A 10-year follow-up study of boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) finds that the disorder persisted into their early adult years in 3 out of 4 of the subjects, leaving them vulnerable to poor psychiatric outcomes and life prospects, said Joseph Biederman, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital.

Long-term outcome data in those with ADHD are hard to come by, he said at the APA Institute on Psychiatric Services in Boston in October.

Not only can ADHD research be quite expensive and difficult to carry out, he explained, but also selection criteria, duration of follow-up, and age at follow-up can vary from study to study, making it difficult to compare study populations.

Definitions of persistence and remission in ADHD studies can also be problematic, said Biederman. A patient who loses just one symptom and thus falls below full diagnostic status may be considered in “syndromic” remission. Some researchers may use “symptomatic” remission, the loss of 50 percent of symptoms. Others may use “functional” remission, a status that indicates no symptoms and no impairment.

“Depending on the definition used, 10 percent to 70 percent of your sample achieves remission,” said Biederman.

Long-term studies would help clarify the course of the disorder and link the pediatric and the adult literature on illness and treatment, he noted.

At the institute, Biederman reported on long-term outcomes in 110 boys with ADHD and 105 without.

The boys were aged 6 to 17 when they were first diagnosed with ADHD. The results of the 10-year follow-up of these subjects thus overlapped with retrospective data from studies of adult cohorts.

Biederman and colleagues defined remission using full DSM-IV criteria. By that standard, 65 percent of the patients could be said to be in remission at the 10-year follow-up because they did not meet the full diagnostic criteria.

However, from another perspective, only a minority of these youngsters achieved complete remission. About 78 percent had some form of persistent ADHD—about 35 percent had full persistence of the disorder, and 43 percent had partial persistence. Of that 43 percent, 22 percent had subsyndromal ADHD, 15 percent had impaired functioning, and 6 percent were in remission and still being treated.

Persistence of the ADHD correlated with having more psychiatric comorbidities, including, in particular, oppositional-defiant disorder, conduct disorder, anxiety, and use of psychoactive substances.

Those children with persistent ADHD also tended to do worse in school: repeating grades, needing special classes, getting suspended, and having lower high-school graduation rates than controls.

“The majority continued to struggle into their adult years,” said Beiderman. “Poor educational outcomes lead to poor job prospects and worse overall long-term outcomes in life.”

Thus it is crucial to address ADHD aggressively in childhood and monitor children with the disorder for residual manifestations of the disorder and comorbid disorders, he said.

“Loss of a symptom should not be confused with recovery,” he emphasized.

On the same program, Carter Petty, M.A., of the biostatistical unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, reported on 11-year outcomes of ADHD in girls.

Girls are an understudied population, said Petty. For every girl in clinical populations with ADHD, there are nine boys. Girls are referred to clinics at half the rate boys are, possibly because they display fewer comorbid disruptive behaviors, he suggested.

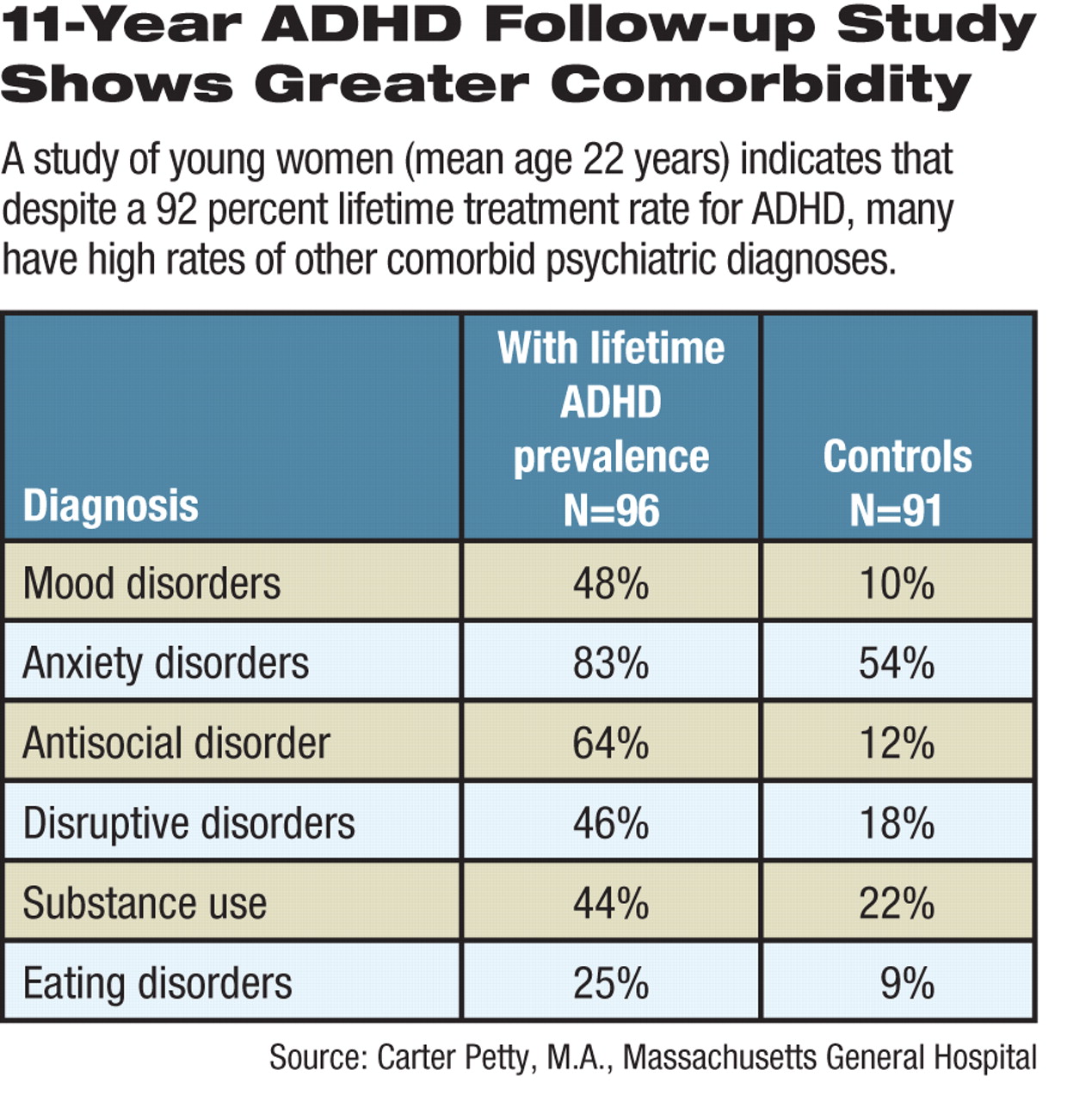

For this study, Petty compared 96 girls who had ADHD with 91 girls who did not. Their median age at follow-up was 22. About 92 percent of subjects had been treated with medications, and 42 percent took medications in the year prior to the start of the study.

“ADHD in girls is associated with higher lifetime and current comorbidity with a wide-ranging list of psychiatric disorders,” he pointed out.

Lifetime and prior-year rates of mood, anxiety, antisocial, disruptive, and substance use disorders were higher in girls with ADHD than the controls (see table).

“This indicates risks similar to those for boys, suggesting that A DHD is expressed similarly in both genders,” said Petty. “The rates are also similar to rates for adults with ADHD, giving further support for the continuity of ADHD from childhood to adulthood.”