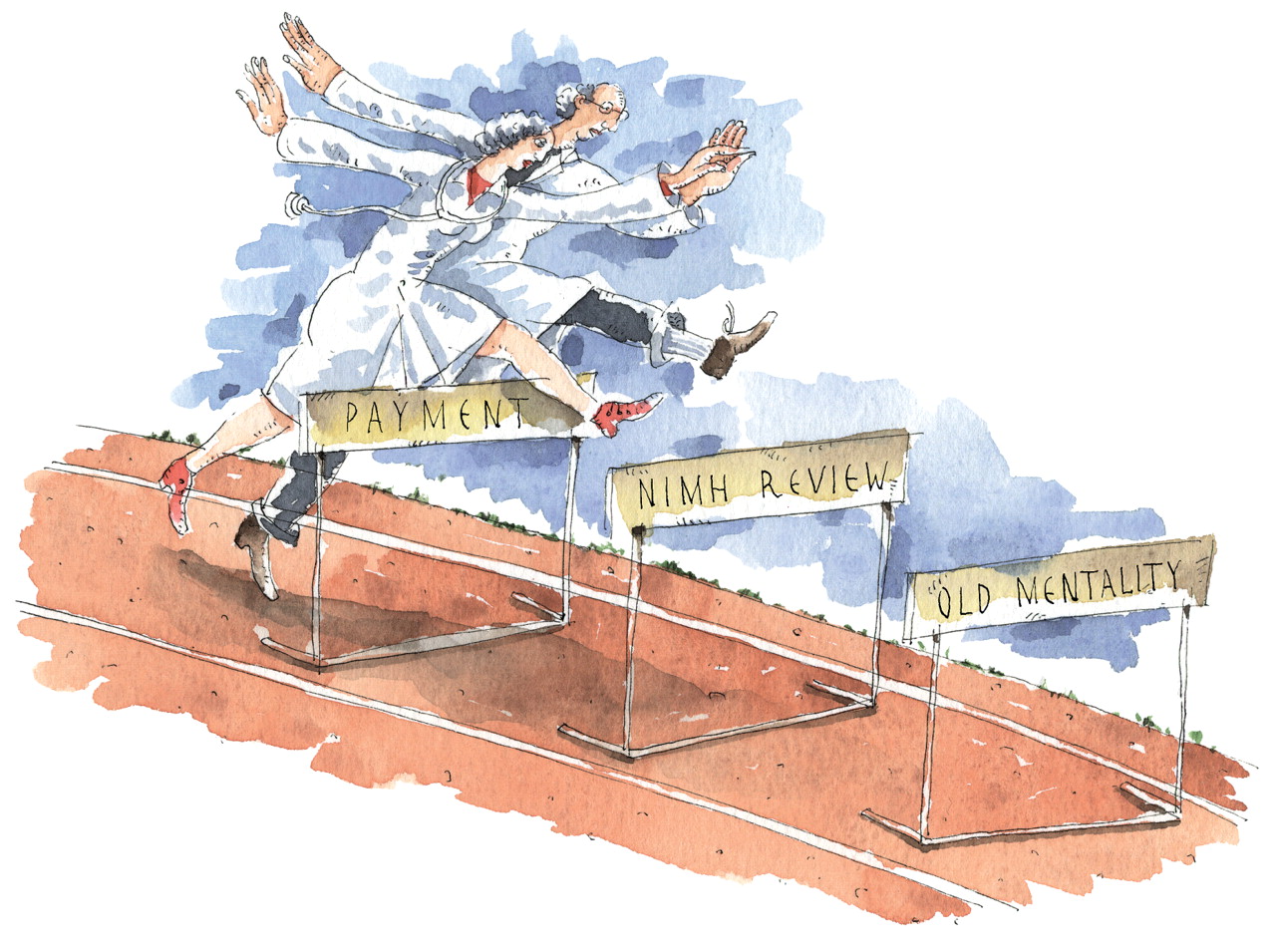

In the rush to transform psychiatrists and primary care doctors into confreres, experts agree that several hurdles need to be overcome.

“I think the biggest challenge is payment,” Unutzer said, adding that although some insurance companies are making it easy for primary care clinics to adopt the collaborative-care model (Psychiatric News, January 20, 2006), others are not.

A second obstacle is getting collaborative-care models past review sections at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) or the VA. “Most people who sit on review sections at the NIMH or at the VA,” Katon said,“ tend to be 'splitters' or 'lumpers.' Splitters are people who want you to do something in a very narrow population very well. Lumpers are people” who want you to do something for more people with the resources available.

A third barrier to be overcome is to “change the mentality of primary care physicians, especially some of the older generation,” Ostermeyer noted. “Some are not comfortable prescribing psychiatric medications.”

“Effectiveness studies have shown that you can improve patient outcomes dramatically by using algorithms to make sure that patients are getting evidence-based care and then to refer them to specialty care if they are not meeting certain criteria,” said David Katzelnick, M.D., a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin. Yet he also noted that getting such algorithms implemented in collaborative-care clinics is tough. In other words, there are two separate challenges. One is convincing primary care doctors that using algorithms is worthwhile. The other is actually getting them to put algorithm information into patients' medical records so that psychiatrists and other health care providers have access to it.

Collaboration Brings Many Rewards

Nonetheless, partnering between psychiatrists and primary doctors has its compensations.

“Our patients are absolutely thrilled that they can walk into their neighborhood primary-care center and get psychiatric care,” Ostermeyer attested. “It removes the stigma that surrounds walking into a psychiatric clinic.”

“Primary care patients really like getting results from the PHQ-9,” Katzelnick reported. “The PHQ-9 is also very helpful in communicating with primary care clinicians and in advising them on depression treatment.”

“For me, the main reward is that I feel that I am providing better patient care,” Unutzer remarked. “I am providing care to whole patients, not just to their minds or emotions. For example, if a patient says, 'I hurt all over,' I can address the depression and then work with a primary doctor to address the arthritis pain.”

“Part of the gratification for me,” Katon noted, “is that we psychiatrists are able to treat a much wider portion of the population than we would otherwise be able to treat.”

The best in the psychiatry-primary care partnership may be yet to come.

“We are seeing a dramatic expansion of it now, and I think that is going to continue because there is going to be more demand from regulators, insurance, and the government to provide evidence-based care,” Katon predicted.

“Certainly many large health care settings, like the VA and the large HMOs, but also many federally qualified health centers that serve low-income, uninsured, safety-net populations are moving toward integrating mental health specialists into their clinics,” Unutzer observed. “So I think we will see more of this. I think we will start to train psychiatrists to work in these kinds of settings. I also think we are going to see more of the reverse—those of us who practice in mental health specialty settings are going to find ways of inviting our colleagues in [primary care] medicine to help care for our [seriously, persistently ill] patients.”

“I hope that collaborative care will become the standard of care within the United States and that reimbursement of clinicians will be restructured to support it,” Katzelnick asserted. “I think that is starting to happen. The Diamond Project is an example.... If that goes well, it will spread throughout Minnesota, and I know that Wisconsin is also looking at it.”

“I think there is a bright future for collaborative care because both primary care and psychiatry realize that they need each other,” Ostermeyer said. “For the new generation of primary care doctors, it will be normal and natural for them to treat mental illness, just as they treat cardiac conditions.” ▪