Psychiatric illness presents considerable challenges to clinicians who treat the four million Americans affected by chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (

1,

2,

3 ). Patients with HCV infection have a higher prevalence of psychiatric illness than the general U.S. population (

1,

2,

3 ), and individuals with psychiatric illness have significantly higher rates of HCV infection than the U.S. population (15 to 20 percent compared with 1 to 2 percent) (

3,

4 ). The use of therapies based on interferon-α in combination with ribavirin results in the eradication of HCV infection and viral clearance in 54 to 56 percent of patients (

5,

6 ).

Interferon-α and ribavirin treatment has been problematic among patients with HCV and psychiatric illness, because neuropsychiatric complications occur among at least half of patients undergoing treatment (

5,

6 ). Consequently, clinicians have been reluctant to offer interferon-α treatment to patients with HCV and preexisting psychiatric illness because of the risk of precipitating or exacerbating psychiatric illness. These patients could be left with no treatment and at risk of progressing to end-stage liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

The HCV clearance rates reported in the literature may not be applicable to the entire HCV-infected population because they were derived from clinical trials that excluded patients with preexisting psychiatric and substance use disorders (

7,

8 ). Other reports detailing the clinical experience with interferon-α treatment describe little success in engaging patients with HCV in treatment (

7,

8 ). These reports also cite psychiatric illness and substance use as reasons for HCV treatment ineligibility among at least half of the HCV patients evaluated. Additionally, only 10 to 15 percent of patients who were treated achieved viral clearance.

This study examined HCV treatment eligibility, utilization, and outcomes (that is, viral clearance) among patients with psychiatric illness. The objective of this brief report was to facilitate the development of better management and therapeutic approaches to engage patients with HCV and psychiatric illness in treatment and to successfully administer HCV treatments, while minimizing complications. We hypothesized that patients with HCV and psychiatric illness are frequently found ineligible for interferon-α treatment.

Methods

All patients admitted to the inpatient psychiatric and substance abuse treatment services at a Department of Veterans Affairs medical center in Virginia from 1998 to 2002 were screened for HCV infection. Patients with HCV received education and counseling about their infection during their inpatient stay. After discharge, gastroenterologists ordered confirmatory testing (HCV RNA and genotype) and arranged for liver biopsy. After approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the Salem Veterans Affairs Medical Center, we retrospectively tracked a cross-sectional representative sample of patients for HCV disease parameters, treatments offered, treatment response, and psychiatric care.

Results

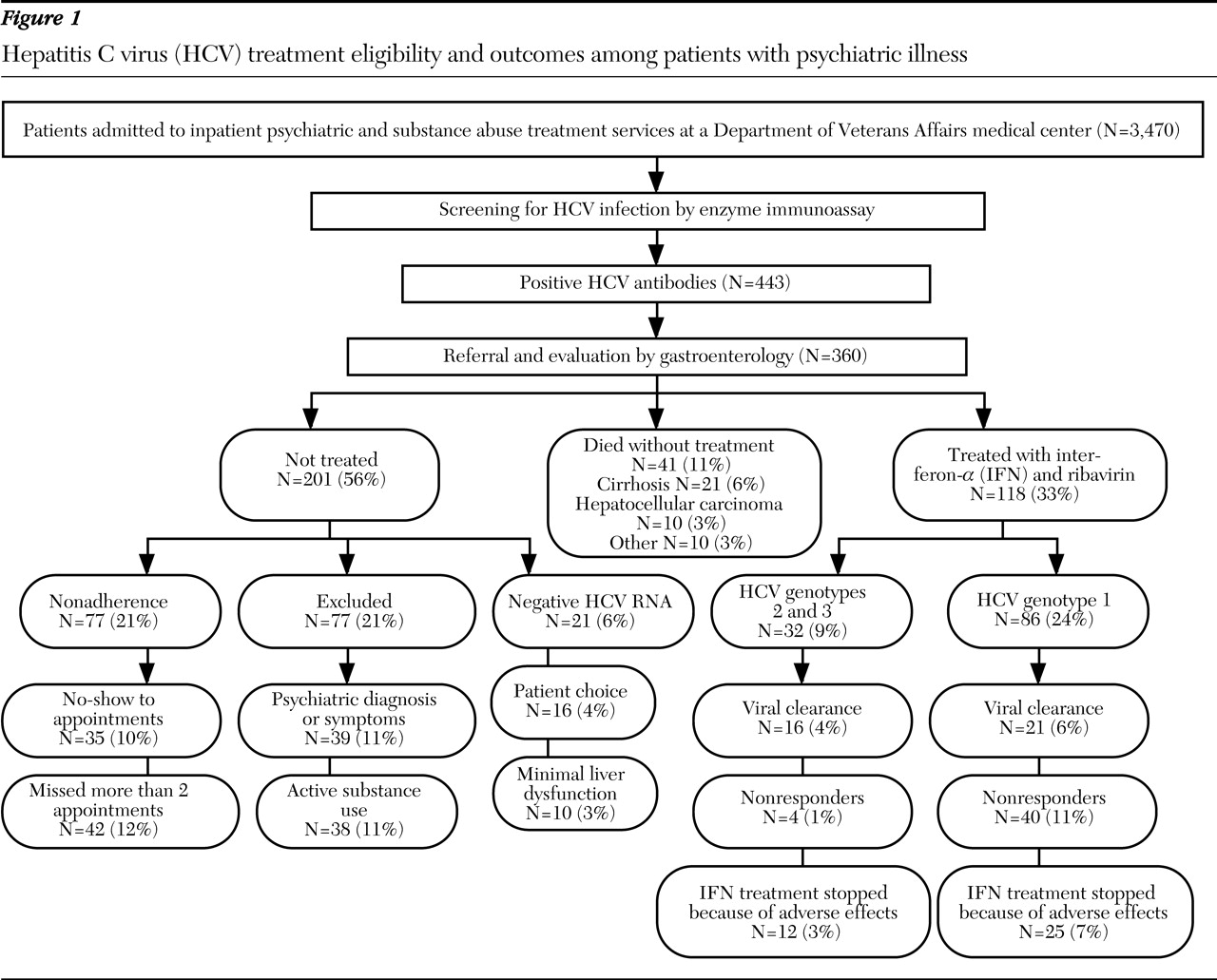

As illustrated in

Figure 1, a total of 3,470 patients were admitted to our psychiatric inpatient service during the study period, and 443 (12.7 percent) screened positive for HCV antibodies. Medical record documentation about HCV treatment was available for 360 patients (10.3 percent). No differences were found in demographic characteristics or psychiatric diagnoses between our sample and those excluded because medical record documentation of HCV treatment was absent. Our sample (N=360) was an all-male sample with a mean±SD age of 48±6 years. A total of 223 (62 percent) were white, and 137 (38 percent) were African American. Forty-one (11 percent) died during the study period without receiving HCV treatment. The causes of death included complications from cirrhosis (21 patients, or 6 percent), hepatocellular carcinoma (ten patients, or 3 percent) and other medical illnesses (ten patients, or 3 percent), and all those who died had comorbid alcohol use disorder.

Among the 319 patients who received a referral for HCV evaluation and treatment, 77 (21 percent) were nonadherent with the evaluation process—that is, they failed to keep the initial appointment or missed more than two appointments. A total of 124 of those referred (39 percent) were not treated for the following reasons: presence of psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses, that is, posttraumatic stress disorder, major depressive episode, psychotic disorder, or suicidal ideation (39 patients, or 11 percent); presence of active alcohol or drug use, that is, alcohol, cocaine, or opioid use, excluding cannabis (38 patients, or 10 percent); presence of minimal liver dysfunction (normal alanine aminotransferase) (ten patients, or 3 percent); refusal to participate in treatment (16 patients, or 4 percent); and absent HCV viremia (21 patients, or 6 percent).

A total of 118 patients (33 percent) who received a referral for HCV evaluation were treated with regular interferon-α and ribavirin, and viral clearance was successful for 37 of these patients (31 percent). Fifty percent of patients with HCV genotype 2 or 3 (16 of 32 patients) had HCV clearance, and 24 percent of those with HCV genotype 1 (21 of 86 patients) had viral clearance. Viral clearance was not achieved among 44 patients (37 percent), which includes 17 patients (14 percent) who were nonresponders (did not show reduction in HCV viral load after 12 weeks of treatment) and 27 (23 percent) who relapsed after treatment cessation. Patients who received treatment with interferon-α and ribavirin required one or more of the following strategies to manage their psychiatric illness: intensive psychiatric follow-up in the form of more frequent appointments (72 patients, or 61 percent), preemptive increases of psychotropic medications and prophylactic psychotropic medications (46 patients, or 39 percent), and enrollment in substance abuse treatment programs with aftercare treatment and counseling to maintain abstinence during HCV treatment (62 patients, or 53 percent). HCV treatment was stopped because of neuropsychiatric adverse effects—depression unresponsive to treatment, worsening bipolar illness, or suicidality—among 16 patients (14 percent) or because of medical adverse effects—anemia, thrombocytopenia, or neutropenia—among 21 patients (18 percent).

Discussion

Our results reveal several important findings about the course and management of HCV infection among patients with psychiatric illness. First, HCV infection was associated with significant mortality. Second, interferon-α combined with ribavirin can be safely administered to patients with HCV and psychiatric illness. Third, many patients with HCV and psychiatric illness were frequently found ineligible for HCV treatment because of their psychiatric illness. Fourth, nonadherence to the evaluation process leading to HCV treatment was substantial.

The mortality of HCV infection among patients with psychiatric illness was almost 11 percent, and three-fourths of these patients died from sequelae of HCV infection. These rates are several times higher than mortality rates in the general U.S. population infected with HCV (

9 ) and are particularly concerning in light of the fact that 21 percent of our patients were not offered HCV treatment because of psychiatric illness or alcohol and drug use. The exclusion of patients with psychiatric illness from interferon-α treatment is stigmatizing and may be associated with measurable mortality for a particularly vulnerable population no less deserving of treatment than HCV patients without psychiatric illness (

7,

8,

10 ).

Our results illustrate that many patients with HCV and psychiatric illness can safely undergo therapies based on interferon-α and ribavirin provided there is close psychiatric follow-up and attention to substance abuse treatment before and during interferon-α treatment. Thirty-three percent of our patients underwent interferon-α and ribavirin treatment, and successful completion and viral clearance was achieved in 25 percent of those treated. The low rate of psychiatric complication highlights the importance of an individualized and balanced risk-benefit analysis incorporating factors specific to HCV as well as prophylaxis and preemptive treatment of potential psychiatric adverse effects before offering interferon-α treatment.

At least one-fifth of our patient group was not offered treatment because of noncompliance with the evaluation process. Others reported the same difficulties in engaging 40 percent of patients in HCV treatment, mostly because of the lack of patient education about HCV and the asymptomatic nature of HCV liver disease (

5,

6 ). The inpatient psychiatric setting may have provided an ideal environment to offer HCV screening and education and served to streamline and standardize the referral process for patients with HCV to see gastroenterologists and receive HCV treatment.

We urge caution when applying our results to the treatment of HCV patients with psychiatric illness—a comprehensive risk-benefit assessment, close psychiatric follow-up, and an integrated medical-psychiatric system need to be in place before endeavoring to offer HCV treatment to patients with psychiatric illness. This retrospective review of HCV treatment outcomes in an all-male veteran population admitted to a psychiatric inpatient service may not be applicable to the entire HCV-infected population.

Future analysis of results on the use of pegylated interferons and ribavirin among patients with HCV and psychiatric illness and the introduction of HCV-specific protease inhibitors (VX-950) may show improved viral clearance rates, which would strengthen the case for HCV treatment among these patients (

5 ). Nonetheless, even patients who do not have HCV clearance in response to interferon-α treatment may achieve some benefit, because treatment may reduce both the rate of progression to cirrhosis and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marc Ghany, M.D., Donald Rosenstein, M.D., and Douha Sabouni, M.D., for helpful advice and review of initial drafts.