The 8 million younger Medicare beneficiaries with permanent disabilities—including serious and persistent mental illness—face more difficulty affording medications and accessing care than do the majority of Medicare beneficiaries—those who qualify because they are aged 65 or older, according to a recent survey.

An analysis of a 2008 nationally representative survey of Medicare participants published in the August 12 Health Affairs found that because of cost and access difficulties, beneficiaries under age 65—those who qualify for Medicare coverage through the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program—reported more adverse health consequences, according to the authors.

The report, by Juliette Cubanski, associate director of the Medicare Policy Project at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), and Patricia Neuman, a vice president of KFF, identified problems more specific to people with mental illness. About one-third of the 8.9 million people receiving SSDI in 2009 had a diagnosed psychiatric illness, according to the Social Security Administration. Younger beneficiaries qualify for Medicare coverage under SSDI if their disability leaves them unable “to engage in substantial gainful activity because of any medically determinable permanent physical or mental impairment,” according to the program's rules.

The challenges faced by these younger Medicare beneficiaries include higher rates of multiple chronic illnesses than other Medicare beneficiaries. Half of nonelderly beneficiaries reported five or more chronic health conditions, while only about one-fourth of the elderly Medicare recipients had this many chronic conditions.

The differences in access to care and costs of care between the two Medicare populations start with differences in supplemental “Medigap” insurance, which covers most of Medicare's out-of-pocket costs. According to the survey data, nearly 1 in 4 nonelderly Medicare beneficiaries lacks supplemental coverage—twice the proportion in the older group.

In one area critical to people with serious mental illness—prescription-drug coverage—disabled nonelderly Medicare recipients appeared to have somewhat better coverage than older Medicare beneficiaries. In 2008, 88 percent of nonelderly disabled beneficiaries had prescription drug coverage, compared with 84 percent of the elderly ones.

The medical care needs of younger Medicare beneficiaries also appeared significant. Nonelderly disabled beneficiaries reported higher utilization rates of inpatient hospitalization, as well as more emergency room and office or clinic visits. In addition, a higher share of nonelderly beneficiaries reported receiving mental health care or counseling, likely due to higher reported rates of mental health conditions compared with elderly Medicare beneficiaries, the authors noted.

More Access Problems Identified

Despite the greater medical needs of the younger Medicare population, they reported higher rates of access problems—including difficulty finding medical care providers, getting appointments, and finding transportation to those appointments.

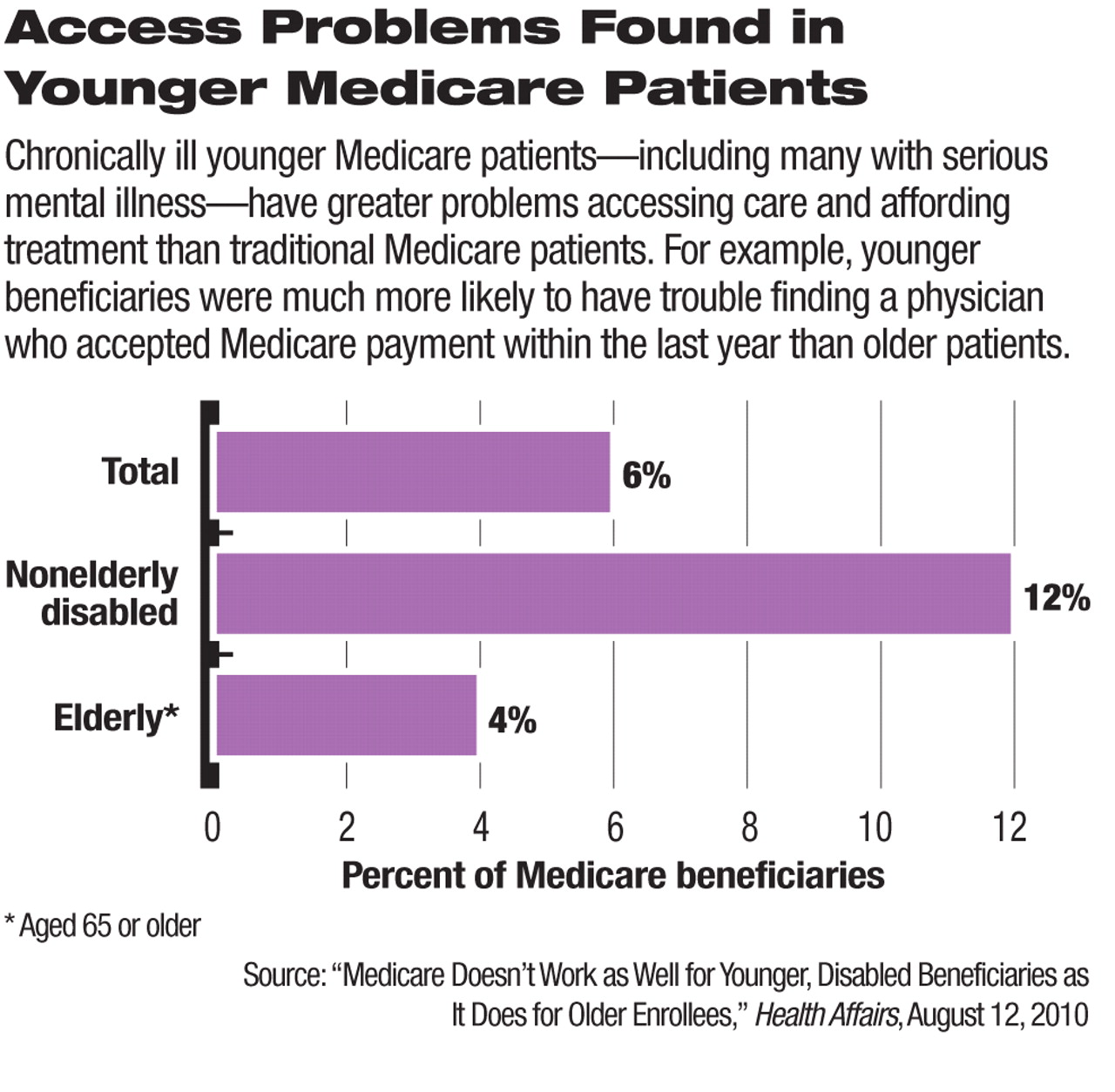

While only 6 percent of Medicare beneficiaries overall reported having difficulty finding a physician who accepted Medicare, the rate was three times higher for younger Medicare beneficiaries than older ones. In addition, 15 percent of nonelderly beneficiaries reported difficulty finding physicians who understood their disability or how to treat it.

Access was further impeded for younger beneficiaries by affordability concerns. While less than 20 percent of the elderly beneficiaries reported problems paying for health care services and put off or did not get care because of cost concerns, roughly half of nonelderly Medicare beneficiaries delayed care over cost concerns.

Cost-related barriers to treatment were most likely to affect younger beneficiaries' use of dental services, followed by prescription drugs—a key component in the treatment of many serious mental illnesses.

Financial challenges led nearly 60 percent of younger Medicare beneficiaries who lacked supplemental coverage to report problems paying for one or more health care services, including prescription drugs, doctor visits, and hospital services. About 40 percent reported spending less on basic needs so they had money to pay for health care.

Health Reform Likely to Improve Situation

The access and affordability challenges faced by younger Medicare beneficiaries may improve as the recently enacted national health care overhaul is implemented over the next several years. The measure may especially help people with disabilities by broadening access to public and private health insurance coverage and improving Medicare Part D coverage.

Until the reforms are fully implemented in 2014, uninsured adults with preexisting conditions will have access to subsidized coverage through new national or state-run high-risk pools. This feature of the health care overhaul could ease the medical impact of the two-year waiting period that people with serious mental illness must endure before they are eligible for SSDI Medicare coverage.

Starting in 2014, the new health insurance law also will require people with disabilities—along with all other Americans—to obtain individual coverage. But many with serious disabilities are expected to qualify at that point for Medicaid, which will offer expanded access nationwide for anyone whose income is up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level. Additionally, new private health insurance exchanges will offer subsidies to offset the costs of coverage, and comprehensive insurance market reforms such as age-rating limits will help reduce longstanding barriers to coverage, according to the survey authors.

However, the new law will not address all of the needs of younger Medicare beneficiaries. “Even with health insurance, people with disabilities are likely to face ongoing challenges if their coverage, including Medicare, does not provide the services and supports they need to live as independently and productively as possible,” Cubanski and Neuman noted.