Army soldiers returning from Iraq were two to four times more likely to report mental health problems when completing questionnaires anonymously than in routine screening.

"This study indicates that the [Post-Deployment Health Assessment] screening process misses most soldiers with significant mental health problems and adds to the growing literature suggesting that the initial PDHA is not optimal in identifying those most in need of services," wrote Col. Christopher Warner, M.C., and eight colleagues in the October Archives of General Psychiatry.

"This is a tremendously important paper," said former Army psychiatrist Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, M.D., M.P.H., now chief clinical officer of the District of Columbia Department of Mental Health. "It reinforces scientifically what we've heard anecdotally for years."

All troops must fill out a Post-Deployment Health Assessment (PDHA) within 30 days before their return to the United States. This form and a follow-up exam by a primary care clinician are designed to detect any health problems. Soldiers undergo a second screening three to six months after they return home.

Both of these tests include questions about depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other mental health problems, along with general medical problems, and allow for referral for further evaluation and treatment. The information is entered on the soldier's electronic medical record, as well.

However, for many reasons, soldiers may not honestly report their mental health status on the PDHA. They worry about the effects of a diagnosis of mental illness or a record of treatment on their career and on their relations with superiors or fellow soldiers. Many also believed that a positive outcome on the PDHA would mean a delay in returning home, although that was never officially Army policy, said Ritchie. The six-month follow-up screening was partly intended to detect conditions not revealed on the PDHA.

Thus, Army researchers wanted to see whether completing questionnaires anonymously might provide a different pattern of responses to mental health screening questions compared with the usual health screens.

Warner and colleagues asked 2,500 members of a brigade about to leave Iraq for Fort Stewart, Ga., to fill out the anonymous form as well as the usual PDHA. Of those, 1,712 (68.5 percent) participated. Because participation was voluntary, the sample was not random.

The anonymous survey used the same questions as the PDHA about depressed mood and anhedonia (from the PHQ-2), posttraumatic stress disorder (from the four-question Primary Care PTSD Screen), and suicidal ideation (one question from the PHQ-9). In addition, the survey asked questions about interest in receiving help, stigma, and barriers to care.

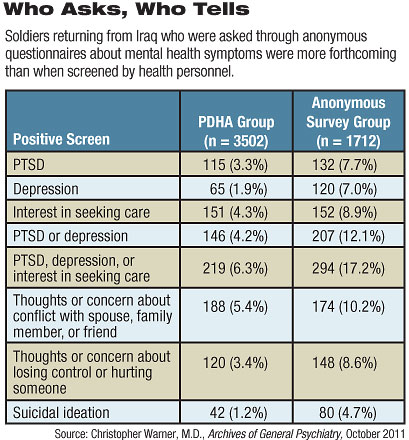

There were striking differences in the responses to the two surveys.

Only 4.2 percent of the soldiers completing the routine PDHA met criteria for depression or PTSD, but 12.1 percent on the anonymous screen did so. Only 5.4 percent on the PDHA said they were concerned about conflicts with spouses or family members, compared with 8.6 percent on the anonymous survey. And just 1.2 percent admitted to suicidal ideation on the open assessment versus 4.7 percent on the anonymous one.

Reported mental health status explicitly affected a soldier's willingness to answer honestly on the routine screenings, said the authors. Respondents who screened positive for depression or PTSD also said they were less likely to report those symptoms on the PDHA.

In addition to career issues and stigma, soldiers may not wish to report mental health problems because of "a lack of confidence in the mental health services that are available," according to the study.

An earlier study by Warner found that coupling initial screening with immediate follow-up evaluations by mental health professionals—rather than simply giving a referral to a later appointment at a different site—resulted in a higher rate of engagement in care.

"There's a fantasy that we can screen for PTSD or suicidality," agreed Ritchie in an interview. "We should be thinking of other interventions besides screening, like integrating mental health care into the same clinics as primary care. In too many places the mental health waiting room is set off by itself, so a soldier's presence there betrays his diagnosis."

"These findings reinforce the continued need for the military to develop effective strategies for encouraging personnel to seek assistance," concluded Warner and colleagues.