Parent and child characteristics

Of the 26 parents, 22 (85%) were the child's biological parent and 20 (77%) were mothers. The four nonbiological primary caregivers (15%) were referred to as parents. Family history of psychiatric illness was present for 14 parents (54%) and included substance abuse (ten parents, or 38%), ADHD (six parents, or 23%), learning disorders (five parents, or 19%), and depression (three parents, or 12%).

The average child's age was nine years, 17 (65%) were boys, and 25 (96%) were African American. Of the 15 children (58%) with an axis I diagnosis in addition to ADHD, six had adjustment disorders (23%) and six had learning disorders (23%).

Conceptualization of child behaviors

Seven themes emerged from the retrospective histories of how parents came to seek medical care for their child. These were descriptions of the behavior, placing the behavior in context, making sense of the behavior, seeing the effect of the behavior, approaches to seeking information, managing the behavior, and parents' vision for their child. The relationship among themes described the interactive phases of identification, understanding, and acceptance as parents came to terms with their child's ADHD. Family and school situations affected how parents moved through each phase. The time from when parents first noted the behavior until they sought professional care ranged from less than one year to four years.

Identification. Many parents identified their child's behavior as out of context for what was expected of peers their child's age. They described their child as inattentive, unfocused, distractible, and in their own words, "a speeding robot," "got to get their run out," or "very out of control." One noted, "I just knew I didn't have these problems with my two older children." Others described a threshold, "people tear things up, but it's to a degree where his is not normal, it's not like the normal kind of breakage." For one it was emotional, "I don't think he should feel the way he does, which hurts me more." When children "seemed normal" to parents, it was often teachers, clinicians, family, or friends who noted the behaviors.

Understanding. Parents reflected on what caused the behaviors, how their child was affected, and how they could get answers as they developed an understanding. Behaviors were attributed to genetics, a medical condition, child development, or just "something within her." Prenatal drug or alcohol use, lead exposure, or early parenting practices also were thought to contribute to the behaviors. Some parents questioned how the behaviors developed. Many saw the problems affecting their child's academic performance and inability to control his or her behavior and follow directions. There also was difficulty in the child's getting along with family. For example, "Sometimes it would really work my nerves a little bit. … It can be very, very frustrating," or "A lot of times, I need a timeout." Or it interfered with home life: "It's just gotten worse. … I see him withdrawing from us. … He gets very angry, he acts out, and then he doesn't want to do things with me that he used to." A few noted emotional problems or low self-esteem as children saw how the behaviors affected their lives. Family disagreement about management strategies influenced when and from whom parents sought help. As one mother noted, "I would never come to him and say, 'Dad, I think he does have a problem,' because he's like 'oh no, there's no way in the world that he has a problem, he's just a boy.' " Some needed reassurance: "If there wasn't anything wrong, then I don't understand why he is the way he is, because then I would feel that it was something that my husband and I are lacking in as parents—that we're not doing right."

Acceptance. Eventually, parents accepted management strategies and discussed future goals. Most mentioned disciplinary changes or assistance with homework. Some sacrificed their own goals: "I took a year off of school. I haven't been to school since spring of last semester just so I can sit down with him every day and help him." Parents also discussed support programs or child recreational activities. Others did not do anything different or felt the school needed to make accommodations for their child's behavior. Some were reluctant: "I was kind of embarrassed because … I don't really want to feel that he needs help." Future goals focused mainly on academic success. Some longed for more basic things; for example, "I just want to be able to go shopping with her." Personal reflections included "I want him to have a better life than I had." Other parents characterized this as a phase, such as "Someday we will look back on this and say, 'remember when.' " Long-term outlooks included "I want him to be the best that he can be" or "I hope this won't affect his chances to get into college or get a job." Some realized the possibility of persistence into adulthood: "I'm hoping that he will be able to manage this without medication."

Coming to terms with ADHD

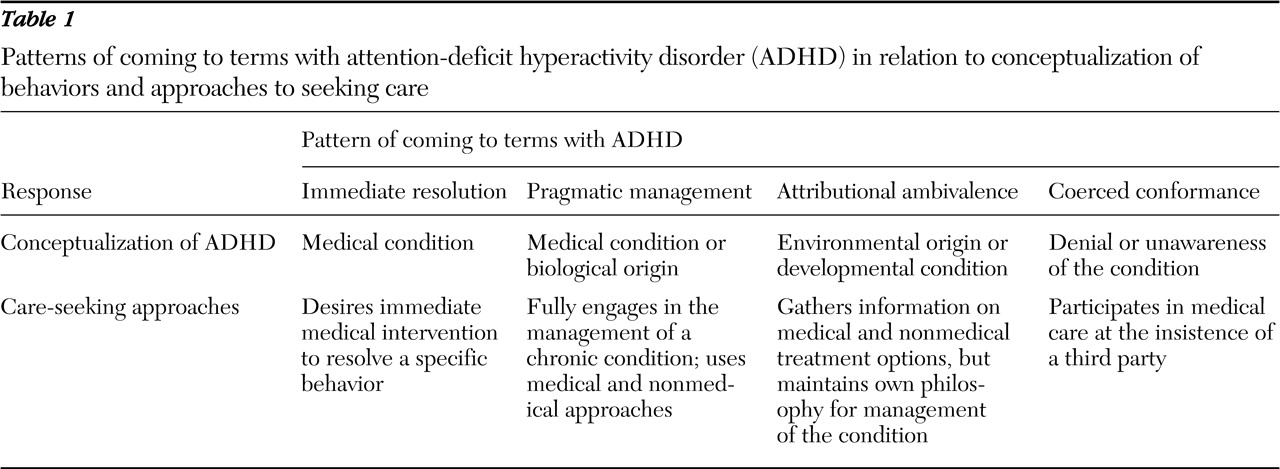

Four distinct patterns emerged that were based on how parents experienced the phases of identification, understanding, and acceptance. These patterns of coming to terms with ADHD were immediate resolution, pragmatic management, attributional ambivalence, and coerced conformance. Each participant was classified into only one pattern, as follows: ten (38%) used immediate resolution, eight (31%) used pragmatic management, two (8%) fit the pattern for attributional ambivalence, and six (23%) were classified as coerced conformance. Despite some overlap in how parents worked through each phase, each pattern had its own distinguishing characteristics (

Table 1 ).

Immediate resolution. The immediate resolution pattern comprised parents whose main interest was finding a solution for the problematic behaviors. Child behaviors were viewed as ADHD symptoms, and ADHD was understood to be a medical condition interfering with academic performance and social relationships. Parents were eager for a medical resolution to the current problems. Some parents took longer to accept the situation because they initially thought that the behaviors were caused by a coexisting psychiatric disorder or because they had unfavorable experiences with a family member's psychiatric illness or psychotropic treatment.

Pragmatic management. Parents who fit the pragmatic management pattern viewed the behaviors as ADHD symptoms that were a medical or biological disorder with long-term consequences that they had to manage. They addressed the problems directly by seeking multiple types of help, including medical care. They described their child's behavior as the core ADHD symptoms and noted this was not typical of peers of similar age. They understood that ADHD was affecting their child academically and socially, and unlike parents using immediate resolution, this group's long-term views resulted in their learning about and engaging in medical and nonmedical interventions for managing ADHD.

Attributional ambivalence. The attributional ambivalence pattern was characterized by individuals who viewed their child's behaviors as problematic and atypical for children of similar age, but they did not necessarily describe the behaviors as symptoms of ADHD. They believed that the behaviors were caused by environmental or nonbiological factors or were related to other emotional problems that their child was experiencing. Primary concerns were the child's academic progress and emotional stability. Acceptance focused on religious beliefs or disciplinary tactics rather than medical interventions to manage the situation. Their process of coming to terms with the diagnosis was to gain information about treatment options, but they maintained a strong emphasis on their own philosophical approach to the problem.

Coerced conformance. These parents came to terms with the need to seek medical care for their child's problems but not actually with their child's ADHD. Parents whose process was one of coerced conformance endorsed theoretically opposing qualities relative to the other groups. These parents did not perceive the behaviors as problematic, did not conceptualize them as indications of an illness, and did not endorse specific strategies for short- or long-term management. Instead, their actions were motivated through the instigation of a third party, commonly the child's school.