Though many newer antipsychotic drugs are on the market, clozapine is still considered by many psychiatrists to be the drug of choice for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. In fact, it should be initiated after two or three other antipsychotic drugs have failed, according to a 2004 APA practice guideline.

In addition, clozapine is the only medication the Food and Drug Administration has approved to reduce the risk of suicide in patients with schizophrenia (Psychiatric News, December 6, 2002).

Nonetheless, clozapine appears to be underutilized in many countries. And a new survey conducted in Denmark and published in the July Journal of Psychopharmacology suggests that Denmark is one of the countries where that trend is evident.

The study's lead investigator was Jimmi Nielsen, M.D., a researcher at Aalborg Psychiatric Hospital in Aalborg, Denmark.

The study cohort included 100 psychiatrists whose average age was 54 and who had been in practice an average of 20 years. “We only have one health care system in Denmark, so all were working at public psychiatric hospitals,” Nielsen told Psychiatric News.

Of the 100 psychiatrists participating in the phone survey, which was conducted from November 2006 to March 2007, 48 percent had responsibility for fewer than five patients treated with clozapine, and only 31 percent had started clozapine treatment within the three months prior to the survey. Seven percent had never prescribed clozapine even though they were not newly minted psychiatrists. In other words, they were between the ages of 41 and 53 and had worked at least five years in general psychiatry. Sixty-four percent said that they would rather combine two other antipsychotics than use clozapine.

So if Danish psychiatrists are often adverse to prescribing clozapine, what might be the reasons? Nielsen and colleagues offered several possible explanations based on what they learned from their study.

For example, most survey responders were aware that, according to most schizophrenia practice guidelines, clozapine should be initiated after two or three antipsychotics have failed. However, many did not appear to be well-informed about other aspects of clozapine use. For example, 54 percent knew that the risk of the acute blood disorder agranulocytosis from clozapine use is between 0.5 percent and 1 percent, but 23 percent overestimated the risk.

Only 33 percent of respondents knew that the agranulocytosis risk is greatest within the first six months.

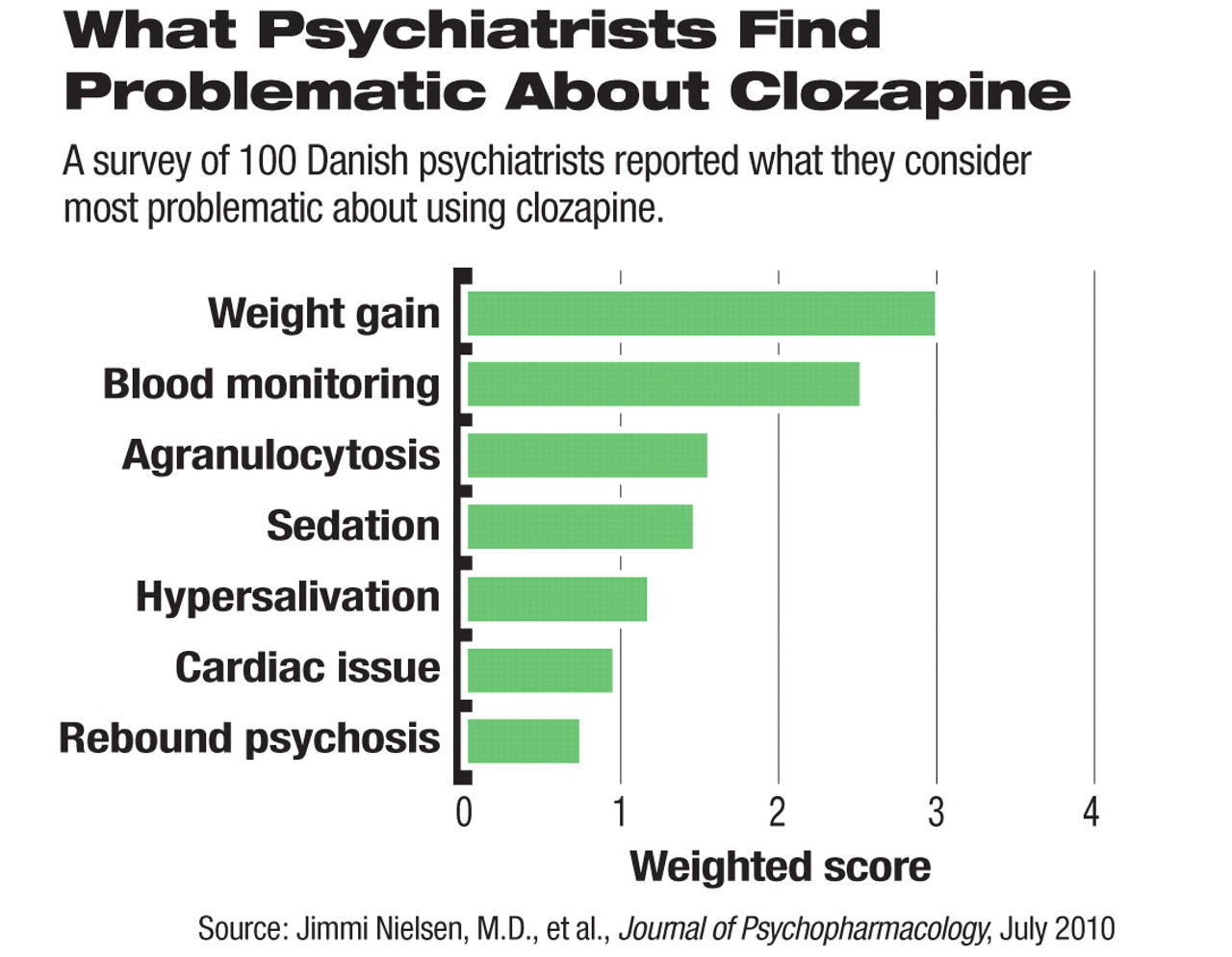

Responders rated weight gain as the most problematic aspect of prescribing clozapine, though according to several clinical studies, clozapine does not cause any more weight gain than the widely used second-generation antipsychotic olanzapine does. (Of course, as is the case with olanzapine, the fact that clozapine does cause weight gain is likely to be a concern to psychiatrists in deciding which antipsychotic to prescribe.)

In addition, many survey responders considered the need to do routine blood monitoring a problematic aspect of prescribing clozapine. This was the case even though all were working in hospital settings and could have conducted routine blood monitoring more easily than psychiatrists working in privatepractice settings. In fact, survey responders rated the need to do routine blood monitoring the most problematic aspect after weight gain (see chart).

Two-thirds of responders said that their patients were less satisfied with clozapine than with other second-generation antipsychotics, although other studies have found that the quality of life of patients on clozapine is comparable to that of patients on other newer antipsychotics.

“I think this was the most surprising finding,” Robert Buchanan, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland and a schizophrenia expert, told Psychiatric News. “I wonder whether it represents the psychiatrists' projections of their own concerns about clozapine onto the patients? Or it might reflect the fact that the average clozapine dose [used] was 350 mg/day, which is a little bit low for a treatment-resistant population.”

“I was also surprised by how comfortable survey responders felt in engaging in various non-evidence-based polypharmacy practices, yet by their reluctance to use the only evidence-based medication we have for treatment-resistant schizophrenia and suicidality,” Buchanan said.

So what is the future of clozapine in psychiatry? “I think there is a real danger that, unless some structural changes are made in resident education, clozapine's use will continue to decline,” Buchanan suggested. Nielsen and his colleagues concurred. Yet another way of keeping clozapine in use, Buchanan said, might be for psychiatrists with ample clozapine experience to serve as consultants to colleagues who have less such experience.