A few years ago, Zindel Segal, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, and colleagues developed an intervention called mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). It was designed to help people who have experienced repeated bouts of depression avoid another one.

“The emphasis in early sessions of MBCT,” Segal explained to Psychiatric News, “is on developing skills in affect regulation via intensive training in mindfulness meditation. Elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are incorporated into later sessions to help patients [deal] with relapse triggers and to schedule mastery and pleasurable events in the face of low mood. One feature that both mindfulness training and CBT share is helping patients stand back and observe their thoughts as ideas or mental events rather than as true reflections of reality.”

Research evidence suggesting that the intervention is effective is growing. For example, Swiss researchers and Segal reported in the May 2010 Journal of Affective Disorders that time to relapse was significantly longer in subjects getting MBCT and treatment as usual than in subjects simply getting treatment as usual.

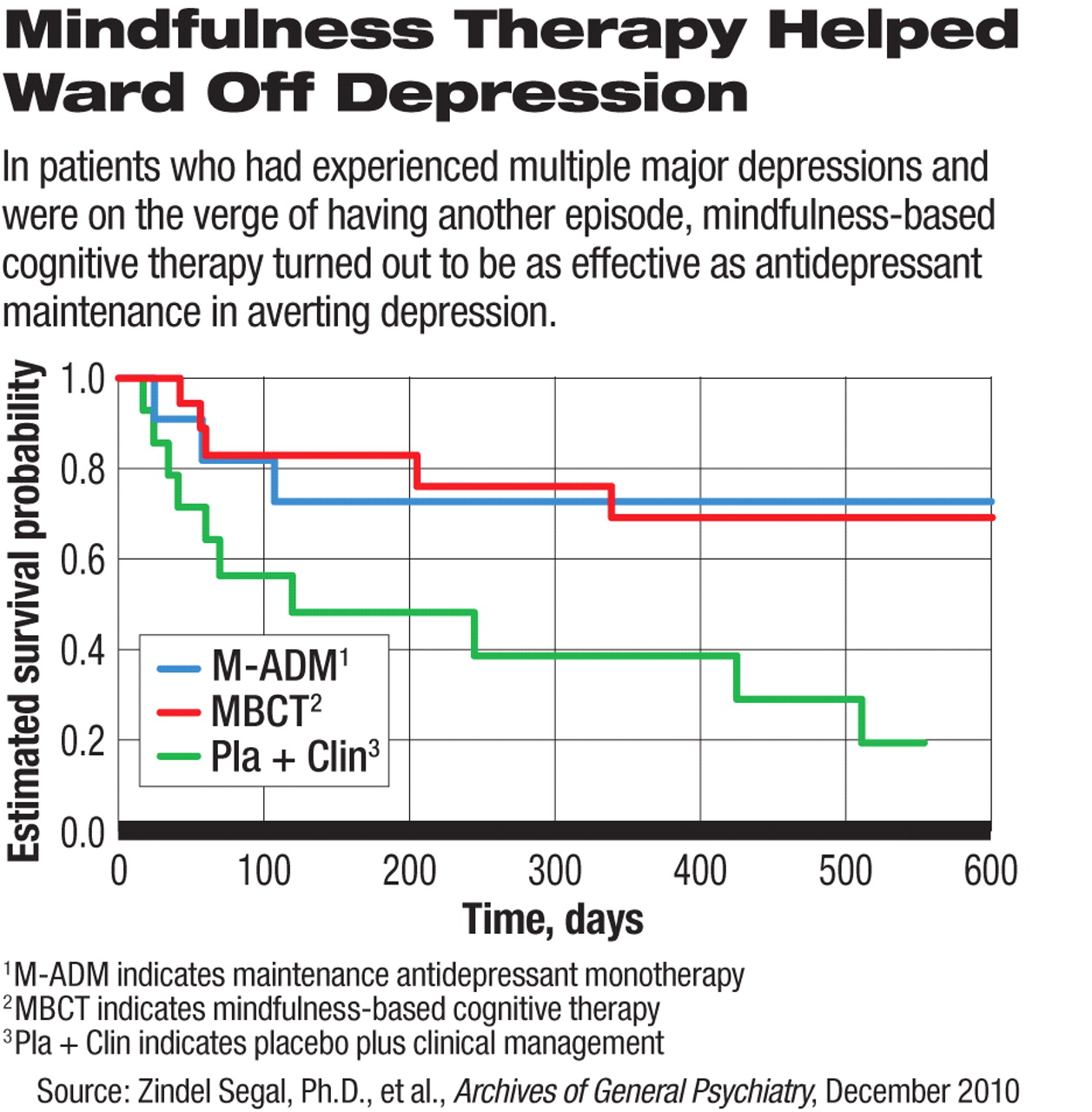

And now a new study reported by Segal and other Canadian researchers in the December 2010 Archives of General Psychiatry suggests that MBCT is significantly better than a placebo, and as good as antidepressant maintenance therapy, in preventing relapse in depression-prone individuals who are at risk of having another depressive episode.

The study included 84 subjects who were aged 18 to 65 and had had at least two bouts of major depression and who had been in remission for at least seven months. They were assigned to one of three treatment arms—MBCT, antidepressant maintenance, or a placebo. MBCT was administered in eight weekly two-hour group sessions. It also included daily homework exercises and optional participation in mindfulness meditation classes. All subjects were followed up for 18 months to see whether they relapsed. Relapse was defined as a return, for at least two weeks, of symptoms sufficient to meet criteria for a major depression according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.

After evaluating outcomes for the three groups, the researchers found no significant differences when considering only those who had not been especially vulnerable during remission (that is, those who had scored 7 or less on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression). Relapse rates were 62 percent for the MBCT group, 59 percent for the antidepressant maintenance group, and 50 percent for the placebo group.

(The researchers measured the time to the first relapse following randomization. They also measured time to relapse, and, as was the case with the comparison of relapse rates, the three groups of patients did not differ on this variable.)

The researchers were surprised by these findings and had no ready explanation for them, they admitted in their paper.

However, a significant difference in outcome was found when researchers considered only subjects who had been especially vulnerable during remission (that is, those who had scored higher than 7 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression). MBCT and antidepressant maintenance therapy were significantly and comparably better than a placebo in warding off another depressive episode.

Specifically, relapse rates were 28 percent for the MBCT group, 27 percent for the antidepressant maintenance therapy group, and 71 percent for the placebo group.

These findings “highlight the importance of maintaining at least one active long-term treatment in recurrently depressed patients whose remission is unstable,” the researchers asserted. “For those unwilling or unable to tolerate maintenance antidepressant treatment, MBCT offers equal protection from relapse during an 18-month period.”

How MBCT prevents depression relapse in those at high risk for it is not known. But it may involve the insula and right lateral prefrontal cortex regions of the brain, the researchers speculated, based on findings of another study they conducted. In this study, MBCT recipients and control subjects were exposed to sadness-provoking material. The former demonstrated less suppression of the insula and right lateral prefrontal cortex than the latter did.

When Psychiatric News asked Segal whether there is any particular aspect of the MBCT intervention that is critical in preventing depression in at-risk patients, he replied, “Analyses of data from multiple trials of MBCT indicate that the continued practice of mindfulness, once treatment has ended, is strongly predictive of staying relapse free. This does not mean that patients have to continue practicing for 40 minutes per day, but some type of daily experience of mindfulness, whether briefly checking in with the breath, taking a three-minute breathing space, or paying attention to how your body feels if you are waiting to check out at the supermarket, can help patients regulate low moods and prevent them from spiraling into a clinical relapse.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.