Telomeres are DNA-protein complexes that cap the ends of chromosomes. Each time a cell divides, the telomeres shorten a bit. If the telomeres become too short, a cell is unable to divide further and dies.

Not just chronological aging, but various life adversities can shorten telomeres, scientists are finding (Psychiatric News, June 2, 2006; July 1).

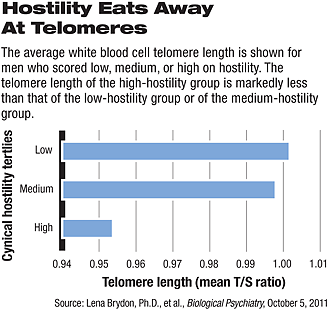

And now it looks as if a negative personality trait—hostility—can chip away at telomere length as well, at least in men. That is a key finding of a study led by Lena Brydon, Ph.D., a senior research fellow at University College London in England and published online October 5 in Biological Psychiatry.

Hostility has long been associated with an increased risk of age-related disease and all-cause mortality. But the biological mechanisms mediating the link between hostility and disease and death have been unclear. Thus Brydon and her colleagues decided to see whether hostility adversely affects health by curtailing telomeres and hastening cell death.

Their cohort included 434 men and women who were part of the Whitehall II cohort, that is, a cohort from a larger study investigating psychosocial, demographic, and biological risk factors for coronary heart disease. The subjects were evaluated with an instrument called the Cook Medley Hostility Scale, a widely used self-report measure of hostility, assessing cynical, mistrustful attitudes toward others and also, to some extent, aggressive reactions to people. The subjects were asked to score themselves from 0 to 10 on questions such as “It is safer to trust nobody,” “Most people make friends because friends are likely to be useful to them,” “I think most people would lie to get ahead,” “No one cares much what happens to you,” and “Most people are honest chiefly through fear of being caught.” The subjects’ scores on this instrument were found to range anywhere from 0 to 10, with an average response of 3.

The subjects also provided blood samples so their white cells could be measured for telomere length. Finally the researchers looked to see whether they could find a significant link between high hostility scores and shorter telomere length, taking possibly confounding variables, such as age, body mass index, cardiovascular measures, and health behaviors, into consideration.

Indeed, they did find a significant association between high hostility scores and shorter telomere length—but only for men.

Thus “our findings suggest that telomere attrition might represent a novel mechanism mediating the detrimental effects of hostility on men’s health,” Brydon and her group concluded. In other words, hostility might be able to speed up the telomere shortening that normally occurs with men’s chronological aging, and such fast-tracked telomere shortening might then make the men prematurely susceptible to diseases for which they are at higher risk as they grow older.

The good news, however, as Brydon told Psychiatric News, “is that telomere length is more dynamic than previously thought and can in fact decrease, remain stable, or increase with age, depending on the individual and the environment.”

A five-year prospective analysis of 608 patients with stable coronary artery disease, she explained, found three distinct leukocyte telomere trajectories: telomere shortening in 45 percent, telomere maintenance in 32 percent, and telomere lengthening in 23 percent. In that study, the rate of telomere shortening over five years was inversely related to baseline blood levels of omega-3 fatty acids, a dietary factor associated with prolonged survival in cardiac patients. Then a separate analysis of 236 healthy elderly men and women observed a similar pattern of leukocyte telomere changes over time, with 30 percent of the sample showing telomere shortening, 46 percent showing telomere maintenance, and 24 percent showing telomere lengthening.

Corresponding findings have also been reported in healthy young adults and in a large multigenerational cohort followed over 10 years, she said.

The study was funded by the British Heart Foundation, United Kingdom Medical Research Council, and Bernard and Barbro Fund.

An abstract of “Hostility and Cellular Aging in Men From the Whitehall II Cohort” is posted at <www.biologicalpsychiatryjournal.com/article/S0006-3223(11)00855-9/abstract=.