Egon Bittner conducted field work in the 1960s in a large West Coast city where he observed regular interaction between the police and people with mental illness over a ten-month period. On the basis of this work, Bittner described three horizons of context that explain the police decision-making process for emergency apprehensions and the provision of "psychiatric first aid": the scenic, temporal, and manipulative horizons (

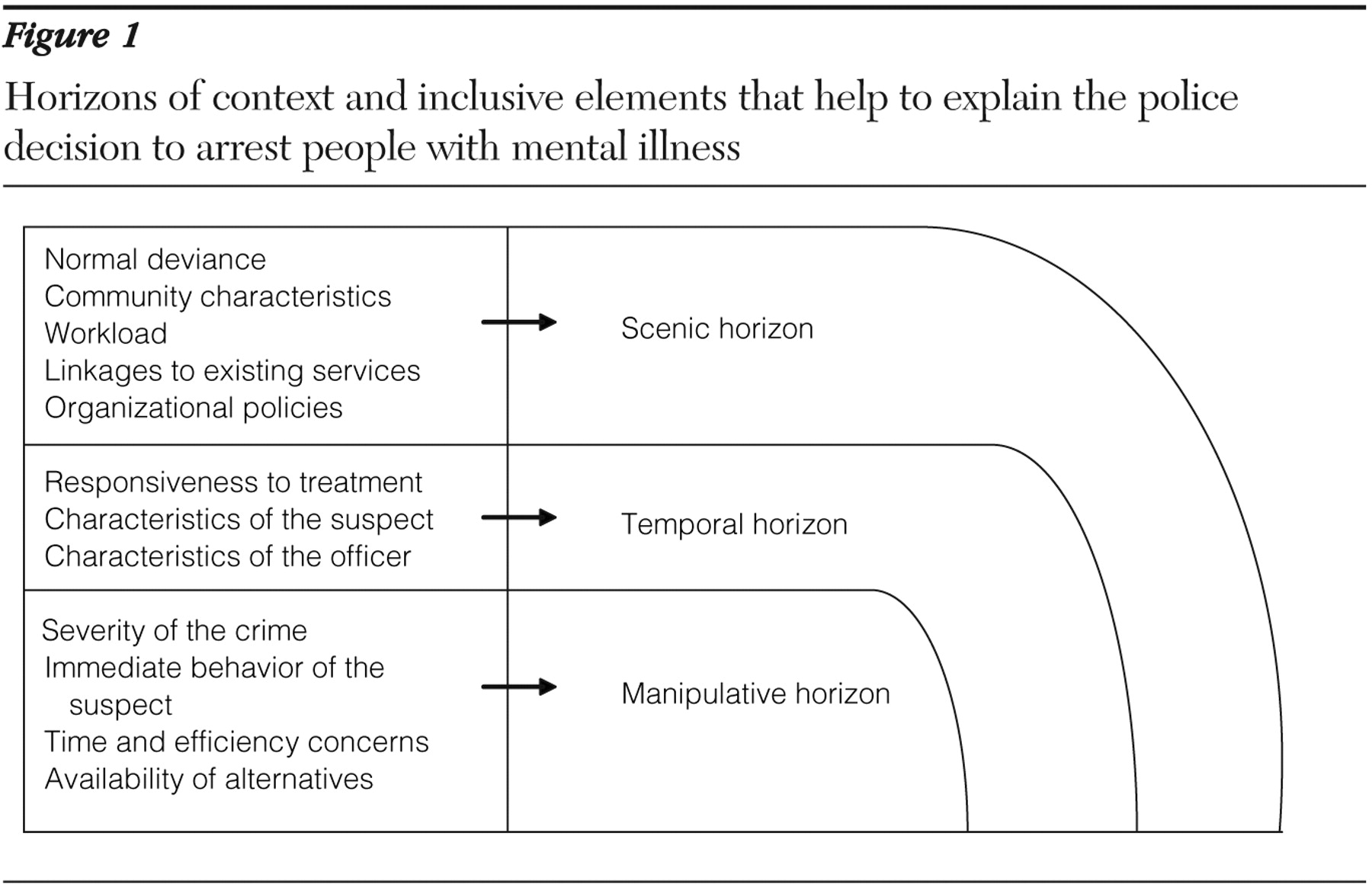

10 ). These horizons can also be used as a framework to explain the factors that influence the arrest decision. First, the scenic horizon is indicative of the features of the community. Second, the temporal horizon includes police knowledge that stretches beyond the specific incident and officer characteristics. Finally, the manipulative horizon involves the current incident from the standpoint of the officer and includes considerations of safety for the community as well as the immediate concerns of the officer. These horizons include the factors that typically influence police behavior during interactions with people with mental illness and are represented in

Figure 1 . The discussion of these three horizons that follows builds upon the work of Bittner (

10 ), and together these three horizons represent the framework from which police officers make decisions about the disposition of people with mental illness.

The scenic horizon

The criminal justice literature suggests that in order to understand the factors that influence arrest, it is not enough to consider only individual or incident characteristics (

21 ). Environment, although most often overlooked in the criminalization literature, is exceedingly important to understanding arrest, particularly because after deinstitutionalization, people with mental illness become more susceptible to neighborhood influences (

21 ). The scenic horizon is descriptive of the environment that can inform the police decision regarding the likelihood that an encounter with a person with mental illness can be controlled without arrest (

10 ). The scenic horizon includes five elements: normal deviance, community characteristics, organizational characteristics, workload, and linkages to community service.

Normal deviance implies that there is a baseline of disorder that the police and citizens are willing to accept. This baseline differs by community and is influenced by local norms and mores (

22 ). Community socioeconomic characteristics can explain police behavior in terms of arrest, crime, use of force, and police misconduct (

23,

24,

25 ). Although it has been suggested that people with mental illness may be arrested for sociostructural reasons (

1 ), these measures of neighborhood context are noticeably absent from the literature (

18 ). Specifically, measures of social disorganization, such as disadvantage and mobility, are relevant to understanding the police decision to arrest during encounters with people with mental illness (

26 ). Citizens residing in neighborhoods of varying levels of disadvantage rely upon police assistance differently. Because disadvantaged communities often lack structures of informal social control, they must rely heavily on the police to solve disputes (

27 ). This situation is further hampered by high levels of residential mobility, which often means that neighbors are less likely to help one another (

28,

29 ).

Police organizational characteristics can be descriptive of discretion at the administrative level (

29 ). Brown (

30 ) hypothesized that the discretionary choices of patrol officers are shaped not only by their own values and beliefs but also by the goals, incentives, and pressures of the bureaucracy. Police organizations are guided by both formal and informal mandates reflective of community preferences (

31,

32 ). Command staff, however, ultimately decide which neighborhoods and problems will receive the focus of the organization's resources through the deployment of officers and the provision of training (

33 )—two areas that may be key to enhancing the police response to people with mental illness (

9 ).

Another element that has been absent from previous studies of arrest is workload. In general, the busier a district is, the less likely it is that an arrest will be made (

22 ). Because the police patrol areas differently on the basis of existing levels of crime and disorder, workload can explain some police behavior and should be included in models that predict arrest. Finally, linkages to services in the community are also important for understanding police behavior, because officers who believe that the mental health system is ineffective are less likely to use it in the context of their work activities (

7,

34 ). Police may treat people with mental illness differently in communities where there are no mental health resources or where resources are perceived to be ineffective, compared with how they would treat them in communities that are perceived as having effective services (

11 ).

To illustrate the sometimes competing influences of the elements of scenic horizon, we can look at how they would affect the decision of the police in responding to a woman caught shoplifting $20 worth of food from a neighborhood deli. In this situation, the police consideration of normal deviance is based on the expectations of shop owners who want shoplifters prosecuted. The mayor has promised a crackdown on shoplifting to aid in the area's revitalization, which puts pressure on the officers to make an arrest.

The officers also patrol in a disorganized community, with pockets of high levels of poverty and residential mobility. The police have a high call volume and are eager to be back in service. Shoplifting $20 worth of food is a minor offense, so the officers may remove the woman from the store and release her with a warning not to shoplift again. Releasing the woman would allow the officers to return more quickly to the street to respond to other calls for service. Finally, the officers will consider linkages to community services. If officers know that the neighborhood is rich in services and have had good past experiences with the providers, they may decide to transport or refer the woman to one of the service providers, particularly given the eight-hour block of in-service training that one of the officers recently received regarding interacting with people with mental illness.

The temporal horizon

The temporal horizon is also largely ignored in the criminalization literature and involves police knowledge that stretches beyond the specific incident (

10 ), including the officer's own background and characteristics of the suspect, such as transience, substance abuse, and mental health needs (

35 ). Officer characteristics, such as age, gender, education, and experience, may be related to police behavior (

31 ). Officer mindset can also explain some of the arrest decision, because officers who are empathetic may be more likely to eschew arrest than their more cynical counterparts (

36 ). Furthermore, it is not unreasonable to suspect that there are police officers who have friends or relatives with mental illness, as it is estimated that between 5% and 20% of the population has a mental illness (

8 )—a factor that should be considered in mental health and criminal justice research.

Officers may also base decisions on the gender, race, or appearance of the suspect (

37,

38 ). Specifically, transience may affect police behavior (

39 ). King and Dunn (

39 ) concluded that the police may prefer to deal with troublesome persons in an informal manner, such as removing them from the city limits rather than invoking formal sanctions. Officer knowledge of substance abuse may also affect the likelihood of arrest. Because the possession of drugs is illegal and comes to the attention of the police, people with mental illness who are also substance abusers may first come into contact with the police because of illegal behaviors related to drug seeking, selling, and soliciting. This is particularly salient in understanding the interaction between the police and people with mental illness, because people with mental illness, particularly those with axis I disorders, have a high prevalence of substance use and abuse (

40 ).

The mental health needs of the suspect and his or her responsiveness to treatment can also explain police behavior. If the officer knows that the suspect has responded to treatment well in the past, an informal disposition may be more likely (

10 ). Mental health needs are also related to social support, a factor that may be considered in the decision to arrest, particularly when the suspect is impaired (

10 ). If an officer is aware of social support mechanisms, he or she may be comfortable with the existing linkages to services. In larger cities where police are likely to be unfamiliar with citizens, lack of knowledge about social support and service linkage may be a barrier to informal dispositions.

Returning to our earlier example can help us to understand the influence of the temporal horizon on the police decision to arrest. In this situation, the officers note that the woman caught shoplifting appears to be homeless, as evidenced by her belongings. It is possible that she is also mentally ill. One of the officers is particularly sympathetic to the difficulties of people with mental illness, because he has a brother with a schizophrenia diagnosis. His inclination is to try to link the woman with services rather than arrest her. This officer has five years of patrol experience and has interacted with the woman before in another incident, and in that situation the woman appeared calm. He has no prior knowledge, however, of how she may respond to treatment or whether she has a support network in place, but he does know that she often sleeps in a nearby park. She does not appear to have any family in the neighborhood—meaning that she is lacking both social support and a fixed address.

The manipulative horizon

The manipulative horizon is the set of factors most commonly included in studies of people with mental illness and includes considerations of safety for the community as well as the immediate concerns of the officer. The elements included in this horizon are largely based on the immediate situation (

10,

22 ). The manipulative horizon includes the severity of the offense, immediate behavior, time and efficiency concerns, and the availability of alternative resources.

First, officers must consider the type of crime committed; the more severe the offense, the less discretion an officer can employ (

27,

41 ), because serious crime is associated with victims who want to press charges, media attention, and political scrutiny. As a result, officers will have little discretion if a person is suspected of committing a serious crime, regardless of his or her mental health status (

3 ). Officers also consider the relationship between the victim and the suspect, the preferences of the victim (

42 ), and the use of a weapon (

18 ). If victims want the police to exercise leniency, the officer will usually respect these wishes (

27 ).

Next, officers will examine the immediate behavior of the suspect. Troublesome behavior resulting from drug use or psychiatric symptoms can bring people with mental illness to the attention of the police (

2 ). It may not, however, shape the encounter or be predictive of arrest (

31 ). Frequently in the police literature, immediate behavior in police interactions is operationalized by a measure of resistance (

19,

37 ). The probability of arrest increases when a suspect is disrespectful to the police (

27 ) or displays extreme hostility (

22 ). Resistance should be included in any model of police behavior, because recent studies indicate that people with mental illness may be more disrespectful to the police, compared with their counterparts without such an illness (

19 ).

The police literature suggests that the amount of discretionary time an officer has is crucial to understanding police behavior (

7,

43 ). Taking someone for psychiatric help at a hospital has been described as "a tedious, cumbersome and uncertain procedure" (

10,

44 ). When officers respond to an incident, they are considered to be out of service. Taking a citizen for psychiatric help at a hospital may present a hurdle for police officers who may be pressured to return to in-service status so that they can respond to calls from the community. In most localities, an arrest takes substantially less time to process than an involuntary hospitalization (

45 ). No action or an informal disposition can take less time than a hospital transport or even arrest. If, however, the officers have an available alternative that they have found to be efficient (

34 ), it may be the better choice. Police may prefer to bring a person with mental illness for assistance over arrest if given the opportunity (

46 ).

To finish our example including the elements of the manipulative horizon, we can see that the severity of crime, immediate behavior, and the time and efficiency concerns will affect the final decision made by the police. In this scenario, the suspect has shoplifted items worth only a small amount. If she also was harassing customers, this might limit the officers' discretion. In this situation, however, the store owner does not want to press charges because the merchandise has been returned. The woman does not have a weapon, and although she is clearly exhibiting troublesome behavior, she has not shown any resistance. In the part of the city where this incident has taken place, there is also an available psychiatric emergency room where the police know that they can quickly get the woman help without getting backed up on calls. Given the entirety of factors that describe this situation, the officers are likely to bring the woman to the psychiatric emergency room or let her go with a warning rather than make an arrest. The officers will then be able to return to in-service status and respond to other calls in the community.

To summarize, the decision to arrest is cumulatively affected by three sets of factors: scenic, temporal, and manipulative. In this example, the police were heavily influenced by the disorganization of the community and resulting workload, coupled with the severity of the crime and the preference of the victim. The factors are listed in

Figure 1 .