Canadians who need either urgent or nonemergency treatment for mental illness continue to face long waits for care, although in 2009 the delays slightly decreased from previous years.

According to recent research from the Fraser Institute, a Canadian free-market-oriented research organization, psychiatrists reported that their patients faced median nationwide waits of 16.8 weeks from the time they were referred by a primary care physician to the beginning of treatment. That time is a slight decrease over the 18.6-week median national wait time for psychiatric care found in 2008 and the shortest since the Fraser researchers began annually measuring psychiatric wait times in 2003.

The findings were based on estimates derived from responses by psychiatrists to the survey. About 11 percent of Canadian psychiatrists, or 458, responded to the survey. The survey did not ask whether they were accepting new patients.

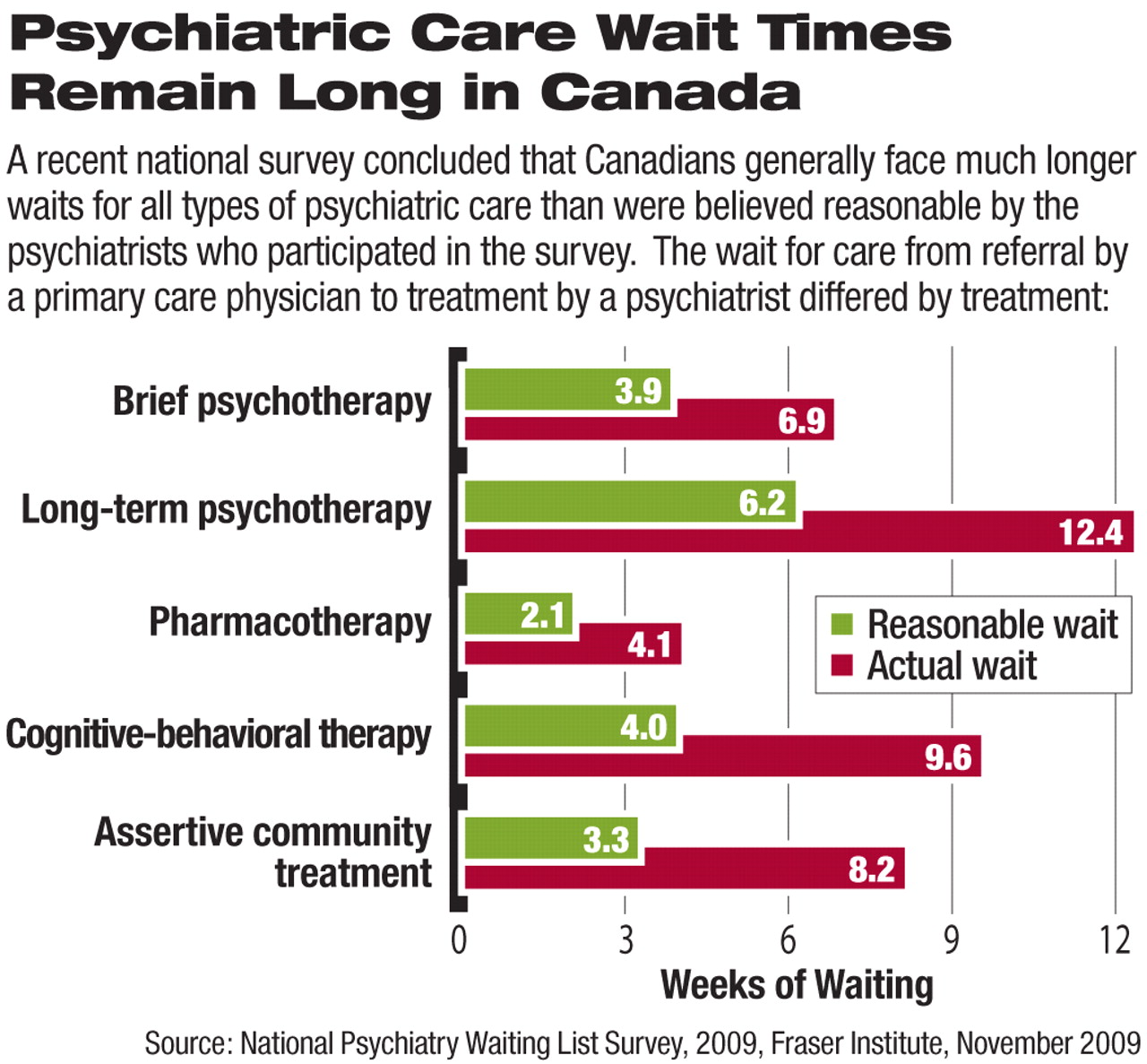

The wait times identified were significantly longer than the “clinically reasonable” delays suggested by the same psychiatrist respondents. The mean national wait time for all treatments was nearly 150 percent longer than what psychiatrists thought was clinically acceptable.

“And those are not necessarily ‘reasonable’ wait times from the perspective of patients with these illnesses who are waiting for care,” said Nadeem Esmail, director of Health System Performance Studies at Fraser and author of the report, in an interview with Psychiatric News.

The wait times found by Fraser are likely underestimates, according to Canadian psychiatrist Jack Brandes, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto. He told Psychiatric News that analyses of patient waits for psychiatric care—like statistics on unemployment—do not include people who have given up seeking psychiatric care.

The experience of Brandes and other psychiatrists he knows indicates that it is very difficult to find physicians who accept patient referrals with less than a several months' wait.

The survey findings also reflect other research on psychiatric wait times in Canada. The Fraser survey found that the waiting period to see a psychiatrist once the general practitioner made a referral was seven weeks for nonemergency symptoms. Similarly, a 2009 study performed for the Wait Time Alliance by the Canadian Psychiatric Association (CPA) found a median wait time of 5.7 weeks nationwide for patients for nonemergency treatment of major depression. That wait is beyond the CPA's recommended four-week wait time to see a psychiatrist for such a condition.

“What [both findings] say overall is that people are waiting too long,” said Susan Abbey, M.D., former president of the CPA and an author of the CPA study, in an interview.

The CPA-identified delays in care also are likely underestimates, Abbey said, because they don't account for the fact that nearly one-third of Canadian psychiatrists do not accept new patients, and that likely further complicates patients' search for psychiatric care.

The findings come several years after Canada's central government launched a multibillion dollar effort to cut wait times in several nonpsychiatric areas of medicine. The psychiatric wait times—longer than nonpsychiatric care wait times, according to Fraser—demonstrate the need for government resources to focus on cutting wait times in this area, Abbey said.

For instance, Fraser found that in 2009 the total wait time between referral from a primary care physician and treatment averaged 16.1 weeks across 12 specialties, compared with 16.8 in psychiatry.

“Unfortunately, there is no magic-bullet fix,” she said.

Steps that could reduce delays in obtaining psychiatric care, Abbey said, include an increased number of medical school slots with the hope that more of these students would enter psychiatry and increased government encouragement of clinician care coordination.

Alternately, Esmail concluded that wait times would be cut if Canadian governments that operate the government-controlled universal health care system allowed more psychiatrists to operate in private capacities and if patients shared some of the cost of their care. A private system would remove some patients from the public system, reducing demand there.

Brandes agreed with some of the free-market suggestions, noting that it might be possible to get the existing psychiatrists to work more hours and treat more patients if they could charge more per hour in a private system.

Esmail noted that other universal health care systems, such as Australia's, have no such waiting lists because they allow private-sector alternatives to public health systems.

After an extensive search, Psychiatric News could find no publicly available national psychiatric care wait time estimates for U.S. patients in any of the major public or private health care systems, although many individual psychiatrists report waits that are often lengthy. For example, in the Texas Medicaid program, “wait times of several weeks to see a psychiatrist are common,” according to a 2005 study by the Center for Public Policy Priorities.