One in eight children aged 8 to 15 experienced some mental disorder in the previous 12 months, but only half of them got any treatment, according to the first national study of childhood prevalence rates conducted in the United States.

The study is based on data collected from 2001 to 2004 as part of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

“There have been regional studies from upstate New York, Oregon, Texas, and western North Carolina but no nationally representative sample to determine the magnitude of the problems [in this age group],” said lead author Kathleen Merikangas, Ph.D., a senior investigator and chief of the Genetic Epidemiology Research Branch at the National Institute of Mental Health.

The NHANES survey interviewed 3,024 children and their parents, but not their teachers or physicians. Interviewers used the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) and DSM-IV criteria.

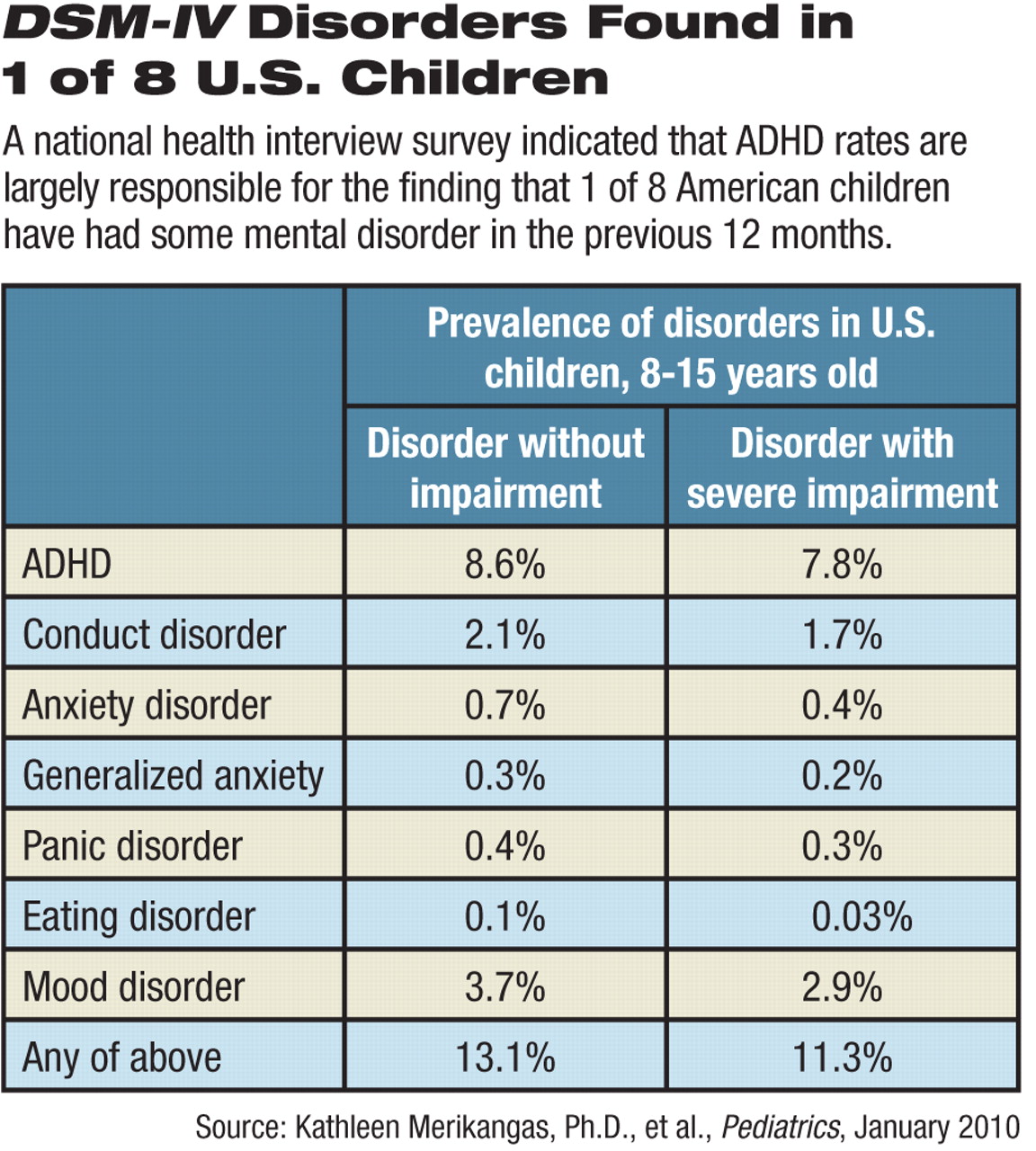

The 12-month prevalence rates were largely driven by attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) at 8.6 percent. In addition, the children surveyed had rates of 3.7 percent for mood disorders, 2.1 percent for conduct disorder, 0.7 percent for panic or generalized anxiety disorder, and 0.1 percent for eating disorders.

Only 1.8 percent of the children had comorbid mental health disorders, a finding probably due to the “limited number of disorders assessed in the current study, compared with the full range of disorders assessed in other studies,” wrote the authors.

Adjusting for severe impairment reduced those rates only slightly.

Boys had twice the rate of ADHD as girls, and girls had twice the rate of mood disorders as boys.

An unusual finding was that Mexican-American children had significantly higher rates of mood disorders than white or black children, contrary to most previous research. Merikangas said that further analysis may clarify whether this result is associated with economic or immigration status or some other factor.

There are some limitations to the study, however, said Mina Dulcan, M.D., head of child and adolescent psychiatry at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine and Children's Memorial Hospital in Chicago. For one, the age range, 8 to 15, may have resulted in missing some cases of disorders (like bulimia or anorexia) for which rates might be expected to be higher in the later teenage years.

Also, the study necessarily under-counted rates of “any disorder” since it did not register substance abuse, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, autism, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and other diagnoses, Dulcan told Psychiatric News.

Only half of these children received mental health services in the prior year, however. That may be an underestimate because children younger and older than the survey's age range have more trouble gaining access to care, said Dulcan.

Treatment rates recorded in the survey were highest for the children with ADHD (47.7 percent) and conduct disorder (46.4 percent) and lowest for those with general anxiety disorder or panic disorder (32.2 percent).

Those disparities may reflect externalizing versus internalizing symptoms, said Merikangas in an interview.

“Anxiety is least recognized in kids, especially by teachers,” she said. “But children with ADHD or conduct disorder are likely to cause trouble for the people around them.”

This and other studies indicate wide variations from state to state across the United States in who and how many children receive treatment, she said.

Patients in treatment thus represent an atypical sample, she said. “We wanted to know what the signs of mental illness are in the general population.”

Merikangas cautioned that the NHANES survey can provide only a ballpark sense of the occurrence of these disorders, since it covered only the prior year and wasn't designed to project lifetime rates. The next task for epidemiologists is to look at lifetime disorder rates and a wider range of disorders, she said.

“The new study adds some data on which to base policy,” said Dulcan. “It is one more piece of documentation that there is a lot of mental disorder out there and not enough services.”