In March 1971, a French human-rights organization released to the Western press 150 pages of documents said to be the photocopied forensic reports on six citizens of the Soviet Union being held involuntarily in psychiatric hospitals.

Accompanying the documents was a letter addressed to Western psychiatrists. As reported by Peter Reddaway and Sidney Bloch, M.D., in their 1978 book, Psychiatric Terror, the letter read, in part: “In recent years in our country a number of court orders have been made involving the placing in psychiatric hospitals ... of people who in the opinion of their friends and relatives are mentally healthy.”

The letter noted that the six individuals were “well known for their initiatives in defense of civil rights in the Soviet Union” and contained a specific request to psychiatrists: Did the forensic reports describe evidence of mental illness sufficient to warrant incarceration?

The letter was signed by Vladimir Bukovsky, a biophysicist and human-rights activist who had himself been incarcerated; the documents were compiled by a small group of underground activists in Moscow. It was a dramatic breakthrough and one of the first glimpses the Western world had of a fledgling human-rights movement that had begun to emerge in the Soviet Union, including a group who formed the Working Commission to Investigate the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes.

Reddaway, at the time a political science professor at the London School of Economics, recalled that the dissidents in Moscow in the early 1960s had adopted the tactic of taking Soviet law at face value to protect their right to protest.

“They would point out that they were only exercising the rights afforded under the Soviet constitution,” he told Psychiatric News. “It sounds simple, but in many cases it worked because the authorities were not sure how to handle the dissident movement.

“One of the responses the authorities developed was to argue that because there could be no flaws in a socialist society, the only explanation for the dissidents' behavior was a distorted view of reality,” Reddaway said. “On a small scale at first, but increasingly throughout the 1960s and 1970s, they began to put the early Soviet dissidents into psychiatric hospitals. Sometimes they did this through administrative means without a trial, placing individuals in mental hospitals, and in other instances [the dissidents] had a trial in which they were examined by a psychiatrist who would do what the authorities demanded.”

The World Is Watching

The “Bukovsky papers” were among the first substantiated evidence of the practice of using psychiatric incarceration to detain political dissidents—a practice that, as recorded by Reddaway, was used sporadically as early as the Stalin period, but in time became a systematic response to political dissent. And it was a practice that would eventually arouse Western psychiatric opinion and lead to a confrontation between APA—and other Western psychiatric organizations—and the Soviet All-Union Society of Psychiatrists and Neuropathologists.

The confrontation resulted in a statement by the World Psychiatric Association in 1977 denouncing political abuse of the profession and later in the withdrawal of the All-Union Society from the world body under threat of expulsion (see

Soviets Left WPA Under Expulsion Threat). In 1989 the face-off culminated in a remarkable visit by American psychiatrists led by the U.S. State Department in which the American delegation interviewed individuals believed to be incarcerated in psychiatric hospitals due to political activity.

But movement by Western psychiatry was hesitant at first, and Reddaway and others acquainted with the period described a fitful process—a slow accretion of evidence, the surreptitious establishment of a network of contacts within and outside of the Soviet Union, widening publicity for the dissidents' cause and about the nature of psychiatric abuse, and only later the mobilization of professional and organizational protest.

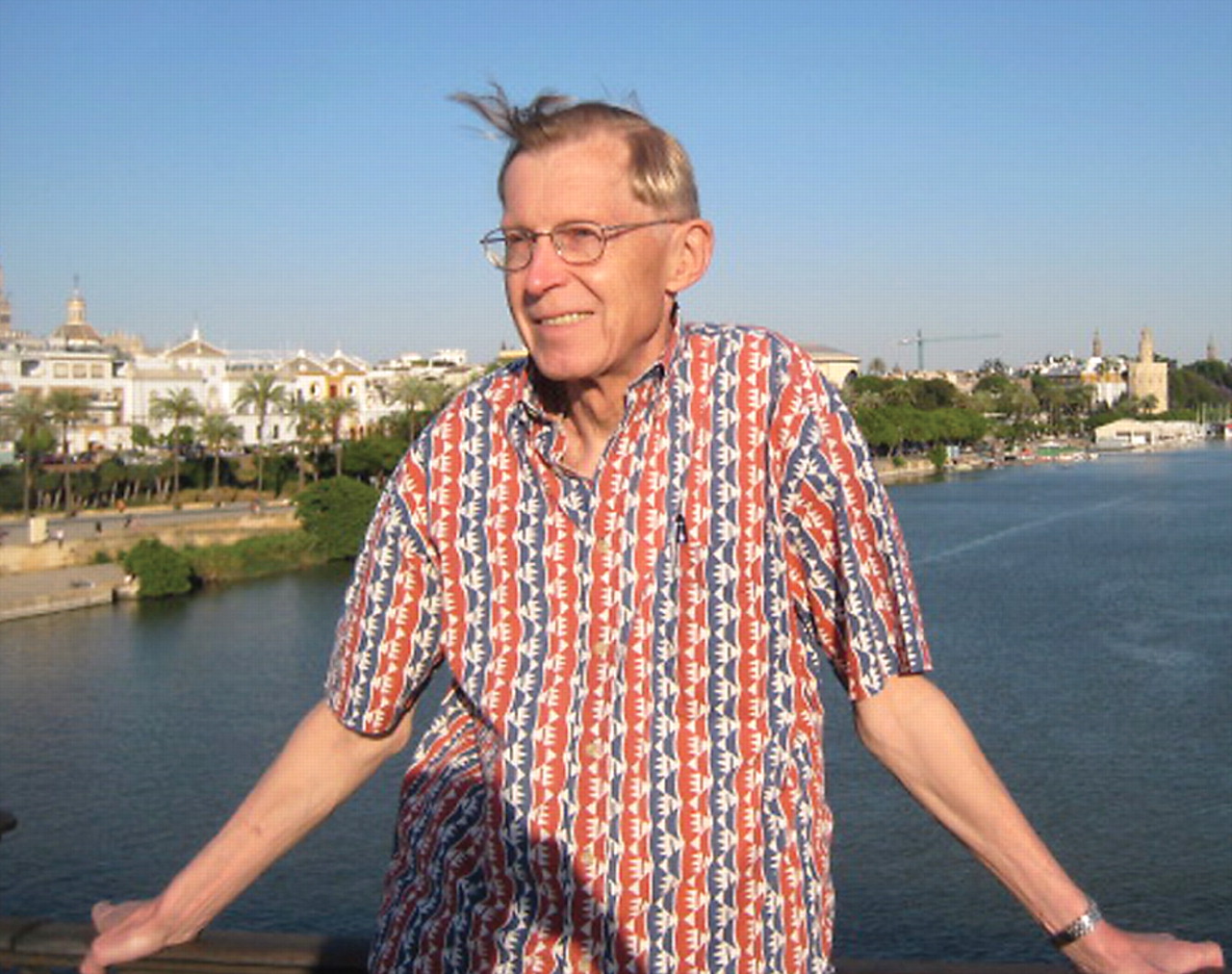

This epic story is told in a new book, Cold War in Psychiatry: Human Factors, Secret Actors, published this year by Dutch human-rights activist Robert van Voren, and in two volumes by Reddaway and British psychiatrist Sidney Bloch, M.D. (The first, Psychiatric Terror, earned Reddaway and Bloch APA's Manfred S. Guttmacher Award in 1978. Their second book, Soviet Psychiatric Abuse: The Shadow Over World Psychiatry, was published in 1985.)

APA Gets Involved

At APA, a crucial development was the arrival of Melvin Sabshin, M.D., as medical director in 1974. Sabshin brought with him an international perspective and a commitment to the development in the United States of a more rigorously scientific psychiatric nosology—as opposed to ideological or theoretical approaches—that made effective confrontation with the Soviets possible (Psychiatric News, November 5).

During Sabshin's tenure, APA's Board of Trustees, with the strong recommendation of the Council on International Affairs, established the Committee on International Abuse of Psychiatry. Sabshin hired world traveler Ellen Mercer, who served as staff liaison to the committee and later as director of APA's Office of International Affairs when it was formed in 1982.

Reddaway was appointed a consultant to the committee and van Voren served informally as an advisor to Mercer (van Voren had befriended Bukovsky after the latter was released from the Soviet Union in an exchange for Chilean communist leader Luis Corvalan in December 1976). With the help of Reddaway and van Voren's contacts in the Soviet dissident community, the committee began to make contact with incarcerated individuals, their family members, and official Soviet psychiatry.

The strategy was straightforward and modeled on the practice of Amnesty International: the committee wrote letters.

“Cases would come to us through various channels but mostly from the Moscow Working Commission,” Mercer recalled in an interview with Psychiatric News. “We would send letters to the prisoners, their families, and to the institutions where they were incarcerated. We didn't always have their family members' contact information, but we would write to them if we did.

“The content of the letters was less important than the fact that they were on APA letterhead and had the name of the individual in the letter,” she said. “We would always say something like, ‘It has come to our attention that _____ has been incarcerated in ________________ hospital allegedly for nonmedical reasons. We would appreciate your sharing with us the reason the person is there and whatever other information is available.’”

Incarcerated individuals were not always strictly political dissidents protesting human-rights abuses, but included members of disparate national groups seeking independence, as well as members of religious sects, including the Russian Orthodox Church and Protestant denominations, and Jews seeking to emigrate to Israel or the West.

Some of the cases also involved psychiatrists who refused to cooperate with KGB authorities in detaining individuals. Among these were two—Semyon Gluzman, M.D., and Anatoly Koryagin, M.D.—on whose behalf APA was vocal. Gluzman had early on protested the incarceration of Pytor Grigorenko, a Soviet World War II hero, and earned for his courage seven years in a forced-labor camp and three years in exile. Gluzman was later made a distinguished life fellow of APA, and in 1982 he returned to Kiev and later became a leader of Ukrainian psychiatry.

Koryagin was a consultant to the Moscow Working Commission to Investigate the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes and wrote an article in the April 11, 1981, The Lancet titled “Unwilling Prisoners.” A footnote to that article stated that earlier that same year, Koryagin had been arrested and charged with “anti-Soviet agitation.” After serving time in prison, he was exiled to Switzerland and later returned to the Soviet Union.

APA's letters rarely, if ever, received a response, but the communication served notice to Soviet officialdom that the world was watching.

And it had an effect. Mercer recalled that in a meeting with dissidents at the American Embassy in Moscow in 1989, prior to the visit of American psychiatrists led by the State Department, many stated that the publicity had saved their lives.

“We know from people who were released that they received much better treatment because of the letters than those who did not come to the attention of people and organizations in the West,” Mercer said. “And, usually, they had no idea how and why they were noticed and others were not.”

Reddaway agreed. “The dissidents themselves firmly believed the more foreign pressure the better, and if someone was released, they all felt the pressure had played an important part,” he said. “I have studied official documents in the Soviet archives, including minutes from meetings of the Politburo, and it is obvious that Soviet authorities at high levels paid close attention to foreign responses to these cases.”

In the third article of this series, Psychiatric News will look back on the 1989 visit of American psychiatrists to the Soviet Union.