At least 48 states have implemented monitoring programs that track the prescription and sale of opioids as a way to reduce their widespread abuse. The databases identify people whose prescription drug-use patterns indicate abuse or physicians whose drug-prescribing habits appear to contribute to opioid-prescription abuse. A study published in the March Pain Medicine suggested that these programs do help reduce such abuse. Now there is evidence suggesting that they could be even more effective if they offered real-time information to pharmacies at the time that people try to fill opioid prescriptions.

This is the conclusion of a Canadian study published online September 4 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal and led by Colin Dormuth, Sc.D., an assistant professor of anesthesiology, pharmacology, and therapeutics at the University of British Columbia.

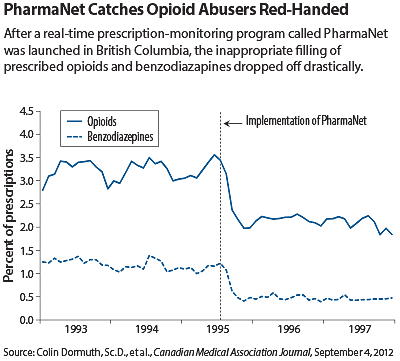

In 1995, British Columbia implemented a centralized prescription network called PharmaNet. It offered pharmacists throughout the province information about the filling of prescriptions for not just opioids, but also for benzodiazepines at the actual time that the prescriptions were being filled at a pharmacy. Before that, pharmacists didn’t know what prescriptions were being filled at pharmacies other than their own. Dormuth and his colleagues thus decided to conduct a study to compare the filling of opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions in British Columbia during the 30 months preceding the introduction of PharmaNet and during the 30 months following its implementation.

They concentrated on the inappropriate filling of opioid or benzodiazepine prescriptions for individuals on social assistance and those over age 65, since the database they used prior to the launching of PharmaNet lacked information about prescriptions for people in other groups.

They defined an inappropriately filled opioid or benzodiazepine prescription as one issued by a different physician and dispensed at a different pharmacy within seven days after a filled prescription for 30 or more tablets of the same drug. They then calculated monthly percentages of filled prescriptions for an opioid or benzodiazepine that were deemed inappropriate in their subjects during the 30 months before and after implementation of PharmaNet.

Reduction Seen in Inappropriately Filled Prescriptions

Within six months of implementation of PharmaNet, there was a drastic reduction—33 percent—in inappropriately filled prescriptions for opioids and an even greater reduction—49 percent—in inappropriately filled prescriptions for benzodiazepines.

Thus PharmaNet “was associated with large, immediate, and sustained reductions in filled prescriptions for opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines deemed inappropriate by our definition,” the researchers said. “[And] if our findings can be generalized to other jurisdictions, we estimate that such networks could eliminate millions of inappropriately filled prescriptions in the United States and Canada annually.”

“This study shows that real-time entry of prescriptions for controlled substances into a system that can be assessed by prescribers and pharmacists filling prescriptions has the potential to substantially increase safety for patients and the public,” Elinore McCance-Katz, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, and an addiction psychiatrist, told Psychiatric News.

National Network Needed

But for a system to really increase safety, it should be not only in real time, but also national, she emphasized. “The feds have spoken about a national network that would allow the ability to look at prescription data from any state the patient has been in,” she said, “[especially since] the crossing of state lines for drugs is a huge issue. I have urged them to fully fund such a program.”

Regarding the Canadian opioid-prescription monitoring study, John Renner, M.D., chair of the APA Council on Addiction Psychiatry, told Psychiatric News, “I thought it was well done, and the findings are consistent with other views and with the general opinions of the addiction psychiatry community. The evidence shows a reduction in prescription drug abuse and an improvement in the treatment management of opioid-dependent individuals.”

Renner is also associate chief of psychiatry for the VA Boston Healthcare System.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the British Columbia Ministry of Health.