Although obesity and eating-disorders research tend to be separate fields, the two are now converging in an intriguing manner. They're showing that some of the same peptide hormones are involved in both conditions.

The hormones, discovered about 15 years ago, are leptin, ghrelin, and the endocannabinoids. They have a substantial impact on people's appetite, energy metabolism, and food intake. All act on the hypothalamus. Leptin decreases food intake; ghrelin and the endocannabinoids increase it (see

Peptides May Be Treatment Targets).

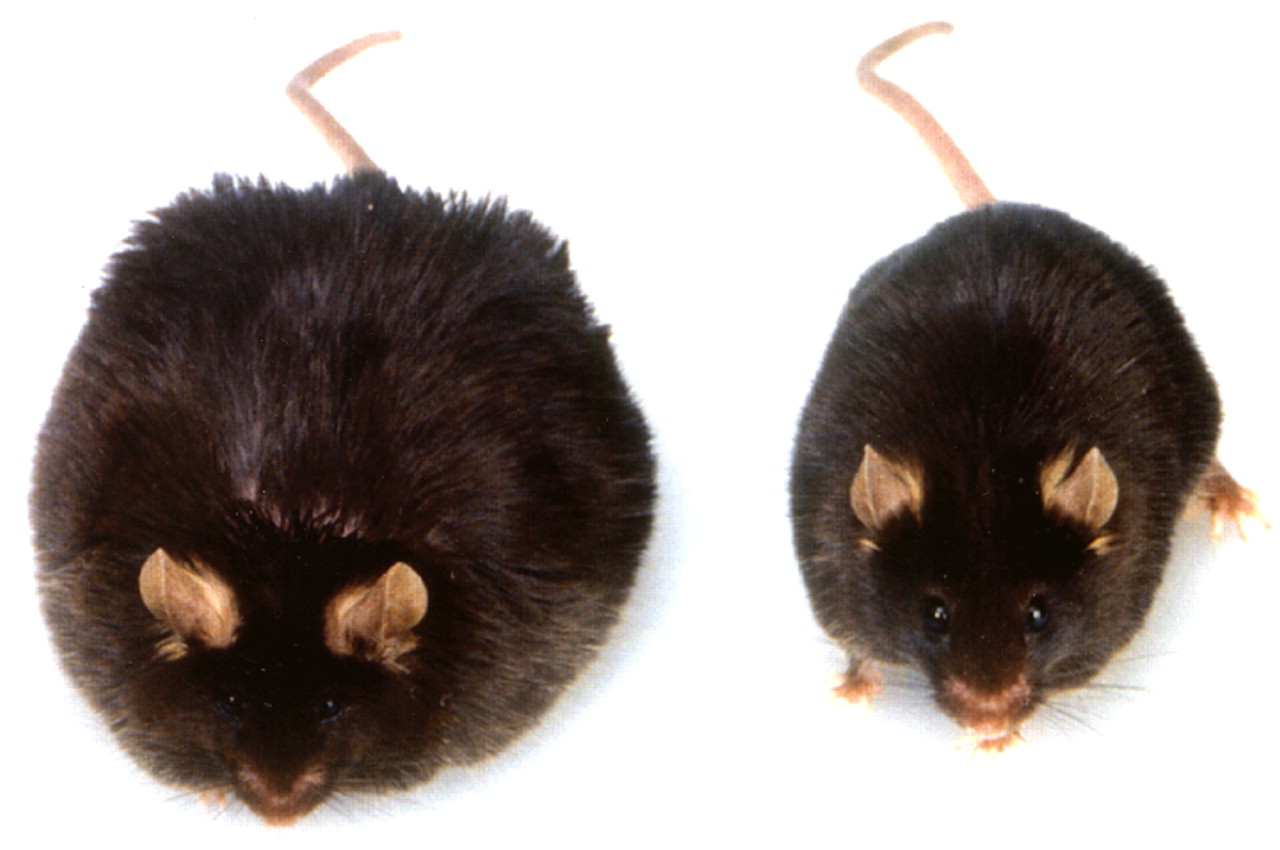

Obese people have been found to have an abnormally high level of leptin in their bloodstream. They are resistant to the effects of leptin in much the same way that people with type 2 diabetes are resistant to the effects of insulin. Individuals with anorexia nervosa or with bulimia nervosa have been found to have abnormally low concentrations in their bloodstream.

Ghrelin levels have been found to be abnormally high in the bloodstream of individuals with anorexia; they have been found to be abnormally low in the bloodstream of individuals with bulimia or binge-eating disorder.

Biology Can Trump Willpower

Such discoveries have some important implications, Walter Kaye, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and an anorexia researcher, explained during a recent interview. “They demonstrate that there is powerful biology underlying obesity and eating disorders, that it's not just a matter of willpower.”

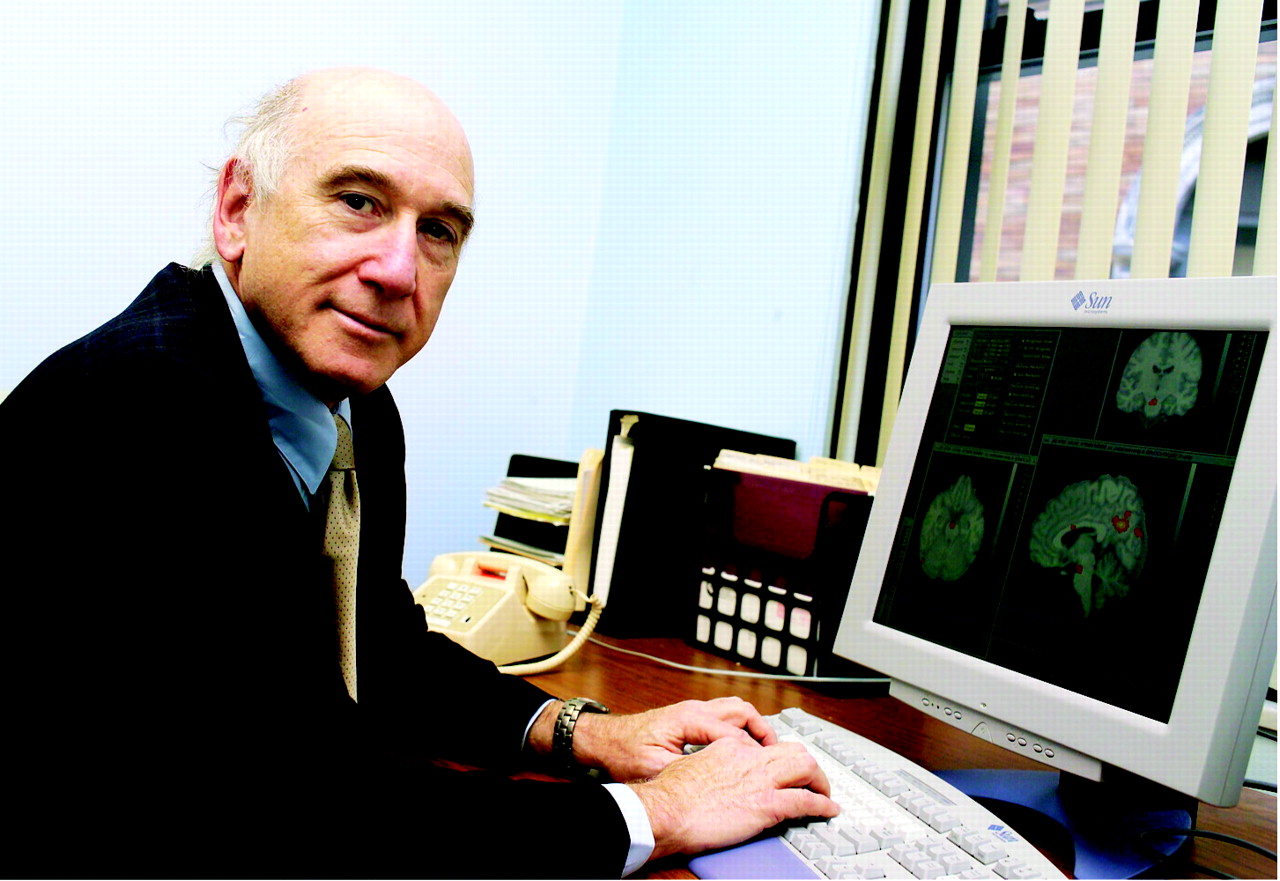

Michael Schwartz, M.D., a professor of medicine at the University of Washington and an obesity researcher, agreed:

“Most people had argued that obesity is a disorder primarily of willpower. These data suggest that there is an underlying biological problem directly involved in obesity.”

But at the same time, it's not just these hormones that dictate food consumption in obesity and eating disorders, scientists are finding. The brain does too.

For instance, Kaye found that when subjects with anorexia and healthy control subjects were offered a tasty treat, the insula—a brain region that processes gestation and links it to reward—responded less in the anorexia subjects than in the controls.

Cary Savage, Ph.D., an obesity researcher at the University of Kansas, showed pictures of snacks to obese and healthy-weight subjects. The anterior cingulate cortex was activated considerably more in the former than in the latter. This brain region has also been implicated in activities other than eating that some people may find rewarding—alcohol dependence, cocaine dependence, and pathological gambling. “These findings of increased activity in reward centers of the brain are consistent with other data indicating that obese individuals make food choices and consume more based on the hedonic aspects of eating,” Savage told Psychiatric News.

Several neuroimaging studies have also demonstrated abnormal activation of the anterior cingulate cortex in subjects with bulimia.

Yet Many Questions Remain

Yet many questions about the roles of leptin, ghrelin, and the endocannabinoids in obesity and eating disorders press for answers. For example, leptin is reduced in people with anorexia as long as they are malnourished, but the levels rise as they recover from their illness. Does this finding mean that leptin levels do not contribute to anorexia, but result from malnutrition? Several variants in the ghrelin gene have been linked with binge-eating disorder. Does this finding mean that the gene variants promote binge eating? Researchers said that it is unlikely that binge eating would lead to the gene variants.

Regardless of whether these hormones contribute to obesity and eating disorders or are affected by them, do they act alone or in concert? The situation is more complicated than scientists originally thought, Rene Klinkby Stoving, M.D., Ph.D., told Psychiatric News. He is an associate professor of endocrinology at Odense University in Denmark and has studied these hormones and their functions.

Kaye concurred with that observation, explaining that “there are a number of different neuropeptides, not just leptin, ghrelin, and the endocannabinoids, that signal something about energy metabolism in the body to the brain. Furthermore, they seem to interact with each other and even show some redundancy. That is, there are many energy signals, and maybe you can affect one of them, but then others seem to take up the slack.”

And once leptin, ghrelin, or the endocannabinoids signal the hypothalamus, what happens then? Is that the point where higher-order areas of the brain ignore the hormones' signals and nudge a person into overeating or undereating? Very possibly. Or perhaps the nudging comes later. In any event, it is the brain, not the hormones, that influence the overeating or under-eating decisions.

For as Schwartz explained, “The system that leptin, ghrelin, and the endocannabinoids are acting on is designed to promote stability in body mass. But sometimes an emotional or psychiatric problem can be so severe as to override the ability of that homeostatic system to compensate. One example in my view is anorexia nervosa. It overwhelms the normal response to weight loss. If healthy people lost as much weight as is typical in a patient with anorexia nervosa, you would have changes in leptin and ghrelin that would potentially activate the drive to eat and induce other metabolic responses that favor the recovery of lost weight.”

“Circuits that play a key role in reward or pleasure in the brain may be where the pathology in anorexia and bulimia, and in obesity, ultimately lies,” Kaye speculated.