According to a prominent theory of alcoholism, the neurotransmitter glutamate excites neurons in the brain during alcohol withdrawal, and such excitability in turn contributes to alcohol craving and relapse.

Animal research has supported this theory. Now human research does as well.

The study, conducted by German scientists, was reported online September 12 in Biological Psychiatry.

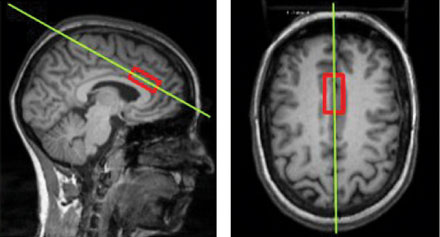

Wolfgang Sommer, M.D., Ph.D., group leader at the Institute of Psychopharmacology of the Central Institute for Mental Health in Mannheim, Germany, and his colleagues used state-of-the-art magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to measure glutamate levels in the anterior cingulate cortex of 47 alcohol-dependent subjects during detoxification and of 57 healthy control subjects.

The anterior cingulate cortex, which lies in the front part of the brain, has been heavily implicated in alcohol dependence.

Each subject underwent a 90- to 120-minute MRS session. The alcohol-dependent subjects were given their session at the beginning of signs of alcohol withdrawal and before the application of benzodiazepines became necessary.

The scientists found significantly higher levels of glutamate in the anterior cingulate cortex of the alcohol-dependent subjects during alcohol withdrawal than in the anterior cingulate cortex of the control subjects.

"Obtaining MRS data from patients in acute alcohol withdrawal is highly challenging and has, to our knowledge, so far not been achieved [by any other groups]," they noted. "[Thus] our data provide first-time direct support from humans for the glutamate hypothesis of alcoholism."

Furthermore, in a rodent model of human alcoholism, the scientists not only confirmed their human results, but also found a high glutamate to glutamine ratio in the medial prefrontal cortex during alcohol withdrawal. Glutamine is a metabolite of glutamate. Moreover, the ratio seemed unaffected by alcohol intoxication, but increased rapidly during acute withdrawal and remained high even in a short period beyond withdrawal. "It remains to be seen whether this response provides information that could be used clinically as a biomarker for severity of alcohol dependence," the scientists wrote.

"This is an excellent study demonstrating the importance of glutamate as a signal for alcohol withdrawal," Bankole Johnson, M.D., Ph.D., chair of psychiatry at the University of Virginia and an internationally recognized alcoholism expert, told Psychiatric News. "This research opens the door to the development of antiglutaminergic agents to treat alcohol withdrawal, prevent relapse, and reduce drinking."

Psychiatric News asked Sommer about this possibility. He replied that acamprosate, which is already on the market to treat alcoholism, is actually considered an antiglutaminergic compound. However, other antiglutaminergic compounds are also "a major focus in medication development for relapse prevention. . . . They may surpass acamprosate, but there will be no magic bullet. The important issue will be to identify responders for the various compounds. Here, MRS may be of help in identifying patients with high glutamate levels; they should be the ones who benefit most from an antiglutaminergic approach."

Asked whether there is any connection between the alcohol-metabolizing enzymes in the liver that tend to protect people from alcoholism and the rise of glutamate levels in the brain during alcohol withdrawal in alcohol-dependent individuals, Sommer said, "To my knowledge, this question has so far not been studied. We need much larger numbers of patients with comparable MRS assessments of glutamate levels to address the genetics of the central glutamate response during withdrawal."

The study was funded by the German Research Society.

An abstract of "Translational Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Reveals Excessive Central Glutamate Levels During Alcohol Withdrawal in Humans and Rats" is posted at < www.biologicalpsychiatryjournal.com/article/S0006-3223(11)00781-5/abstract >.