A substantial majority of patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) experience remission of symptoms, and their remission tends to be stable over time compared with other mental disorders—but only half of patients also achieve good social and vocational functioning.

Those were among the findings of a 10-year study of remission and recovery in BPD patients. The study was published online in AJP in Advance on April 15 and will appear in the June print edition of the American Journal of Psychiatry.

“Symptomatically, this is a good prognosis,” said Mary Zanarini, Ed.D., lead author of the study, in an interview with Psychiatric News. “The idea that people with BPD never get better isn't true. But as much as they get better symptomatically, it's clear that we need to pay attention to psychosocial and vocational functioning. Just to talk about symptoms isn't enough.”

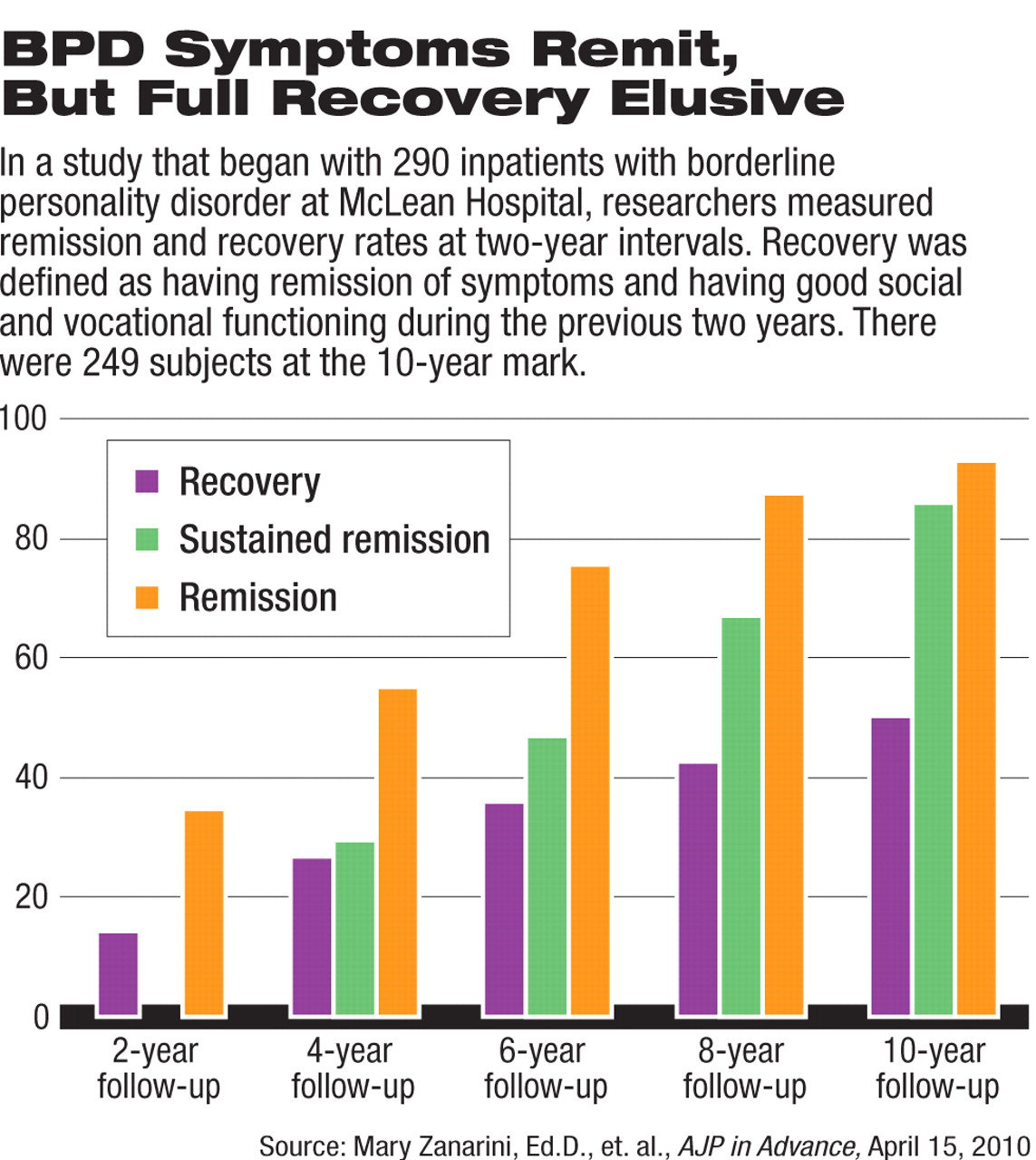

In the study, 290 inpatients at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., who met both DSM-III-R and Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines criteria for BPD were assessed at admission using a series of semi-structured interviews and self-report measures. The same instruments were readministered every two years for 10 years.

At the 10-year mark, 249 patients remained in the study. (Of the 41 patients who were no longer in the study, 12 had committed suicide, seven died of other causes, nine discontinued their participation, and 13 were lost to follow-up.)

Recovery was defined as not only remission of symptoms, but being able to function both socially and vocationally. Social functioning was defined as having at least one emotionally sustainable relationship with a friend, spouse, partner, or other non-blood-related individual. Vocational functioning was defined as the ability to perform full-time work competently and consistently.

Study results showed that 93 percent of the patients achieved remission of symptoms lasting at least two years, and 86 percent achieved remission lasting at least four years. However, only 50 percent achieved the full definition of recovery including social and vocational functioning (see chart).

Zanarini speculated that many patients may have temperamental problems—anger and/or extreme abandonment issues—that persist after the remission of symptoms and that hold them back socially and vocationally. “All of our manualized treatments for BPD are aimed at acute symptoms—self-mutiliation and suicidality—and those are the symptoms that remit the most quickly,” she told Psychiatric News.

She said that a rehabilitation model of treatment incorporating training in life skills—use of public transportion, budgeting, personal care, and vocational training—is key to fully addressing the recovery needs of patients who achieve remission of BPD symptoms.

The study's other notable finding was that despite the difficulty many patients have in achieving full recovery, both remission of symptoms and full recovery, when they do occur, tend to be stable over time. Of those who achieved recovery, only 34 percent relapsed. Of those who achieved a two-year remission of symptoms, 30 percent had a symptomatic recurrence, and of those who achieved a sustained remission at four years, only 15 percent experienced a recurrence.

Zanarini and colleagues noted in their report that those rates compare favorably with remission and recurrence rates for common Axis I disorders studied longitudinally, such as major depression and dysthymic disorder. “[T]he high rate of sustained symptomatic remission and the low rate of symptomatic recurrence after sustained remission are among the most optimistic findings about borderline personality disorder reported to date,” they said.

In an interview with Psychiatric News, Zanarini said, “Depression and bipolar disorder tend to remit quickly but recur much more often. Recovery from BPD is more akin to the process of maturation. It occurs slowly, but once you achieve a certain level, you stay there, and it takes some enormous stressor to push you back.”

Joel Paris, M.D., an expert in BPD, reviewed the study for Psychiatric News. He said that it confirms and extends findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study and the McLean Study of Adult Development. This study found that while symptomatic improvement is sufficient for many patients to stop meeting criteria for the disorder—such as no longer cutting themselves or overdosing—functional improvement is much slower.

“The study suggests that while BPD is by no means incurable, many patients continue to function at a low level for years,” Paris said. “So what are the clinical implications? On the one hand, when we thought that BPD was a life sentence, we avoided treating patients who can in fact be helped. And some people do make a full recovery, going on to live normal lives. On the other hand, other cases are more chronic. If we become too optimistic, we may mislead our patients into expecting the impossible and not provide the supportive and rehabilitative services they need.”