Biology is not destiny, concludes a study of suicide-attempt hospitalizations among adoptees in Sweden.

The study compared adopted children whose biological parents were suicidal with those whose parents were hospitalized for other psychiatric disorders.

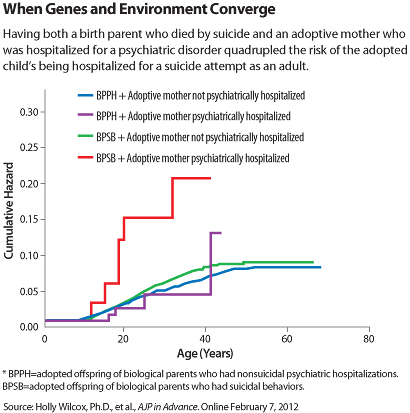

Adoptees with a biological parent who died by suicide or was hospitalized for suicidal behavior had a fourfold greater risk of a suicide attempt only if the adoptive mother was hospitalized for a psychiatric illness during the child’s childhood or adolescence, wrote Holly Wilcox, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and colleagues in AJP in Advance on February 7.

“It’s the interaction during development between the adoptee’s genetic ancestry and living with the adoptive mother that increases risk, but not either one alone,” explained child psychiatrist William Beardslee, M.D., the Gardner Monks Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, in an interview. Beardslee was not involved in Wilcox’s research.

Separating the effects of growing up with suicidal parental behavior from a childhood shadowed by some other parental psychiatric illness is a challenge, said the authors.

However, once again, Scandinavian record keeping provided valuable insights.

The researchers used several Swedish population and health registries to study 25,688 adoptees in Sweden between 1973 and 2003. Of those, 2,516 had a biological parent who had a confirmed suicide (531), uncertain suicide (116), certain suicide-attempt hospitalization (1,361), or uncertain suicide-attempt hospitalization (508). They were compared with another 5,875 adoptees with biological parents hospitalized with an International Classification of Diseases (ICD) psychiatric code. All adoptions were domestic and the registry is very complete, since private adoptions are illegal in Sweden.

Even with the large numbers in the general cohort, only 38 adoptees had the overlapping risks from both biological and adoptive parents, resulting in wide confidence intervals and limiting generalizability.

Background data on suicidality in Sweden’s general population or on biological parents without psychiatric hospitalization or death by suicide might have added context to the study, said Beardslee. It also would be valuable to know about biological parents who attempted suicide but did not need hospitalization, he said.

Unsurprisingly, adoptive parents in general were older than biological parents and had fewer lifetime psychiatric hospitalizations.

Ultimately, biology alone did not predict risk, concluded Wilcox and colleagues.

Adoptees who had a biological parent with suicidal behavior were at four times greater risk for suicide-attempt hospitalizations compared with adoptees with a psychiatrically hospitalized (but not suicidal) biological parent—but only when the adoptive mother had been hospitalized for psychiatric reasons when the child was under age 18.

“In contrast, no difference was observed between offspring of [biological parents with suicidal behavior] and offspring of [biological parents with psychiatric hospitalization] when the adoptive mother was not psychiatrically hospitalized,” wrote the researchers.

The researchers noted that the study may underestimate risk for adoptees, given that adoptive parents have been well screened for mental health and socioeconomic factors.

The effects of childhood adversity on later mental health are well known, and studies have shown the importance of treating mothers to remission, said Beardslee. “When you compare the two, the children of mothers who remit do better psychiatrically than those who do not remit.”

Maternal psychiatric illness is a modifiable factor, agreed Wilcox. Thus, identifying and treating psychiatric disorders among both biological and adoptive mothers “could be a critical step in the prevention of the generational transmission of suicidal behaviors.”