Functional brain imaging of women with postpartum depression showed decreased activity and less connectivity in and between brain regions associated with the ability to read and respond to emotional cues.

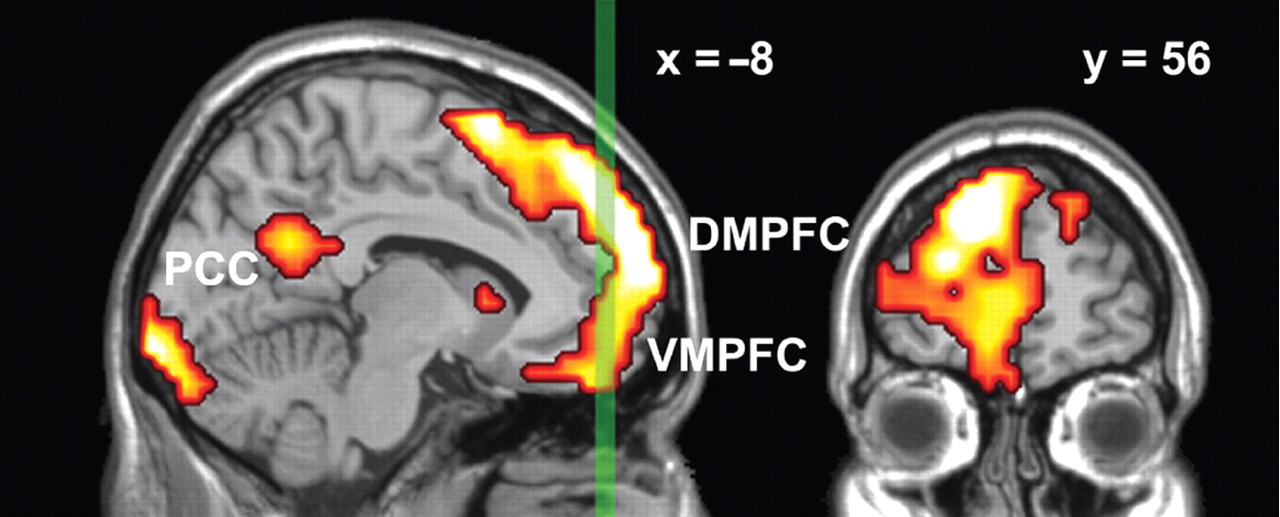

Depressed mothers who viewed pictures of scared or angry faces had significantly reduced activity in the left dorsomedial prefrontal cortical (DMPFC) area of the brain compared with healthy mothers shown the same pictures. And they also showed less communication between the DMPFC and the amygdala.

The findings were reported online in AJP in Advance on September 15.

Moreover, the more severe postpartum depression symptoms were in the mothers, the less activity they demonstrated on imaging in the left amygdala; and the more they experienced “infant-related hostility,”—feelings of irritation or anger associated with caring for the infant—the less activity they showed in the right amygdala.

Lead author Eydie Moses-Kolko, M.D., said the study, though sampling only a small number of women, is among the first to look at brain imaging in postpartum depression, and the data suggest that some symptoms experienced by women with postpartum depression may be related to a deficit in the neural networking between the DMPFC and the amygdala.

“In this small study we have identified a circuit of interest that may suggest diminished arousal to emotional stimuli in women with PPD [postpartum depression], while individuals with depression often have the reverse—oversensitivity to emotional stimuli,” she told Psychiatric News. “Clinicians could be mindful that there are subsets of women with PPD who display these characteristics and that these symptoms might be worth inquiring about in a clinical setting.

“It is possible that some women with PPD have disengagement of the DMPFC-amygdala circuit and are not as attuned to distress signals from the infant,” she said. “In this way, the mother-infant ‘dyadic dance’ may be less well synchronized, and infants may not learn as readily how to regulate their own arousal, but this has not yet been formally tested.”

Moses-Kolko is an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Fourteen depressed and 16 healthy mothers were enrolled and then imaged while performing a standard perceptual face-matching task that involved matching “target stimuli” with a face; for comparison, both groups also performed a shape-matching task, in which they matched shapes while being imaged. Subjects were four to 13 weeks postpartum on the scan day and were hormonal-contraception-free, with the exception of one woman who had a levonorgestrel intrauterine device inserted six days prior to the scan. Depressed mothers had not taken antidepressant medication for at least two years prior to the time of the scan.

Healthy mothers showed significantly more activity in the DMPFC than did depressed mothers in response to the face-matching task. And while activity in response to the shape-matching task was minimal for both groups, it was greater in depressed mothers than in healthy mothers.

Additionally, in healthy mothers, there was significant connectivity from the left dorsomedial prefrontal cortex to the left amygdala reference region, indicating a dominant influence of this region on the left amygdala in response to faces. In contrast, no connectivity was observed between the left amygdala and any neural region of interest in depressed mothers, the researchers noted.

“The DMPFC is known for its role in social cognition and empathy, so this region helps people understand the intentions and feelings of others,” Moses-Kolko said. “We think this is particularly important for new mothers who are caring for an infant that cannot articulate its needs. Mothers become very good at understanding infant cues in order to respond to their needs, so we would expect most mothers to have active DMPFC regions when exposed to emotionally arousing stimuli.

“We hope this line of work will help to identify a range of neural circuitry responses to emotional stimuli in larger groups of women with PPD,” she added. “Additional studies will be needed to examine which neural patterns are modifiable with pharmacologic, behavioral-psychotherapeutic, or hormonal treatments.”

“Abnormally Reduced Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortical Activity and Effective Connectivity With Amygdala in Response to Negative Emotional Faces in Postpartum Depression” is posted at <http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/pap.dtl>.