Suppose you gave omega-3 fatty acids to a patient in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Could the supplement keep the illness from developing further? Quite possibly, a study reported in the February Archives of General Psychiatry suggests.

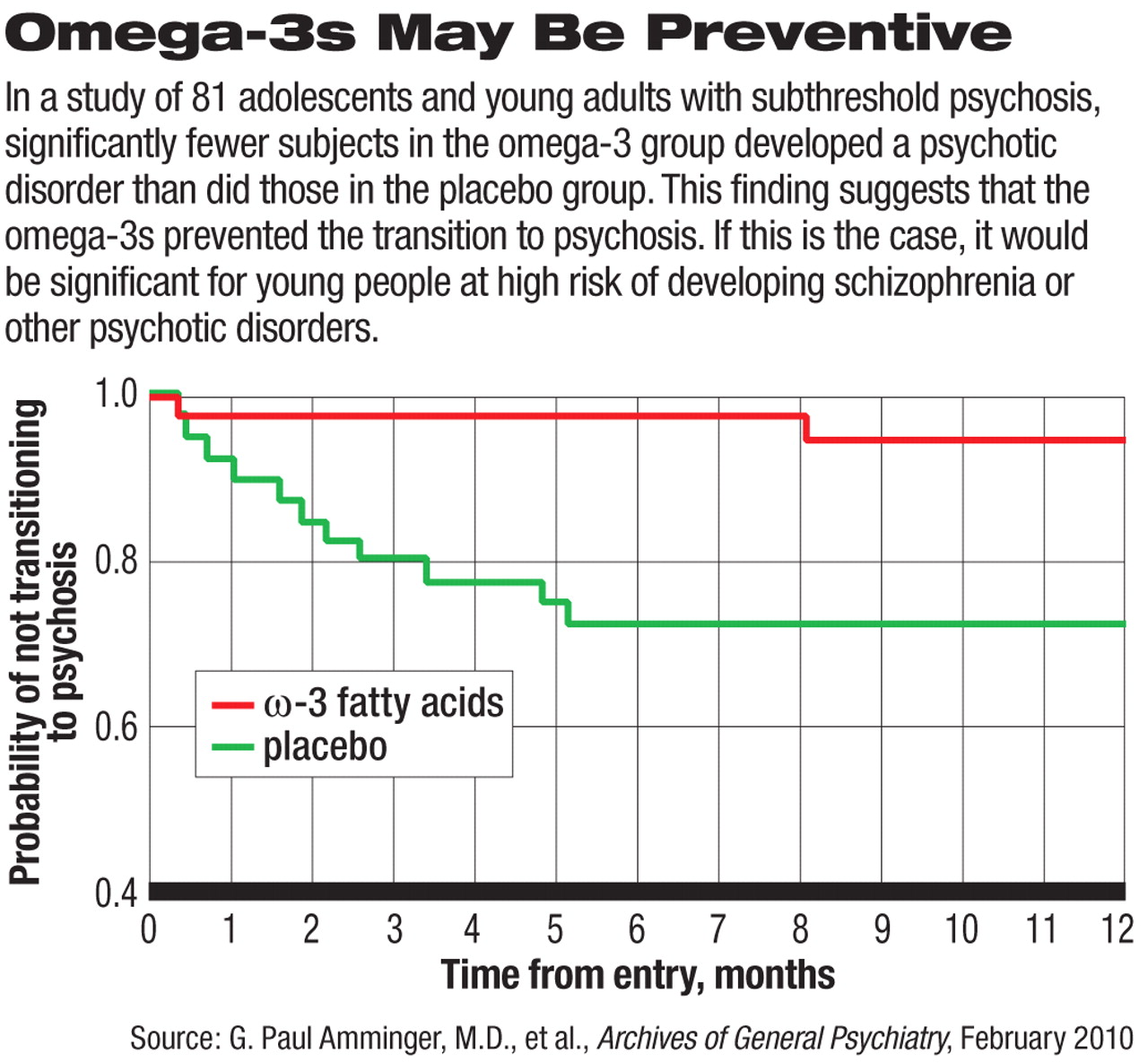

G. Paul Amminger, M.D., a professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the Medical University of Vienna in Austria, and his colleagues gave 81 adolescents or young adults with subthreshold manifestations of psychosis either a supplement of omega-3 fatty acids or a placebo daily for 12 weeks. The daily dose of omega-3 fatty acids used was about 1.2 grams. Subjects were then followed for 40 weeks to determine whether they developed full-blown psychosis. Results for the omega-3 group were compared with those for the placebo group.

Only two of the 41 individuals in the omega-3 group (5 percent), but 11 of 40 in the placebo group (28 percent) transitioned into psychosis, that is, met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar I disorder. This difference was highly significant statistically.

Therefore, the omega-3 fatty acids can “reduce the risk of progression to psychotic disorder and may offer a safe and efficacious strategy for indicated prevention in young people with subthreshold psychotic states,” Amminger and his team concluded.

“I think this is a very important paper,” Scott Woods, M.D., a Yale University professor of psychiatry and one of the scientists trying to keep prodromal schizophrenia from developing into full-blown illness, told Psychiatric News. “Omega-3s are safe, and it would be terrific if they could really prevent psychosis.”

The study, of course, needs replication, he said, “and I have some concerns that the results may not replicate.... Our own experience with a different omega-3 preparation in risk-syndrome patients was so disappointing that we discontinued the study early on.... So the specific preparation may be important, or dose, or perhaps phase-of-illness issues. It may be that the patients we studied were 'later' in the risk syndrome than those studied by Amminger et al.”

Another of his concerns, Woods said, is that the omega-3s, or at least some preparations of them, have a common signature side effect-fishy eructation or "fish burp." As a result, subjects receiving active omega-3s rather than a placebo might realize that they are getting the real thing and thus expect the supplement to help them. Such expectations in turn could skew research results.

Still another weakness of their study, Amminger and his group noted, was that the omega-3s might have simply delayed psychosis, not prevented it. “However, warding off psychosis even in the short term would still be a worthwhile achievement,” they wrote.

How the omega-3 fatty acids might prevent psychosis is not known. Nonetheless, brain scans have shown that they can increase the chemical compound glutathione in the temporal lobes of first-episode psychosis patients, and glutathione is thought to play a critical role in protecting brain cells from oxidative stress.

“We have started a multicenter replication study in which we will recruit 320 young people in eight cities in Europe and Australia,” Amminger told Psychiatric News. “This study, like the previous one, will be supported by the Stanley Medical Research Institute.”