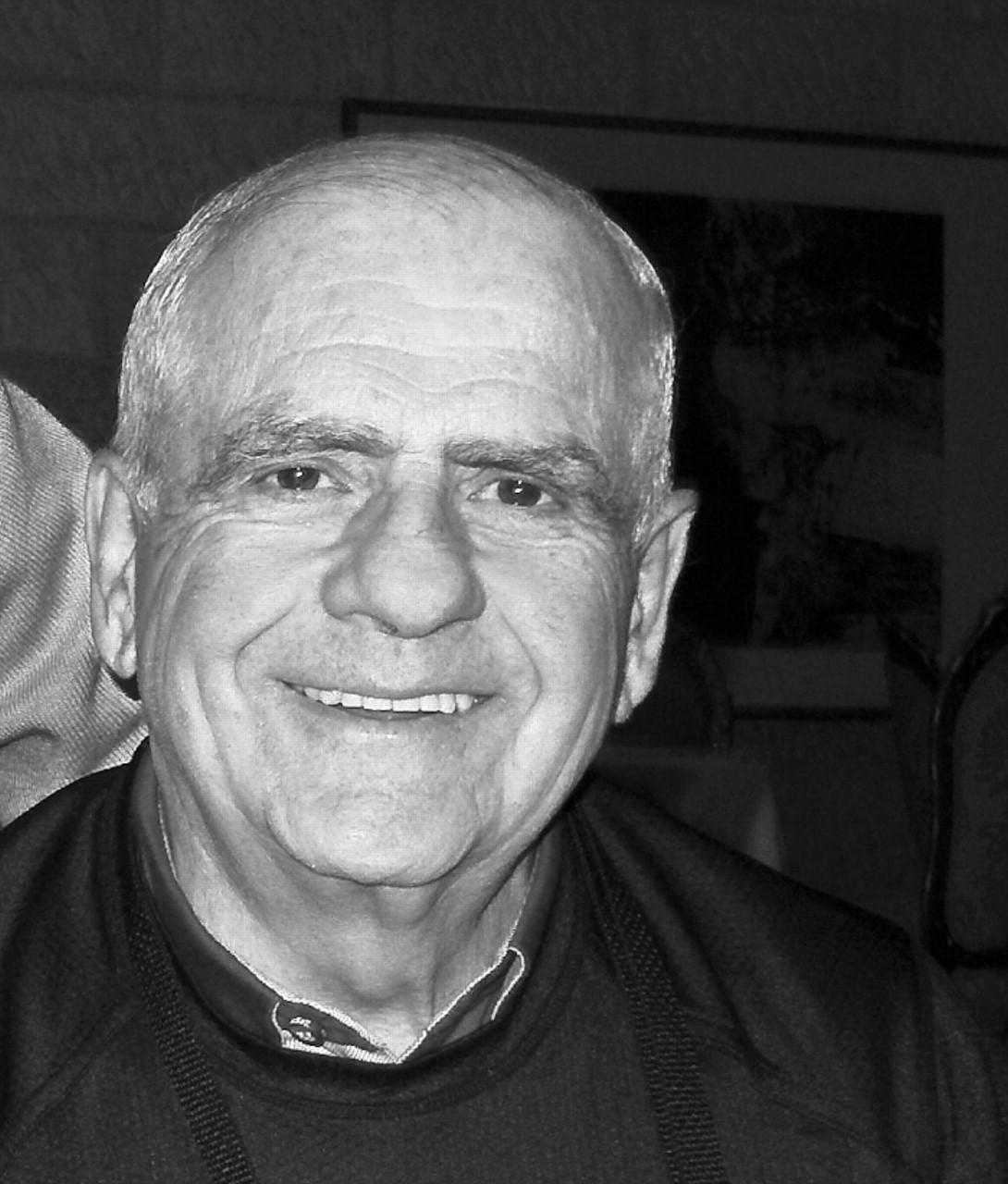

Gerald Schneiderman, M.D.'s first glimpse into the mysteries and silences of the Holocaust began as a child at the outset of World War II.

His parents sent packages to relatives in Russia, said the Toronto child psychiatrist in a recent interview. “But nobody talked about it when the thank-you letters stopped coming back.”

In the late 1960s, he evaluated Holocaust survivors who had immigrated to Canada. More recently, Schneiderman traveled to Poland on an educational trip that led him back to the secrets of a group of survivors six decades after the war's end.

These were “hidden children,” saved from ghettos and concentration camps when their desperate parents passed them along to non-Jewish Poles. While their lives were saved, the children often began a tortuous lifelong relationship with truth, deception, and secrecy, which came to intrigue Schneiderman at both the personal and professional levels.

Secrecy was a necessary way of life during the war, when the mere fact that the children were Jews had to be kept from neighbors and authorities because disclosure would mean death for the children and their protectors. Many of the youngest children never knew they were Jewish. Many others learned to keep that knowledge to themselves as they grew up, not just during the war but afterward, too, in the face of repeated waves of anti-Semitism in Poland. Only with the fall of Communism in 1990 did some feel sufficiently comfortable to disclose the fact of their ancestry.

“We don't know how many Jewish children survived the war,” said psychologist Eva Fogelman, Ph.D., the daughter of Holocaust survivors. She helped organize the first conference on child survivors in 1991, in an interview. “Not all children were given back to parents [if they survived] or to representatives in Jewish organizations. Sometimes children left in convents or monasteries were kept because the nuns or priests felt more strongly about saving souls than reuniting families.”

Many children orphaned by the Holocaust stayed with their adopted families. Some knew about their heritage; many, especially the youngest, did not.

To understand the experience of these children, Schneiderman collaborated with University of Warsaw psychology Ph.D. candidate Magda Budziszewska to interview 20 child survivors or their children or grandchildren in three Polish cities. All had dealt in some way with their own decision or that of their adoptive parents to hide their status as Jews.

For some of these individuals, that meant not telling their children or grandchildren that they had been born Jewish. For others, it meant learning only when their adoptive parents were literally on their deathbeds.

“I wanted to assess the effects, if any, that the revelation of their backgrounds might have had on these individuals,” Schneiderman said.

A 77-year-old man was raised as a Catholic and didn't tell his children of his—and their—Jewish roots until they were adults. A 71-year-old woman never knew she was Jewish until an aunt tracked her down and told her.

A man in his 50s learned only when he was 40 that his father was Jewish and had escaped the Warsaw Ghetto as a 9-year-old. The father wanted to protect his children from anti-Semitism. After his son learned the truth, he began seeing a therapist to better understand his father's choices and his own life.

Schneiderman also spoke with people who are now in their 20s and 30s. Several had visited Israel and established a connection with Jewish culture.

“I heard their stories, but I did not do a clinical evaluation of anyone,” said Schneiderman. “None appeared to have symptoms of mental disorder, although many certainly had internal struggles with the way their lives had worked out.”

“The biggest problem, emotionally, was how do you begin to relate to your parents—alive or dead—if they've lied to you your whole life?” said Fogelman. “That affects your ability to trust in intimate relationships.”

Another Canadian psychiatrist understands clearly what these children experienced. Robert Krell, M.D., now retired and living in British Columbia, was born in Holland. A family friend protected him during the Nazi occupation. His parents were saved by others, and they were reunited after the war before immigrating to Canada.

“Many of these people say that they always felt there was something different about them in comparison to their siblings and presumed parents,” Krell told Psychiatric News. “But that observation was never commented on when they were growing up. Their primary response to learning about their history was relief that there was a reason for their feelings and—for some—their earliest memories.”

Schneiderman also believes his interviewees benefited from disclosure.

“All of them felt better,” he said. “They now feel part of a cultural system. All became interested in the cultural or intellectual aspects of Judaism, although not usually in the religious or communal side.”

“Secrecy is a two-edged sword,” said Krell, who has not met Schneiderman. In addition to healing, learning the truth of one's ancestry may engender the regret at not knowing sooner, of a lost continuity, and of not being able to impart Jewish tradition to their children, Krell said.

At the same time, the lifesaving necessity for the deception is also clear, which makes the moral and psychological contradictions ultimately comprehensible.

He noted, “I was taught to lie by the most truthful person I ever knew”—the adoptive mother who saved his life in World War II.

The Web site of the World Federation of Child Survivors of the Holocaust is <www.wfjcsh.org>.