Next time you want to get a good chuckle, don't tell people to “tickle your funny bone,” but to “tickle your nucleus accumbens.”

This suggestion is based on the results from a study by Ihtsham Haq, M.D., an assistant professor of neurology at Wake Forest University, and published online March 10 in NeuroImage.

It all started while Haq's mentors at the University of Florida—neurosurgeon Kelly Foote, M.D., psychiatrist Wayne Goodman, M.D., and neurologist Michael Okun, M.D.—were implanting a deep brain stimulation (DBS) device in the internal capsule-nucleus accumbens region of a patient to treat her treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. As the physicians tested electrodes in the device, they received a surprise—the patient laughed.

Haq, who was present during the implantation, asked his mentors whether he could analyze smile responses not just in this patient, but in the five others with treatment-resistant OCD in whom they were planning to implant the device. This way, he hoped, he might obtain new insights into the biological substrates of human mood and emotion. Foote, Goodman, and Okun gave him permission to proceed, and they received IRB approval to do so.

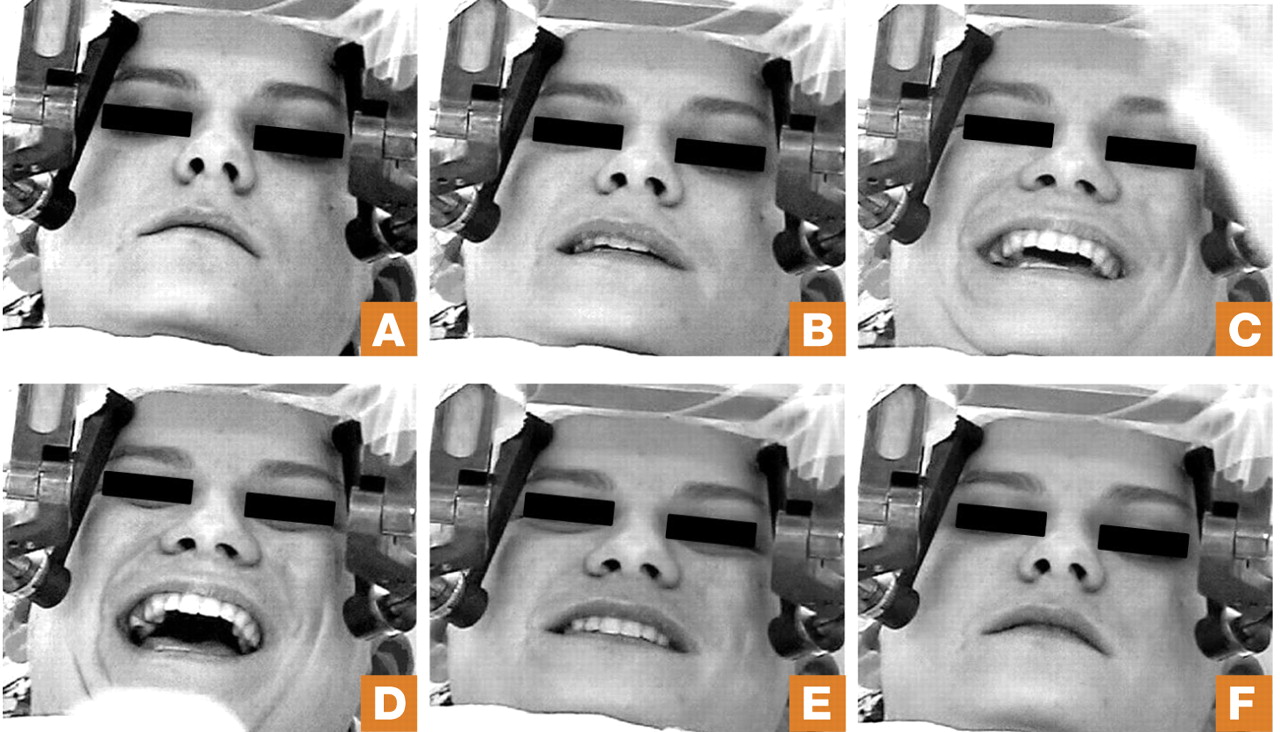

While this patient and the five others were being implanted with the DBS device, Haq, with the help of Foote, Goodman, and Okun, used the device to stimulate various regions of the internal capsule-nucleus accumbens, then evaluated the reactions of the patients to these stimulations.

Five of the six patients experienced at least one smile response during testing. At higher voltages of stimulation, some of these smiles progressed to laughter. One patient said, “I'm trying to keep a straight face.” Moreover, smiles and laughter were associated with mood elevation in the patients. “I feel like I've just won a cruise,” one patient said. The smile-laughter-euphoria-inducing sites were located relatively medial, posterior, and deep within the internal capsule nucleus accumbens.

Thus, whereas the nucleus accumbens was already known to be the reward center of the brain, this particular “sweet spot” may be part of the brain's smile, laugh, and euphoria center, Haq and his colleagues concluded.

Foote, Goodman, and Okun also evaluated the patients for obsessive-compulsive symptoms two years after the DBS device had been implanted in their brains. Haq then looked to see whether there was any significant link between the number of times they had smiled or laughed upon internal capsule-nucleus accumbens stimulation and their obsessive-compulsive disorder outcome.

There was no link apparent for smiles, but there did appear to be one when it came to laughter. The more patients had laughed upon stimulation, the fewer symptoms they had two years later.

“Intraoperative stimulation-induced laughter may predict long-term obsessive-compulsive response to DBS,” Haq and his colleagues concluded. And a possible explanation for it, they proposed, is that the “sweet spot” in the nucleus accumbens that produces laughter is also “a region that ameliorates obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms when chronically stimulated.”

Yet “if clinicians decide to use stimulation-induced laughter to predict obsessive-compulsive disorder improvement, it will need to be done soon after device activation,” the researchers advised. That is because they were able to induce such laughter only in the operating room or at the first postoperative visit, not during subsequent test-stimulation sessions.

Indeed, “identifying other potential response predictors for obsessive-compulsive disorder will become increasingly important as more patients are implanted with DBS devices,” they noted. DBS was approved by the Food and Drug Administration a year ago to treat refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder (Psychiatric News, March 20, 2009).

The study also raises the question of whether there might be a link between the ability to laugh and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The researchers believe that there might be. Other researchers reported that individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder had difficulty laughing, and that medical treatment for the disorder helped reinstate the individuals' ability to laugh.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Parkinson Foundation Center of Excellence.

An abstract of “Smile and Laughter Induction and Intraoperative Predictors of Response to Deep Brain Stimulation for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder” can be accessed at <www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/10538119> by clicking on “Articles in Press.”