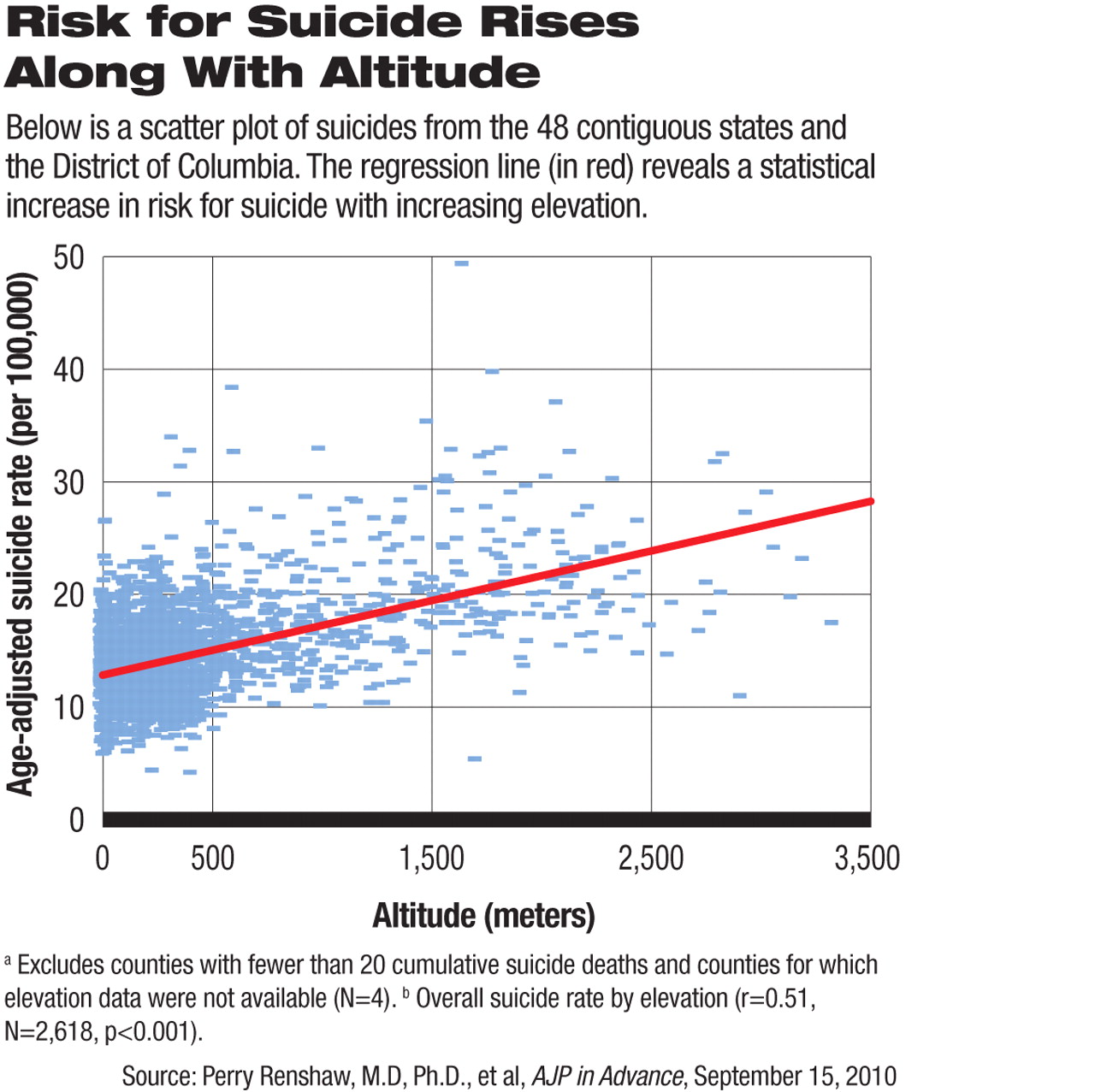

Living at high altitude might be a contributing factor in some suicides.

That's the surprising finding from a study evaluating the relationship between average county and state altitude in the United States and total age-adjusted suicide rates, firearm-related suicide rates, and nonfirearm-related suicide rates.

The association may be related to the effects of metabolic stress associated with mild hypoxia in individuals with mood disorders, say lead author Perry Renshaw, M.D, Ph.D., and colleagues.

The study appeared online in AJP in Advance September 15.

The study replicated the known association between levels of gun ownership and suicide, but the correlation between altitude and suicide was significant for both firearm and nonfirearm-related suicide, and statistical analysis showed that elevation had a more significant association with age-adjusted suicide rates than did gun ownership.

Moreover, regression analysis assessing suicide and altitude in the context of a number of potential confounding variables—available medical and mental health care in the area (including number of psychiatrists), poverty, unemployment, lack of education, population density, male and female population ratios, and divorce—revealed that altitude continued to be significantly independently associated with suicide.

“It raises the $64-million-dollar question: why is this happening?” Renshaw told Psychiatric News. “There are groups of people who are at increased risk of suicide, and something about living at higher altitude seems to be tremendously increasing the risk.”

Renshaw is an investigator at the Brain Institute of the University of Utah and the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center at Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

In the study, elevation data were calculated from datasets compiled from the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Suicide and population density data were obtained through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) WONDER database. Gun ownership data were obtained through the CDC's Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Remarkably, a secondary analysis to determine the possible effect of cultural factors by examining the same correlations in South Korea produced similar findings—altitude appears to be independently associated with suicide. (South Korea was selected because it is culturally quite different from the United States, has a variable geography with many mountainous areas, and has a relatively high suicide rate.)

Renshaw cautioned against simplistic interpretations: suicide is a rare event, and surveys have consistently shown that satisfaction with quality of life in Rocky Mountain areas is high.

Rather, Renshaw said that he believes high altitude may be associated with metabolic changes in at-risk individuals—those with existing psychiatric disorder and/or substance abuse—that may increase their risk for suicide.

Anecdotally, individuals who visit Rocky Mountain areas sometimes report transient symptoms of depression. And those with bipolar disorder have been known to experience a recurrence of symptoms after moving to mountainous regions, he said.

Prior to Renshaw's coming to the University of Utah, much of his research while director of the McLean Hospital Brain Imaging Center in Belmont, Mass., focused on in vivo neurochemical changes associated with mood and drug abuse disorders.

The findings on altitude and suicide point the way to future research looking at such changes in at-risk individuals living in high-altitude areas. “We will have a lot more information over the coming years, and we hope we can identify chemical changes that occur at increased altitude,” he said. “This will create the opportunity for novel therapies for individuals already struggling with psychiatric disorders and substance abuse.”