“Children are following maladaptive adult advice about how to handle bullying, and it doesn't work,” Stan Davis, L.C.S.W., told attendees at the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) meeting in New York in October. “If we give kids advice that doesn't work, they won't come back to us.”

Davis and his colleague Charisse Nixon, Ph.D., sought to learn more about peer mistreatment among American students by conducting the Youth Voice Project, asking 13,000 students in 12 states about being called names, hit, threatened with physical violence, or socially excluded. They also asked what the children did about it and how well those responses worked.

Davis is a child and family therapist and a school guidance counselor in Wayne, Maine; Nixon is an associate professor of psychology at Penn State Erie. They are still analyzing their data but presented some preliminary results at the AACAP meeting.

About 22 percent of their sample reported some level of bullying, from mild (“bothered me a little”) to severe (“I feel unsafe or threatened . . .”).

Special-education students, sexual minorities, and racial minorities came in for disproportionately harsh treatment. About 46 percent of African-American students and 40 percent of Asian-American students said that peer mistreatment focused on race, compared with 7 percent of white students. Regardless of race or gender, looks and body shape were also prime targets of bullies.

Sexual minorities are particular targets, as the nation found out last fall when Tyler Clemente, a student at Rutgers University, committed suicide after his roommate videoed Clemente engaged in sexual activity with another man and posted the clip on the Web.

Davis and Nixon developed a list of the strategies that adults typically offer to students who are bullied. Many sound familiar: “Pretend it didn't hurt,” “Tell them to stop,” “Walk away,” “Tell an adult at school,” “Hit them back.”

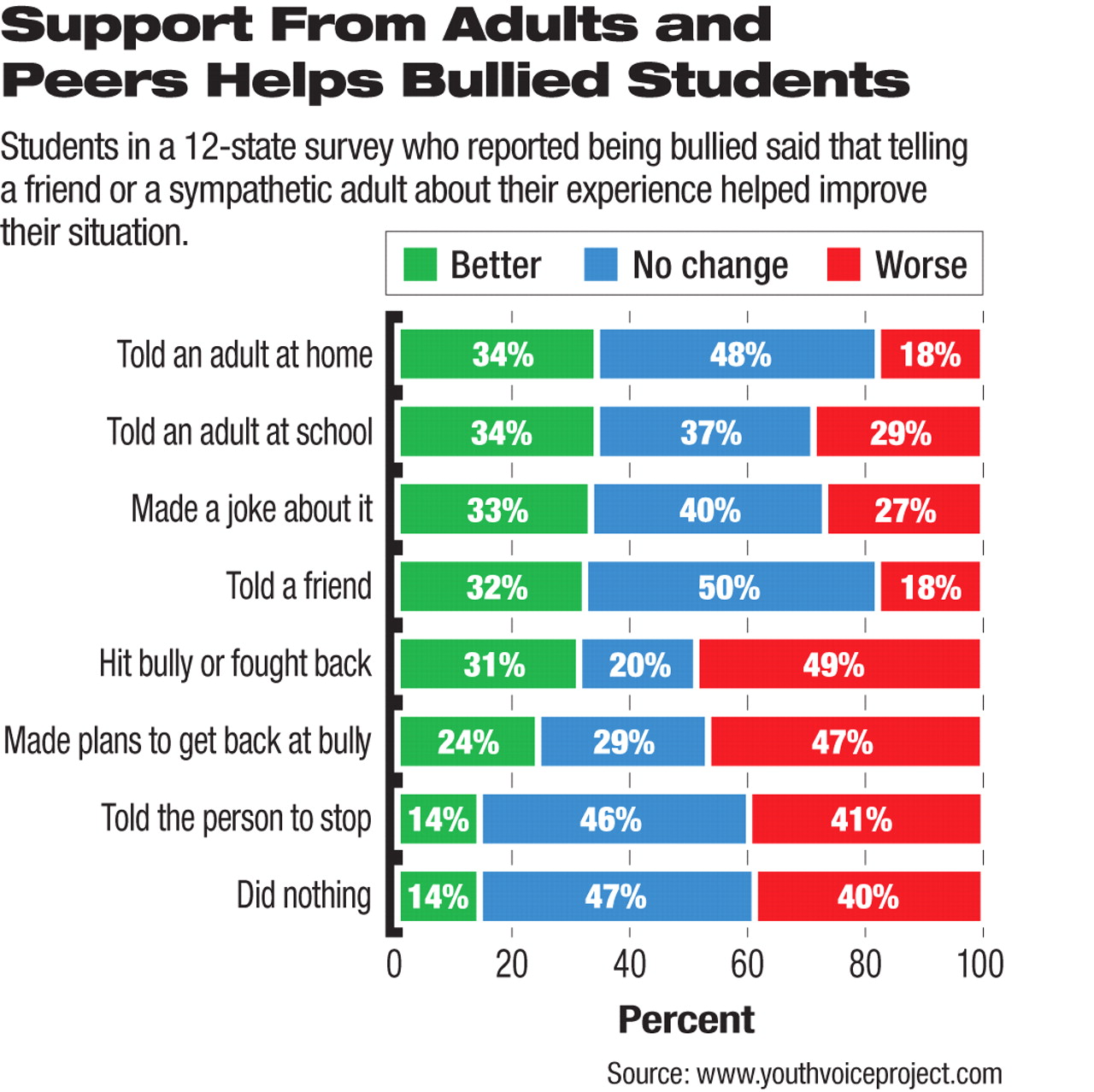

The researchers then asked which of these or other strategies worked and which made the situation worse. They found that the students' real-world experiences upset the common wisdom.

All those traditional remedies led to worse outcomes.

“Overall, situations improved in only one-third of cases after an action by the victimized student alone,” said Davis. “But when asked what made things better, 3 out of 4 kids said getting support from others was most helpful.”

Best of all was “telling an adult at home.” Other helpful strategies were telling a friend, making a joke of the situation, or telling an adult at school.

“The important thing is to CARE: connect, affirm, respond, empower,” he said.

The most negative outcomes came when adults told the children to “stop tattling.”

“Those words have got to go,” Davis emphasized. “They invalidate the child's experience and say, ‘I deny your right to tell your story.’”

Davis and Nixon found large school-to-school variations in student responses, a factor that they intend to study in the future.

Adults—whether parents, teachers, school counselors, coaches, or others—need to not only listen sympathetically after students confide in them, but to check in with them from time to time to see how they're doing, said Davis.

Parents and students should also document incidents, present their findings to school principals, and ask if such behavior is acceptable, he said. “Then ask what they will do about it.”

Programs targeting perpetrators may reduce the harm they cause, Davis said.

“Most benefit from clear rules for peer behavior based on risk of harm; small, fair, and escalating consequences for breaking those rules; helping them create and practice new behaviors; building positive peer norms; and letting them know when they are being kind,” he said in an interview. “More aggressive youths may have severe impairments or trauma or lack of social skills that require more in-depth, individualized, and longer-term interventions—and not just at school.”

Many youngsters surveyed also found support from their peers. Children who were mistreated said that the situation got better when other children talked to them, spent time with them, called them on the phone, or helped them escape from their tormentors.

“But phrases like ‘stand up for your friends’ are too confining,” said Davis. “They don't mean getting in someone's face but rather offering support to the target.”

In addition to listening sympathetically, adults and friends can direct young people to settings where they are not going to be bullied, like athletics or arts, and can experience competence and build resiliency.

“In short, young people were telling us that stopping bullying is important, but so is stopping the harm that results from it,” he said.