It is the latest turn in a now 30-plus year evolution in psychiatry’s understanding of homosexuality and involves a figure who has been prominent in that story throughout.

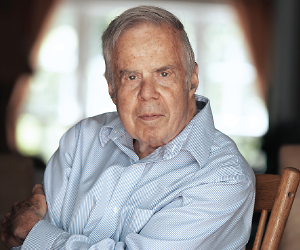

Robert Spitzer, M.D., well known to APA members as a leader in the development of DSM, renowned as instrumental in removing homosexuality from the diagnostic manual as a disorder in 1973 and—paradoxically—the author of a deeply controversial study in the early part of the last decade suggesting that “reparative therapy” could help gay people change their sexual orientation—has now renounced the findings of that controversial study.

In a letter to the editor of the Archives of Sexual Behavior, where the study appeared in 2003, Spitzer issued a mea culpa. “I believe I owe the gay community an apology for my study making unproven claims of the efficacy of reparative therapy,” he wrote. “I also apologize to any gay person who wasted time and energy undergoing some form of reparative therapy because they believed that I had proven that reparative therapy works with some ‘highly motivated’ individuals.”

Spitzer’s study, first presented at APA’s 2001 annual meeting, generated enormous public attention and controversy, and his turnabout last month has been equally spectacular, resulting in an article in the New York Times with the headline, “Psychiatry Giant Sorry for Backing Gay ‘Cure.’ ”

In an interview with Psychiatric News, Spitzer said it was an apology long in the making. He said he had his doubts about the study from the beginning, particularly when he read the almost uniformly negative commentaries that accompanied the study’s publication. Then, last month a reporter from The American Prospect, Gabriel Arana, who had undergone reparative therapy as a teenager, interviewed Spitzer.

“Gabriel said he was going to write his story and mention that I had my reservations about it,” Spitzer told Psychiatric News. “So I decided it was up to me to explain what my reservations were rather than rely on him to tell it.”

Was it hard to do? “Yes, it was,” Spitzer said. “But I can tell you I felt better as soon as I had done it.”

Leaders in the gay community hailed Spitzer’s action, saying it puts to rest what they believe are false claims about the efficacy of so-called reparative therapy.

Ex-Gay Movement Touted Study

Psychiatrist Jack Drescher, M.D, told Psychiatric News that the so-called ex-gay movement had clung to Spitzer’s study as evidence for the efficacy of reparative therapy. “There’s very little scientific evidence that people can change their sexual orientation, but individuals in the ex-gay movement try to lend their beliefs a patina of scientific credibility,” he said. “Spitzer’s study seemed to give them that patina, which he himself has just taken away.”

Drescher has served since 2007 as a member of APA’s DSM-5 Work Group on Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders. He is author of Psychoanalytic Therapy and the Gay Man and emeritus editor of the Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health.

Drescher, who describes himself as a friend and colleague of Spitzer, called him a pivotal figure in the evolution of gay rights. “He was instrumental in removing homosexuality from DSM in 1973,” he said. “That would never have been accomplished without the critical thinking he brought to the subject. It was a watershed in American psychiatry, and Spitzer was a major actor in changing social views about homosexuality. I don’t think we would be talking about gay marriage today if APA hadn’t gotten out of medicalizing homosexuality.”

Commentaries Cite Study Flaws

The research question that Spitzer posed more than a decade ago—is reparative therapy for people who wish to change their sexual orientation effective?—was a reasonable one. But the design for testing the question and the interpretation of results were highly problematic, as many people pointed out when the survey was first presented at APA’s annual meeting.

Survey participants were 200 self-selected individuals (143 males, 57 females) who reported at least some minimal change from homosexual to heterosexual orientation that lasted at least five years. They were interviewed by telephone, using a structured interview that assessed same-sex attraction, fantasies, yearning, and overt homosexual behavior (Psychiatric News, July 6, 2001).

The majority of participants gave reports of change from a predominantly or exclusively homosexual orientation before therapy to a predominantly or exclusively heterosexual orientation in the year after the therapy, but reports of complete change were uncommon. Spitzer concluded at the time, “There is evidence that change in sexual orientation following some form of reparative therapy does occur in some gay men and lesbians.”

A total of 26 commentaries were published along with the study, many of them extremely negative and focusing on two main flaws: the difficulty of determining credibility of accounts of change and the failure to specify any particular type of therapy. Moreover, critics noted, all of the reports of change came from a self-selected group of people highly disposed, typically for religious reasons, to view their homosexuality as aberrant and unnatural.

So, for most commentators the question of whether reparative therapy was generally effective was, on the basis of the survey design, unanswerable; far less so was the more important question of whether reparative therapy was generally advisable.

In 1998 APA Trustees had approved the “Position Statement on Psychiatric Treatment and Sexual Orientation,” which stated that APA “opposes any psychiatric treatment, such as reparative or conversion therapy, which is based upon the assumption that homosexuality per se is a mental disorder or based upon the a priori assumption that the patient should change his/her sexual homosexual orientation.”

The statement also noted that “[t]he potential risks of reparative therapy are great, including depression, anxiety, and self-destructive behavior, since therapist alignment with societal prejudices against homosexuality may reinforce self-hatred already experienced by the patient.”

That statement was followed by another position statement in 2000 that elaborated on the inconclusive evidence about reparative therapies.

Zucker told Psychiatric News in an interview that while the methodological shortcomings in Spitzer’s study were apparent, it was “the first systematic collection of data about a very interesting population of people.” In an editorial that accompanied the Spitzer study when it was published in 2003, he wrote, “It is the Editor’s view that a scholarly journal is a legitimate forum to address controversial scientific and ethical issues rather than leaving the complexity of the attendant discourse to ‘the street.’”

During his presentation at the 2001 annual meeting, Spitzer was explicit in his opposition to the use of coercive treatment of young people. But the study was seized upon by ex-gay groups as evidence of the efficacy of reparative therapy, and as the decade wore on, the controversy threatened to overwhelm Spitzer’s many other accomplishments as a clinician and a researcher.

Drescher told

Psychiatric News, “I don’t think Bob realized at the time how his name, which is well known, would be used by people for purposes with which he didn’t agree.”