Bipolar disorder is highly heritable. Research has shown that adolescents who have a first-degree relative with bipolar disorder are at an eightfold or more increased lifetime risk of developing bipolar disorder themselves. Having a second-degree relative with the illness also increases risk, as does having more than one family member with it.

But what can individuals who have one or more family members with bipolar disorder expect to experience while they are still children? Perhaps nothing, because most offspring in families with bipolar disorder will not develop the illness. Others, however, may experience an anxiety disorder or an externalizing disorder, then a major depression or bipolar disorder, a new study suggests.

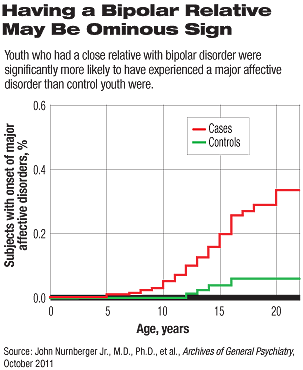

The study was headed by John Nurnberger Jr., M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at Indiana University and director of its Institute of Psychiatric Research. Results appeared in the October Archives of General Psychiatry.

The study included 141 youth, with an average age of 17, who had at least one relative with bipolar disorder. A total of 114 had a parent with bipolar, 13 had an older sibling with bipolar, 13 had an aunt or uncle with bipolar, and one had a grandparent with bipolar. Eighty-five of the youth also came from families that had more than one relative with the illness. The study also included 91 youth of a similar age whose parents did not have bipolar disorder and whose parents had no first-degree relatives with a psychiatric hospitalization. These youth served as controls.

The researchers obtained the subjects’ psychiatric histories by interviewing them and their parents and also by consulting their medical records. The researchers found that certain childhood psychiatric diagnoses were significantly more prevalent among the cases than among the controls, after taking age, gender, and ethnicity into consideration.

Twenty-three percent of the cases, but only 4 percent of the controls, had experienced a major affective disorder—that is, major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. And whereas 9 percent of the cases had experienced bipolar disorder, none of the control group had.

Moreover, among subjects manifesting major affective disorders, there was a four times greater risk of an anxiety disorder or of an externalizing disorder compared with subjects without major affective disorders. Also, in subjects, but not controls, a childhood diagnosis of an anxiety disorder or externaliz ing disorder predicted the later onset of major affective disorders. (The relative risk was 3 for an anxiety disorder and 4 for an externalizing disorder.)

“I think it surprised us initially that we didn’t find many substance use disorders or anxiety disorders in high-risk offspring,” Nurnberger told Psychiatric News. “But then we realized that those disorders were increased in the kids who went on to develop depression or mania/ hypomania.”

“The clinical implications of these findings are that family history of bipolar disorder matters a lot in that childhood disorders such as anxiety disorder or con duct disorder may predict a mood disorder during adolescence in youngsters with a positive family history, but not in youngsters without the family history,” Nurnberger said.

These are only the initial results from a longitudinal study of subjects at risk for bipolar disorder, Nurnberger pointed out. “We are continuing to follow the subjects in this sample and are adding new subjects as well. We are also adding in genetic marker and biological marker studies.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.