Aspirin beat a placebo as an adjunctive medication for schizophrenia in an intriguing new study.

William Carpenter Jr., M.D., a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Maryland and editor in chief of Schizophrenia Bulletin, calls the finding “exciting.”

“The question of infectious, immune, and/or inflammatory pathophysiology in schizophrenia is old, but interest has increased recently,” Carpenter explained to Psychiatric News. “This is especially relevant to therapeutic discovery where novel targets and mechanisms are needed to supplement six decades of dopamine antagonists as antipsychotic drugs.... Replication [of this study] is essential, but if successful, a new treatment approach is introduced, and a new window for therapeutic discovery is opened.”

The study was headed by Wijnand Laan, Ph.D., an assistant professor at the University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, and was reported in the May Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. The goal was to see whether adding aspirin to antipsychotic medications could reduce symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia.

The study sample consisted of 70 subjects with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Half were randomly allocated to a test group and the others to a placebo group. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scores for the two groups were comparable. The only differences between the two groups were that the duration of illness was slightly shorter and the proportion of those treated with clozapine slightly higher in the placebo group.

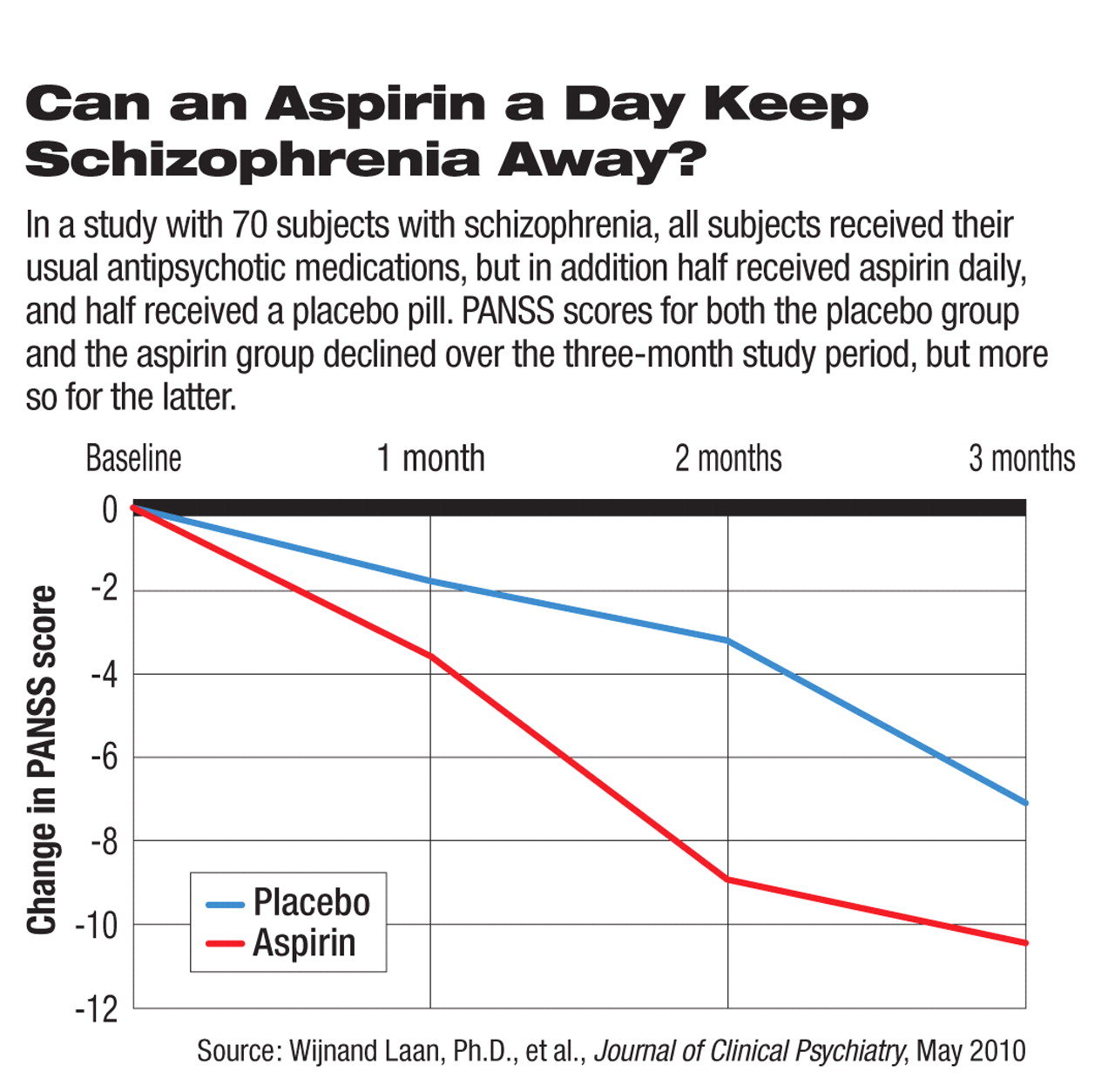

All subjects continued to receive their usual antipsychotic medications during the three-month study period, but the test group also received 1,000 mg of aspirin daily, while the placebo group received an identical-appearing placebo daily.

During a three-month follow-up period, the PANSS was again used to evaluate the subjects for schizophrenia symptoms. Before and after the study, subjects were also given cognitive tests. Results from baseline and the follow-up period were compared.

Positive PANSS scores and total PANSS scores for both groups declined, the researchers found, but more so in the aspirin group; the differences were statistically significant. For the positive PANSS score, the difference was 1.57 points, and for the total PANSS score, the difference was 4.86 points, differences that the researchers described as “of medium size.”

Negative PANSS scores for both groups also declined, and again especially in the aspirin group, but these differences were small and not statistically significant. No effect of aspirin on cognitive function could be detected.

If aspirin may be able to reduce schizophrenia symptoms, how might it do so? By correcting an imbalance in the production of pro-inflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines by helper T cells, the researchers proposed. Other researchers have implicated such an imbalance in schizophrenia.

Thus, “given the considerable effect of aspirin over three months, the refractory character of symptoms while on antipsychotics alone, and the safety of aspirin, this drug might become a useful addition to regular treatment,” the scientists concluded.

The findings also raise the question of whether aspirin as a stand-alone treatment might benefit schizophrenia patients. Unfortunately, this question cannot be easily answered, the researchers wrote, “since it would be unethical to randomly assign patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders to placebo alone.”

The study was funded by the Stanley Medical Research Institute.