Difficulty breathing related to asthma or to transient air pollution may contribute to risk for suicide, according to two large Asian population studies.

One of the studies found that Taiwanese teenagers with asthma had a significantly higher incidence of suicide than peers without the disorder. And the second study found that a transient increase in particulate matter in the atmosphere is associated with increased risk for suicide, especially among those with cardiovascular disease.

The two reports, “Asthma and Suicide Mortality in Young People: A 12-Year Follow-Up Study” and “Ambient Particulate Matter as a Risk Factor for Suicide” were posted online in AJP in Advance on July 15.

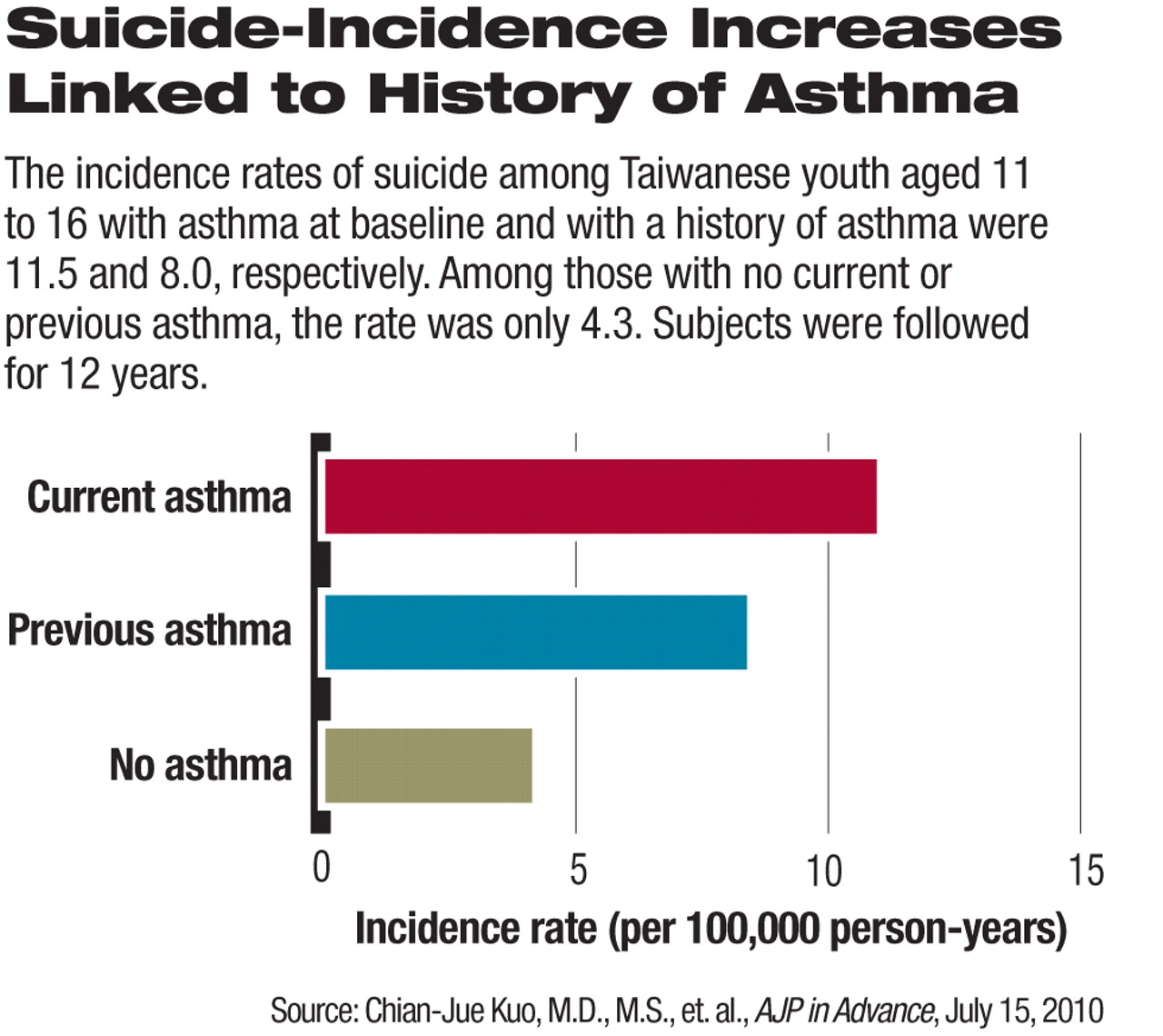

The first report on teenage suicide found that among Taiwanese adolescents aged 11 to 16 followed for 12 years, the incidence rate of suicide in participants with asthma at baseline was more than twice that of those without asthma. At the same time there was no significant difference in the incidence of natural deaths, a finding that strengthens the association between asthma and suicide.

Moreover, having a greater number of asthma symptoms at baseline was associated with a higher risk of suicide, according to the report.

“Our study highlights that young people with asthma have an elevated risk of suicide mortality, especially those with more severe and persistent asthma symptoms,” lead author Chian-Jue Kuo, M.D., M.S., told Psychiatric News. “Physicians treating adolescent patients who have asthma should inquire about the psychological burden associated with the disease, and suicide risk should be evaluated periodically. Psychiatric consultation is suggested if physicians detect a patient with a significant psychological burden, mental illness, or suicide risk.”

In the study, 162,766 high school students aged 11 to 16 living in a catchment area in Taiwan from October 1995 to June 1996 were enrolled in a study of asthma and allergy. Participants were classified into three groups at baseline: those with current asthma, previous asthma, and no asthma. Participants were followed to December 2007, and in cases of death, causes were tracked by the linkage to Taiwan's national Death Certification System.

By December 31, 2007, 905 participants had died, with 106 of those listed as suicides. Of the 106 suicides, 37 occurred among patients with asthma at baseline or with a history of asthma. The incidence rate of suicide among participants with asthma at baseline or a history of asthma was 18.5 compared with just 4.3 for those with no asthma (see chart).

Study co-author Cleusa Ferri, M.D., acknowledged that the study did not measure depression—or presence or history of other mental illness—at baseline. However, she said the researchers did perform a “sensitivity analysis” in which they adjusted for depression by assuming a prevalence of depression among adolescents with asthma derived from previous studies.

The sensitivity analysis demonstrated only a small potential confounding effect on the association between asthma and suicide. But Ferri said it is possible that depression may play a mediating role in suicide—individuals who developed depression after baseline might, for instance, have been more likely to interpret respiratory symptoms as a serious medical disorder, especially when symptoms were persistent and severe. (The sensitivity analysis is posted online at AJP in Advance as a data supplement to the article.)

“Our main findings have a clear importance for public health and potential preventative measures,” Ferri, who is with the Institute of Psychiatry at Kings College, London, told Psychiatric News. “Obviously the ideal would be to prevent asthma, and among those with asthma to prevent suicide, or depression if it has an important mediating effect.”

In the second report, on air pollution and suicide, 4,341 suicides that occurred in 2004 in seven cities in the Republic of Korea (South Korea) were temporally matched with hourly mean concentrations of particulate matter. Statistical analysis was used to associate percentage increases in suicide risk with increases in particulate matter, and a subgroup analysis was performed to stratify suicides by underlying disease (cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and psychiatric illness).

Researchers from the Department of Preventive Medicine and the Institute for Environmental Research at the Yonsei University College of Medicine in Seoul found a 9 percent increase in suicide risk related to an increase in particulate matter of 10 micrometers (approximately the size of a fog or cloudwater droplet) or less 0 to 2 days prior to the day of suicide.

They also found a 10 percent increase in suicide associated with an increase in particulate matter of 2.5 micrometers or less, one day prior to the day of suicide.

(The United States Environmental Protection Agency regulates pollution consisting of particulate matter with diameters larger than 2.5 micrometers and smaller than 10 micrometers and “fine particles” with diameters that are 2.5 micrometers and smaller.)

After stratification of suicide cases by underlying disease, a statistically significant association between 10-micrometer particulate matter and suicide risk was observed among individuals with cardiovascular disease, but not among those who did not have cardiovascular disease including those with psychiatric illness, according to the report.

“Although a significant association between ambient particulate matter and suicide was observed in this study, we can only speculate on the reasons for it,” wrote lead author Changsoo Kim, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues in the report. “The observed association might be due to neurotoxic substances of ambient particulate matter components, such as lead, mercury, diesel exhaust particles, and manganese.

“Increased particulate matter can affect mental health by contributing to the worsening of physical health and aggravation of chronic diseases,” the authors wrote. “High concentrations of particulate matter can trigger various diseases, and epidemiologic study has demonstrated that the presence or worsening of chronic illness increases the risk of suicide.”

“

Asthma and Suicide Mortality in Young People: A 12-Year Follow-Up Study” and “Ambient Particulate Matter as a Risk Factor for Suicide” can be accessed at <http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/pap.dtl>.