The science of mental illness prevention is coming of age, a spate of recent studies has demonstrated (Psychiatric News, January 2, 2009; August 7, 2009; January 1).

And here's one more study underscoring the trend—it found that cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can prevent depression in some adults who are highly susceptible to it.

The lead investigator was Claudi Bockting, Ph.D., an associate professor of clinical psychology at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. The results appeared in the December 2009 Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

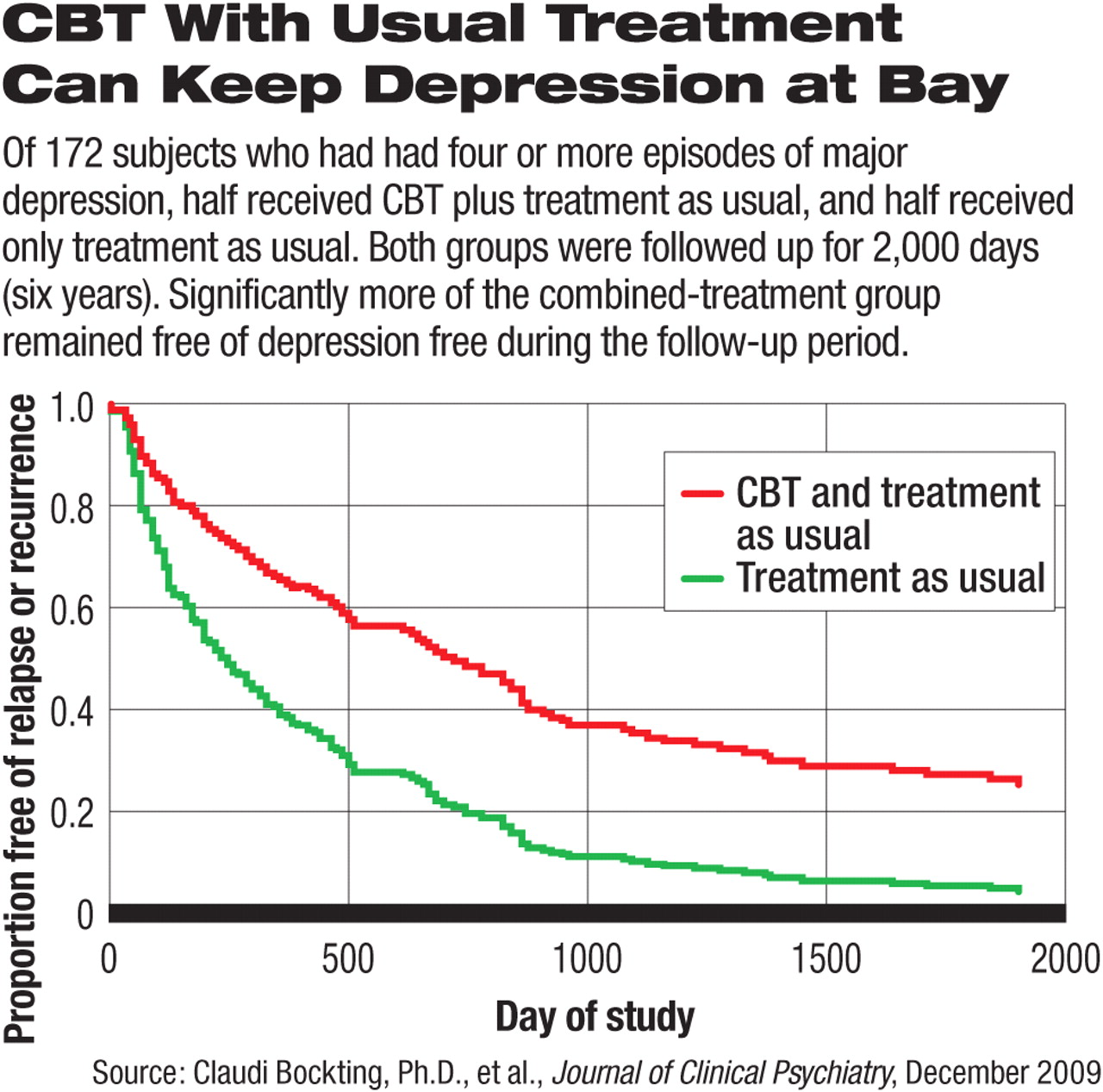

The study included 172 subjects who were in remission from major depression and who had experienced at least one other episode of major depression during the previous five years. In fact, over half the sample had had four or more episodes of major depression within that time span.

Half the subjects were assigned to treatment as usual and half to an eight-session group CBT intervention plus treatment as usual. The CBT intervention was focused mainly on identifying and changing dysfunctional attitudes, enhancing specific memories of positive experiences by having subjects keep a diary of positive experiences, and formulating specific relapse/recurrence prevention strategies. All subjects were followed for six years on average.

The CBT intervention was not found to provide a significant protective effect against further major depressive episodes in subjects who had had two or three major depressive episodes, but it was found to do so in subjects who had had four or more.

More specifically, 41 subjects who had experienced four or more episodes of major depression received treatment as usual, whereas 49 subjects who had experienced four or more episodes of major depression received CBT plus treatment as usual. During the six-year follow-up, 95 percent of the former group experienced at least one more depressive episode, compared with only 75 percent of the latter group—a significant difference.

Why did CBT seem to protect quite a number of individuals who had had four or more depressive episodes, but not those who had had only two or three of them? A possible explanation, the researchers speculated, could be that the former became depressed through rumination and unhealthy thinking patterns—types of thinking that CBT could correct—whereas the latter became depressed in reaction to adverse life events.

In any event, it looks as if CBT has a preventive effect in some people whose thought patterns make them susceptible to depression, and that this effect can endure at least six years after CBT has been completed. Bockting did not expect its protective effects to last so long, she told Psychiatric News.

The implication for psychiatrists, Bockting believes, is that psychiatrists should consider offering CBT to patients who have experienced multiple bouts of depression. The CBT might possibly be their ticket to a depression-free future.

The study was funded by the Health Research Development Council and the National Foundation for Mental Health in the Netherlands.

An abstract of “Long-Term Effects of Preventive Cognitive Therapy in Recurrent Depression: a 5.5-Year Follow-Up Study” can be accessed at <www.psychiatrist.com> by clicking on “The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry,” “Archives,” and the December 2009 issue.