Identification of assault motivation

Narrative description of assault. Using the SIR electronic database, we collected for further investigation the specific date and time that each of the study participants committed assaults. The corresponding narrative description was then located in the patient's medical record. The first step involved reviewing the description of the aggressive act as documented in the incident report. These reports are filed in the interdisciplinary notes, which are daily records of observations and treatment provided to patients by nursing staff. After reviewing the report, we checked interdisciplinary notes written in the days preceding and following the assault in order to gain additional information regarding the assault. We often found that a review of the events leading up to the assault, the clinical management of the incident, and the statements made by an assailant after the assault was very useful in providing the level of detail required to categorize an assault when the incident report was lacking in detail. It was not uncommon for assailants to disclose their reasons for an assault hours or even days after the incident.

Assault categorization. The narrative was used to categorize assaults as impulsive, organized, or psychotic by using a modified version of a procedure for classifying aggressive acts through the use of formal records. The procedure was originally developed by Stanford and Barratt (

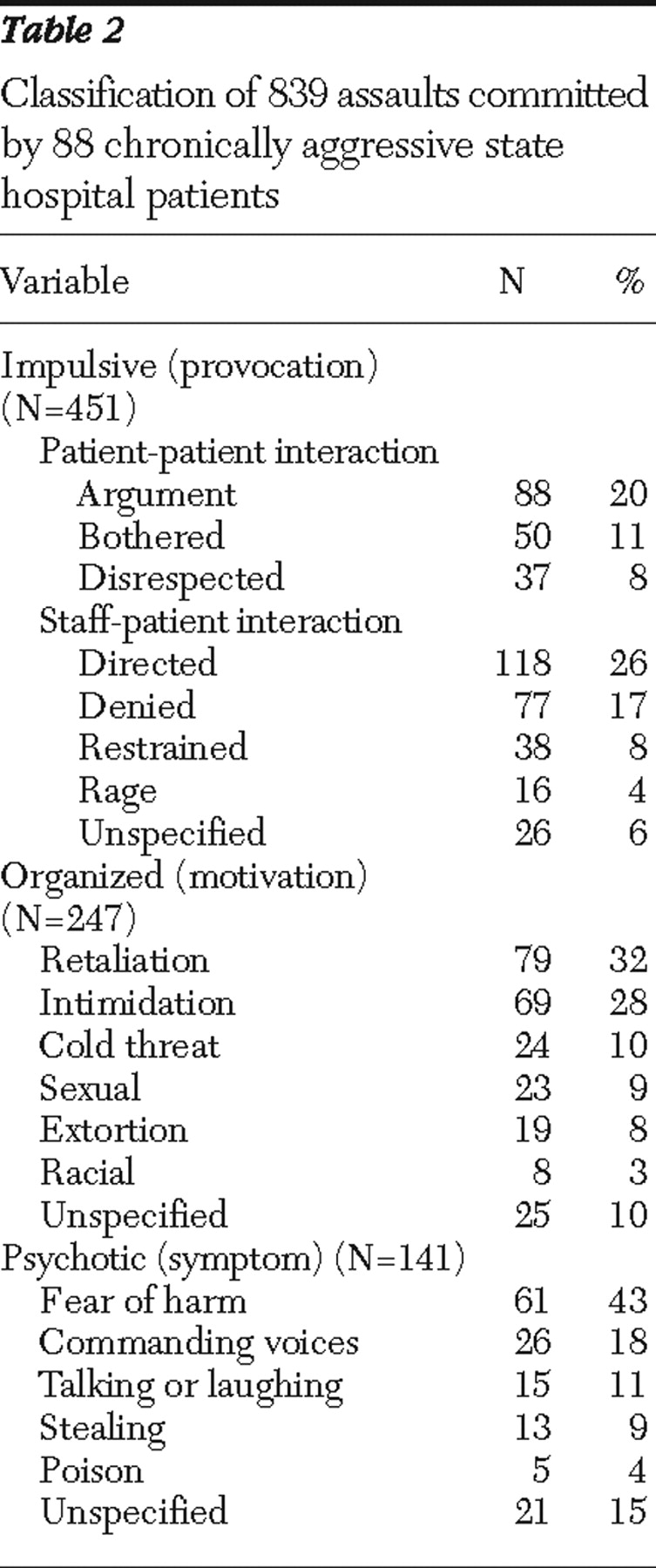

29 ) by using descriptions of assaults by prisoners contained in disciplinary reports. Impulsive assaults had the following characteristics: an identifiable, immediate provocation, agitated or out-of-control behavior (for example, pacing, anger, hostility, or yelling), verbal threats, failed attempts to calm the patient, lack of concern about consequences of the act or personal safety, no obvious secondary gain or long-term motive, or expressions of remorse after the incident. Organized assaults had the following characteristics: proactive or involved some degree of planning, unprovoked or minimal provocation, a social motive (for example, asserting dominance) or an external goal, use of a weapon, preceded by little warning or came as a surprise, an absence of agitation from the patient or an appearance of being in control of his or her behavior, or denial of the assault after the event. Psychotic assaults also were unprovoked; however, the attack lacked a rational alternative motive, and the assailant cited a symptom (delusion or hallucination) as the reason for committing the assault. In addition, evidence of psychosis was present before and after the assault.

If the information contained in the narrative description of the aggressive incident was not sufficient to classify a motivation for the assault, we attempted to gain further information by reviewing additional records (for example, treatment team conferences) and through behavioral consultations (for example, a psychological investigation into reasons for assaultive behavior and treatment recommendations). Assaults without a sufficient description to determine a motivation were coded "unable to determine."

Assault subcategorization. For all assaults categorized, we attempted to further subcategorize impulsive assaults by the provocation preceding the assault. We also organized assaults by the motive and organized psychotic assaults by the symptom driving the assault.

Provocations to impulsive assaults. Impulsive assaults occurred after an adverse interpersonal interaction with either a staff member or another patient. Seven subcategories were defined: directed, denied, restrained, rage, argument, disrespected, and bothered. Interactions with a staff member leading to assault of the staff member were broken down into the two subcategories: directed, a patient assaults the staff member after the staff member directs a patient to stop an unwanted behavior or start an activity, and denied, the patient assaults the staff member after the staff member refuses a patient's request. In addition, we created two other subcategories that involved interactions with a staff member leading to assault, but the victim was not the staff member who initially provoked the patient: restrained, a staff member is assaulted in the process of placing an agitated patient into seclusion or restraints; and rage, an agitated patient assaults a bystander patient who is in the vicinity but played no role in provoking the patient.

Impulsive assaults occurring after an adverse interpersonal interaction with another patient were broken down into three subcategories: argument, a patient assaults in the context of an argument that began verbally but escalated into physical violence with the assailant initiating the violence; disrespected, a patient assaults after the victim insults the assailant (for example, name calling) or makes statements that the assailant feels are disrespectful; and bothered, a patient assaults a victim whose behavior is perceived as bothering or irritating to the assailant (for example, following too closely, invading personal space, or talking or yelling incessantly).

Motives for organized assaults. Assaults with an organized motivation were subcategorized by the motive or goal for the aggressive behavior. Six subcategories were identified: retaliation, intimidation, extortion, cold threat, racial, and sexual. In the first subcategory, retaliation, a patient feels that he or she has been wronged and thus assaults in order to get even or exact revenge—for example, to settle a score. Second, with intimidation a patient assaults in order to assert his or her dominance over another individual, for example, bullying behavior. Third, with extortion a patient uses actual or threatened force in an attempt to obtain from another patient a desired item—for example, cigarettes, food, or money—to which the patient is not entitled. Fourth, with cold threat a patient implies that he or she will harm the victim at a future point if the victim does not comply with a request—for example, a patient calmly tells a nurse to "watch your back tomorrow" after a request for benzodiazepine is refused. Fifth, with racial motivation the patient assaults because the victim is a member of a particular ethnic group. And finally, with sexual motivation a patient behaves in a sexually aggressive manner toward another—for example, grabbing or making sexually inappropriate comments.

Symptoms motivating psychotic assaults. We identified five subcategories of assault motivated by psychotic symptoms: beliefs of harm, stealing, poisoning, talking or laughing, and commanding voices. These predominantly involved assaults in which the assailant acted under the influence of a paranoid idea or misinterpretation. With belief of harm as the psychotic symptom, a patient assaults a victim acting under the belief that the victim has harmed or is planning to physically harm the patient. With stealing as the psychotic symptom, a patient assaults a victim because he or she believes that the victim stole from him or her. With belief of poisoning as the psychotic symptom, a patient assaults a victim who is believed to be poisoning him or her—for example, via food or medications. With belief of talking or laughing as the psychotic symptom, a patient assaults a victim believed to be laughing at him or her or talking about him or her in a negative way. Another subcategory, belief of commanding voices, was used when a patient displaying signs of psychotic disorganization (disordered thought and speech or responding to internal stimuli) assaulted a victim without provocation and may have reported commanding auditory hallucinations to assault.

Some assault descriptions contained sufficient information to categorize a motivation, but there was not enough to subcategorize the assault. Alternatively, some assaults did not clearly fall into a particular subcategory. These assaults were coded as unspecified.