Ecstasy might take some of the agony out of psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), if findings from a phase 2 pilot study are any indication.

Outcomes of the small, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial indicated that MDMA, better known by its street name of ecstasy, may be useful as an adjunct to psychotherapy for patients with chronic, treatment-resistant PTSD.

However, overcoming objections to using an outlawed compound may present difficulties, even if efficacy is verified.

The federal government categorized MDMA as a Schedule I controlled substance in 1985, although it was sometimes used earlier as an experimental medication in conjunction with psychotherapy.

MDMA has been shown to induce feelings of “euphoria, increased well-being, sociability, self-confidence, and extroversion,” according to a report by principal investigator Michael Mithoefer, M.D., and colleagues published online July 19 in the Journal of Psychopharmacology. Mithoefer is in private practice in Mount Pleasant, S.C.

The trial was sponsored by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) in Santa Cruz, Calif. Staff members of MAPS, including Mithoefer, are among the authors of the paper. Approval for the study had to be obtained from both the Food And Drug Administration and the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Whatever its immediate effects, use of MDMA may produce long-term neuropsychiatric damage in some individuals, according to Harold Kudler, M.D., a VA psychiatrist and associate director of the VISN 6 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center in Durham, N.C., who was not involved in this research.

“Safety is a concern, given MDMA's association with neuropsychiatric, emotional, and cognitive difficulties,” said Kudler, in an interview with Psychiatric News. “Also, subjects taking part in such studies may be at increased risk for subsequent abuse of MDMA and related compounds.”

The most effective treatment now used for PTSD is exposure therapy. However, revisiting traumatic experiences in therapy may be limited by the patient's inability to tolerate those memories. Recall may cause emotional numbing, which prevents the engagement that would lead to fear extinction, said Mithoefer.

A drug that could widen the range between the extremes of fear and numbing might improve the action of psychotherapy, said the authors.

The use of MDMA helps maintain the patient in a state in which he or she is neither over- nor under-aroused psychologically. Either state is a poor emotional environment for recalling and discussing traumatic experiences as part of therapy, Mithoefer said. The drug generally gives four or five hours for the patient to process fear, grief, or rage associated with their trauma without being overwhelmed.

“This is different from most drug studies in that it is really drug-assisted psychotherapy,” Mithoefer told Psychiatric News. “The drug is not taken alone but while the patient is under the therapist's supervision.”

The researchers randomized 23 treatment-resistant patients with crime-related PTSD into two groups. Both groups received two 90-minute introductory sessions with a psychiatrist and a psychiatric nurse. Then, all patients went through an all-day experimental psychotherapy session after administration of either MDMA or placebo.

During these sessions, subjects sat or reclined on a futon bed with the co-therapists seated in chairs on either side.

“The first dose of MDMA (125 mg) or placebo was given in a capsule by mouth at 10 a.m.,” wrote the researchers. “Subjects then rested in a comfortable position with eyes closed or wearing eyeshades, and listened to a program of music that was initially relaxing and later emotionally evocative.”

Quiet introspection and therapeutic discussion occurred in approximately equal balance, they said.

Afterward, subjects remained overnight at the clinic under the supervision of a nurse.

The researchers adapted a psychotherapy protocol developed by psychiatrist Stanislav Grof, M.D., for use in testing LSD. Grof has done substantial research in the field of psychedelic substances and mental health.

“It's a more spontaneous approach compared to CBT,” said Mithoefer. “We didn't direct the patients to process their trauma exposure, but they usually brought it up.”

The next morning, study participants had another 90-minute session with therapists. This “integration” session was conducted without drugs, as were three weekly follow-up sessions. A second experimental session with the drug four weeks after the first was again followed by four drug-free integration sessions.

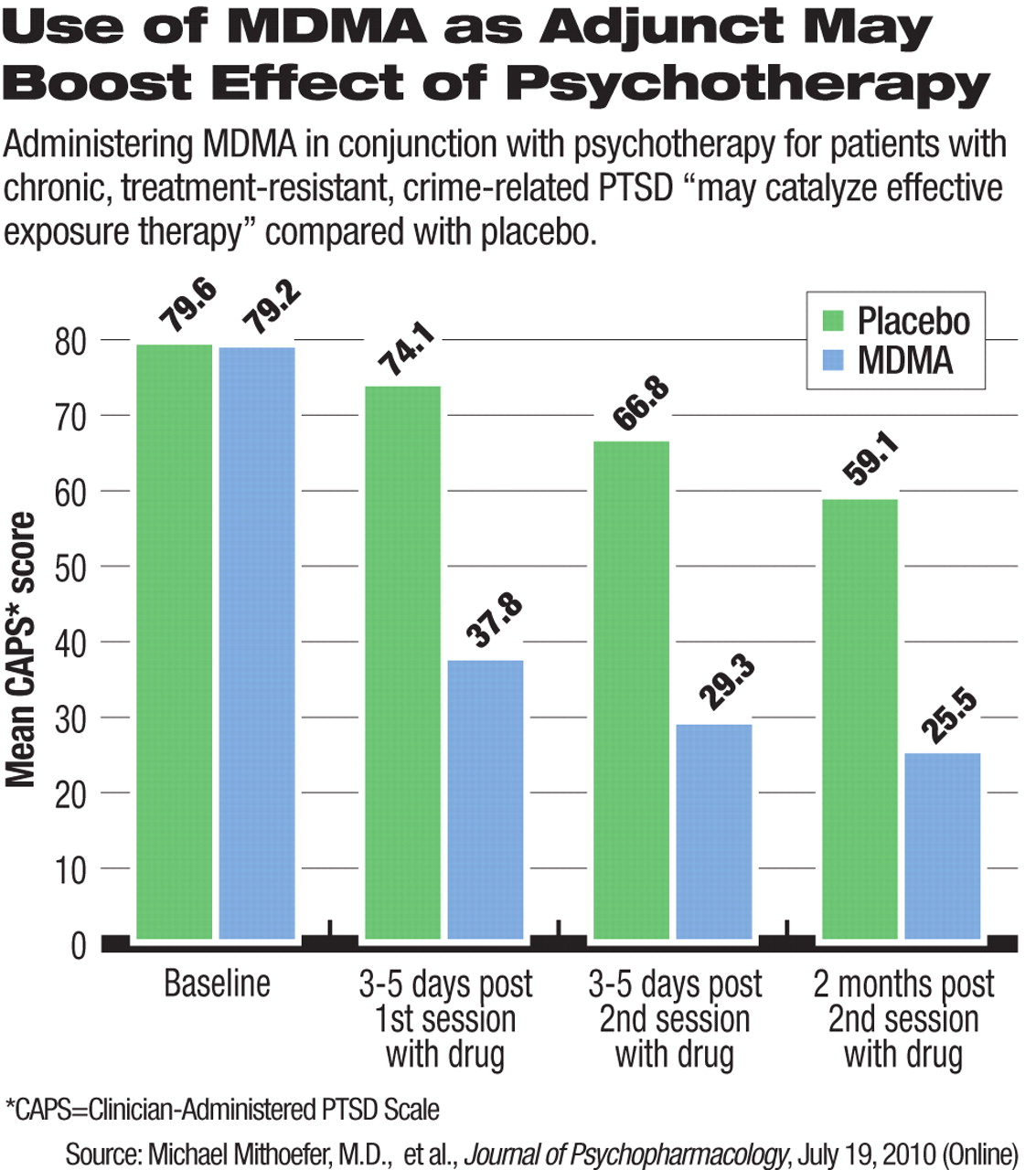

Patients were tested with the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) and the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) at baseline (up to four weeks before the first MDMA session) and again three to five days after each experimental session and two months after the final experimental session.

Majority Showed Symptom Reduction

Clinical response, defined as a greater than 30 percent reduction in CAPS score, occurred in 83 percent of those who took MDMA, compared with 25 percent of those given a placebo.

Patients on placebo in this first stage were given the chance to try MDMA-assisted therapy and seven of eight did so.

Mithoefer is now analyzing the long-term outcomes of this study, although the findings have not yet been published.

“After an average of 3.5 years, some have relapsed, but the majority has not,” he said.

Mechanism of Action Still Unknown

MDMA's mechanism of action is undetermined, though there is speculation that it elevates oxytocin levels. Imaging studies by other researchers indicated that 75 minutes after administration of MDMA, subjects showed less activity in the amygdala and more in the prefrontal cortex, suggesting an improved ability to process trauma-related material.

Mithoefer noted limitations in this trial, in addition to the small number of patients. For example, nine subjects had used MDMA recreationally before the study, which, he said, might introduce some self-selection bias.

Also, the trial design involved more than 30 hours of patient-therapist contact, including the two all-day therapy sessions, he said. “These are not usual features of psychotherapy practice in outpatient settings.”

Blinding was also an issue, since it was easy for subjects and clinicians to tell who had received the study drug and who received the placebo. Mithoefer said he will seek approval for another study, one that uses low, medium, and full doses, hypothesizing that the low dose will give the sensation of taking a real drug without the therapeutic effects provided by the full dose. This next phase 2 trial will include only military veterans.

“The drug is not a magic bullet,” said Mithoefer. “It's the fact that the drug serves as a catalyst in the right setting that's important.”

Further research will be needed to confirm observations by Mithoefer and colleagues. Any clinical use remains on a distant horizon, given safety and legal concerns.

“I'm always in favor of research to cast new light on unexplored areas,” said Kudler. “But most clinicians would be extremely cautious about working with a substance that can cause long-term neurocognitive problems or abuse.”

“The Safety and Efficacy of+/-3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine-Assisted Psychotherapy in Subjects With Chronic, Treatment-Resistant Posttraumatic Stress Disorder” is posted at <www.maps.org/mdma/ptsdpaper.pdf>.