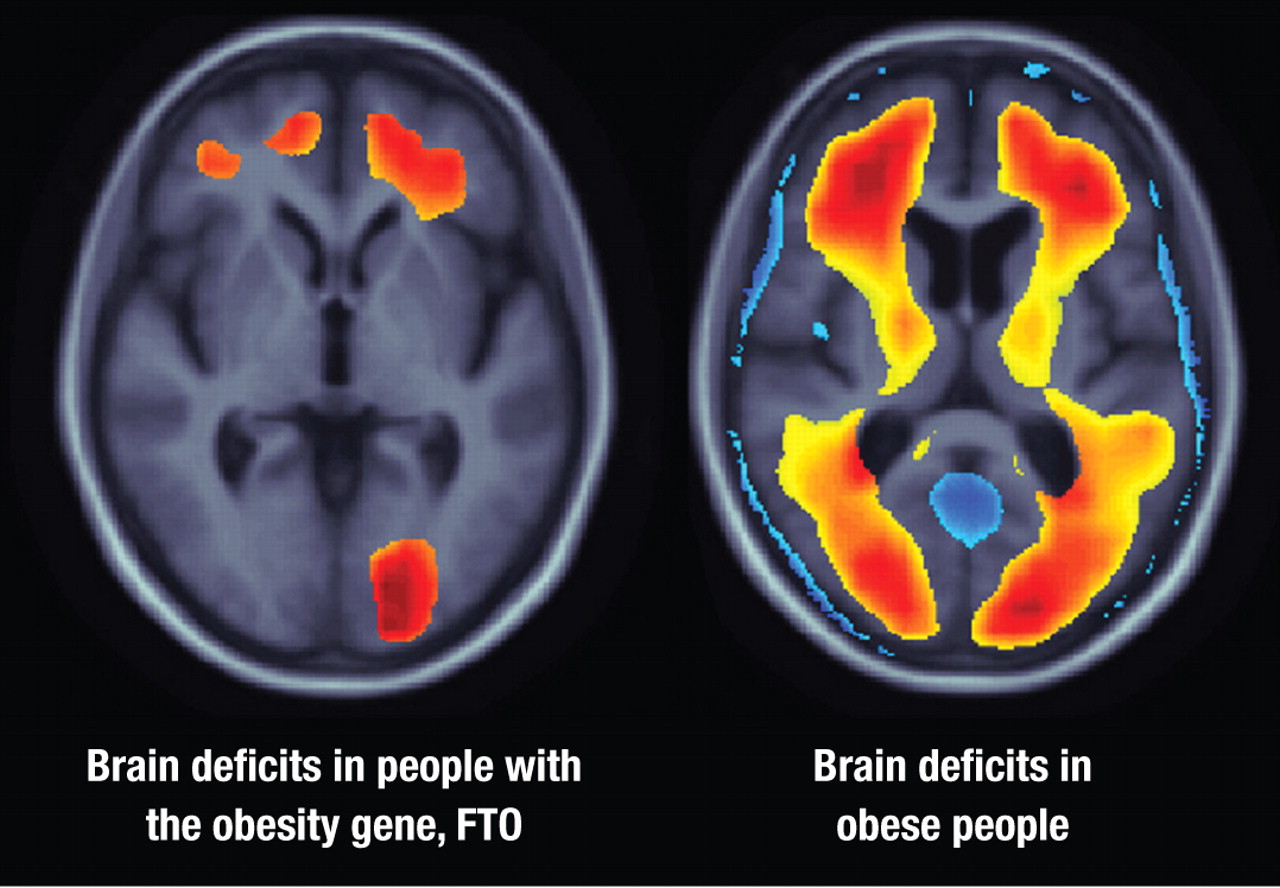

Could a “fat” gene lead to a “skinny” brain? That may be the case since a gene variant that predisposes to obesity has been linked to volume loss in several brain areas.

Senior author Paul Thompson, Ph.D., a professor of neurology at the University of California at Los Angeles, and colleagues published their findings online April 19 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

During the past three years, several groups of scientists have found that 51 percent of people of West African ancestry, 46 percent of people of European ancestry, and 16 percent of people of Chinese ancestry carry a gene variant that predisposes to weight gain. The gene is called the FTO gene. People who have one copy of this gene variant weigh, on average, 4.5 pounds more than people who do not have it, and people who have two copies of the variant weigh nine pounds more than people who do not have it.

The FTO gene is also known to be expressed in the human brain. Moreover, some studies have linked a higher body mass index with brain-volume loss. So Thompson and his team wondered whether possession of the FTO gene variant might be associated with brain-volume loss.

They selected as their subjects 206 cognitively healthy subjects aged 70 to 90 who had already been genotyped as part of the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. This initiative was a large five-year study aimed at better understanding factors that resist disease as the brain ages.

Out of the 206 subjects, 128 had one or two copies of the weight-predisposing FTO gene variant; the remaining 78 did not. The two groups were comparable in age, education, cholesterol level, blood glucose level, and a history of high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and stroke.

The scientists then used MRI scans and a relatively novel method called applied tensor-based morphometry to generate three-dimensional maps of the brain volumes of their subjects. Finally, they compared outcomes of the two groups.

There was 8 percent less tissue in the frontal lobes of carriers versus noncarriers of the gene variant, and 12 percent less tissue in the occipital lobes of carriers versus noncarriers—both significant differences.

Thus possession of the weight-predisposing FTO gene variant might lead to a reduction in volume in certain areas of the brain, the researchers concluded. And if that is the case, what are the clinical implications?

One possibility, they suggested, is that the gene variant could lead to poor executive functioning, since frontal lobe volume deficits have been linked with decreased executive functioning, and since obese individuals have been found in general to have poorer executive function than their nonobese counterparts.

Another possibility, they noted, is that the gene variant might help set the stage for dementia. Other studies have found that obesity is a risk factor for dementia in general and for Alzheimer's disease in particular.

“We now want to determine whether the obesity-gene variant influences the brain volume of people of various ages or only of a certain age,” Oscar Lopez, M.D., told Psychiatric News. Lopez, a professor of neurology and psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, was a coauthor of the study. “The next step will be to go after people who are age 85 or older.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, several pharmaceutical companies, and several nonprofit organizations.

An abstract of “A Commonly Carried Allele of the Obesity-Related FTO Gene is Associated With Reduced Brain Volume in the Healthy Elderly” can be accessed at <www.pnas.org> by entering the title in the “advanced search” box.