Medicaid patients receiving Medicare prescription drug benefits who were previously stable on their medications but had to switch medications because clinically indicated refills were not cov ered or approved experienced significantly higher rates of adverse events, including emergency department visits, hospitalizations, homelessness, and incarceration.

That was the finding from an analysis of the effect of the 2006 transition to the new Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Pro gram on medication access and related adverse events for “dual-eligible” patients with serious mental illness—that is, patients who are eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare. The data were presented by Joyce West, Ph.D., policy research director at the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education, at APA’s 2011 Institute on Psychiatric Services in October in San Francisco. The analysis was also published in the October Journal of Psycho-pharmacology.

The analysis confirmed earlier studies and anecdotal reports of widespread problems with accessing medica tions on which patients had previously been stable in the first year of the transition to Part D and revealed a striking correlation of these access problems with severe adverse events (see Key Points).

“These findings support caution in making medication switches for patients who are generally stable on their medication regimens,” said West, the lead author. “And they provide substantiation for policies promoting medication continuity and minimizing medication changes for clinically stable patients.”

In the study, 968 psychiatrists randomly selected from the AMA Masterfile provided data on 986 systematically selected dual-eligible patients. Data were collected on patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, including DSMIV diagnoses, general medical conditions, psychiatric symptom severity, and medications currently prescribed.

Clinicians in the sample provided information on whether the patient was stable on a clinically indicated or desired medication but switched to a different medication because clinically preferred medication refills were not covered or approved. And they reported any currently prescribed medications that were not clinically preferred, but were prescribed due to insurance limitations.

Finally, the clinicians reported all adverse events associated with medication switches, including psychiatric emergency department visits, psychiatric hospitalizations, homelessness, incarceration, and suicidal and violent ideation or behavior.

Analysis revealed that 28 percent of patients experienced some form of medication switch during the study period because a clinically indicated or preferred drug—or the refill of that drug—was not covered or approved. The medications that most commonly could not be prescribed, despite being clinically indicated or preferred, were (in rank order) SSRI antidepressants, atypical antipsychotics, nonbenzodiazepine sedative/ hypnotics, other antidepressants, benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers, and stimulants.

The specific drugs most commonly not covered or approved were Lexapro, Ambien, Cymbalta, Risperdal, Wellbutrin, and Abilify.

West explained that although 20 percent of the switched patients in the study were switched from a brand to generic medication, the majority of these switches were to nonpreferred formulations of the medication—either a medication administered by different routes (oral versus injectable) or with different rates of absorption (controlled, extended, or sustained-release formulations). For only 5.6 percent of the patients with a medication switch due to prescription drug coverage did the treating physician want to prescribe the branded version of a generic medication with the same formulation.

And most of these medication switches were clinically significant: more than half involved a switch to a different, clinically nonpreferred medication within the same class, and nearly one-third involved a switch to a nonpreferred medication in a different class.

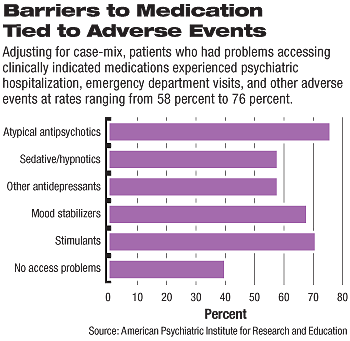

Analysis of the case-mix adjusted probability of adverse events associated with inability to prescribe a medication showed that patients who had problems accessing a clinically indicated or preferred atypical antipsychotic had the highest likelihood of an adverse event (76 percent predicted probability, followed by stimulants (71 percent), mood stabilizers (68 percent), and other antidepressants (58 percent).

By comparison, there was a 40 percent predicted probability of an adverse event for those who did not experience a medication switch or access problems (see chart).

“Prescription drug coverage and management policies that restrict access to medications considered clinically indicated and preferred by physicians should be more carefully scrutinized and monitored to ensure the policies promote clinically appropriate treatment and minimize risks to patients,” West said.

Key Points

Forty-two percent of Medicare-Medicaid eligible patients experienced a medication switch due to inability to access a clinically indicated or preferred medication during the period of transition to the Medicare Part D program in 2006.

Most of these medication switches were clinically significant: More than half involved a switch to a different, clinically nonpreferred medication within the same class, and nearly one-third involved a switch to a nonpreferred medication in a different class.

Adverse events were significantly associated with medication switches resulting from inability to access clinically indicated or preferred medications.

Patients who had problems accessing a clinically indicated or preferred atypical antipsychotic had the highest likelihood of an adverse event.