The only previous study that has attempted to determine an adjusted prevalence of HIV among persons with serious mental illness used Philadelphia Medicaid claims data from fiscal years 1994–1996 (

13 ). The study found that compared with persons who did not have a mental disorder, those who had major affective disorders had 3.8 times the adjusted odds of having HIV and those with schizophrenia had 1.5 times the odds (

13 ). Although this study controlled for age, race, ethnicity, and length of time on welfare, it did not adjust for substance use or marital status. Descriptive studies have indicated that individuals with serious mental illness may be at risk for HIV as a consequence of substance use disorder and of high-risk sexual behaviors (

12,

14,

15,

16 ). Previous studies have demonstrated that both substance use disorder and marital status are strong independent risk factors associated with HIV infection in the general population (

17,

18 ). Thus it is important to understand the influence of these factors on overall HIV risk among individuals with serious mental illness.

The goal of this study was to determine the recorded prevalence of HIV in a national population of patients with serious mental illness receiving care from Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities and compare it with the prevalence in a national random sample of VA patients who did not have serious mental illness. This approach had two important strengths. First, having a large national sample of individuals with serious mental illness allowed us to overcome methodological limitations of previous studies—small samples and region-specific convenience samples—making it possible to generate more precise prevalence estimates. Second, having a comparison group of a random sample of VA patients who did not have diagnoses of serious mental illness allowed us to adjust for important HIV-related risk factors in order to more clearly understand the relationship between the diagnosis of serious mental illness and HIV.

Discussion

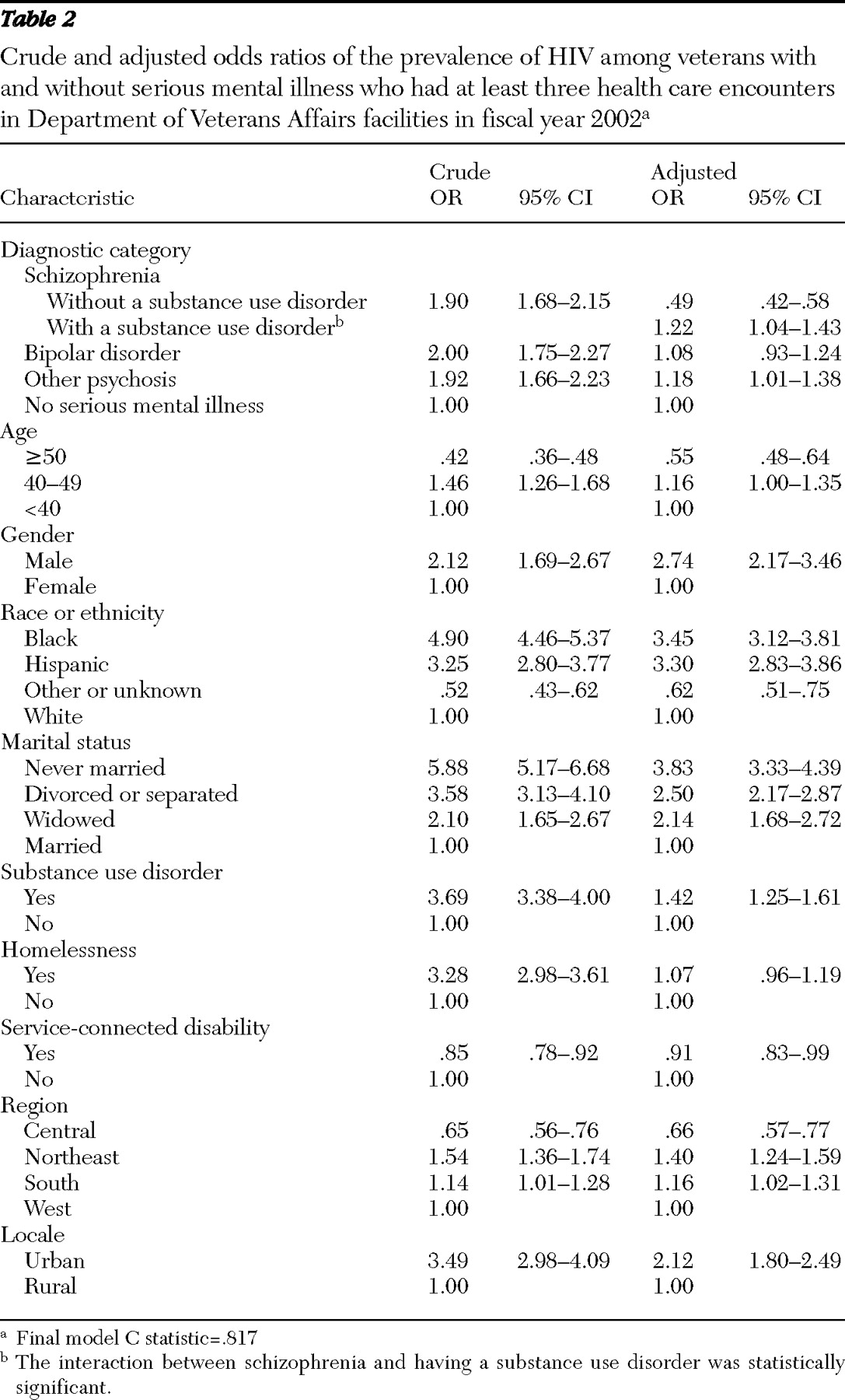

Among a national population of VA patients, we found that the crude odds of having an HIV diagnosis were twice as high among patients who had diagnoses of serious mental illness as among patients who did not have serious mental illness diagnoses. This relationship was observed overall and by diagnostic subgroup of serious mental illness. This finding is consistent with results of many previous studies that have found elevated rates of HIV among individuals with serious mental illness. Although the recorded prevalence of HIV among those with serious mental illness in our study was lower than that in previous studies, an important strength of our findings is that they are based on a national sample of individuals with serious mental illness. As a result, our findings may not be subject to the biases associated with convenience samples or differences in sampling frames. Our results are also consistent with results of a previous study that used administrative data; this study found that the crude period prevalence of HIV was approximately twice as high among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia as among beneficiaries without serious mental illness (

13 ).

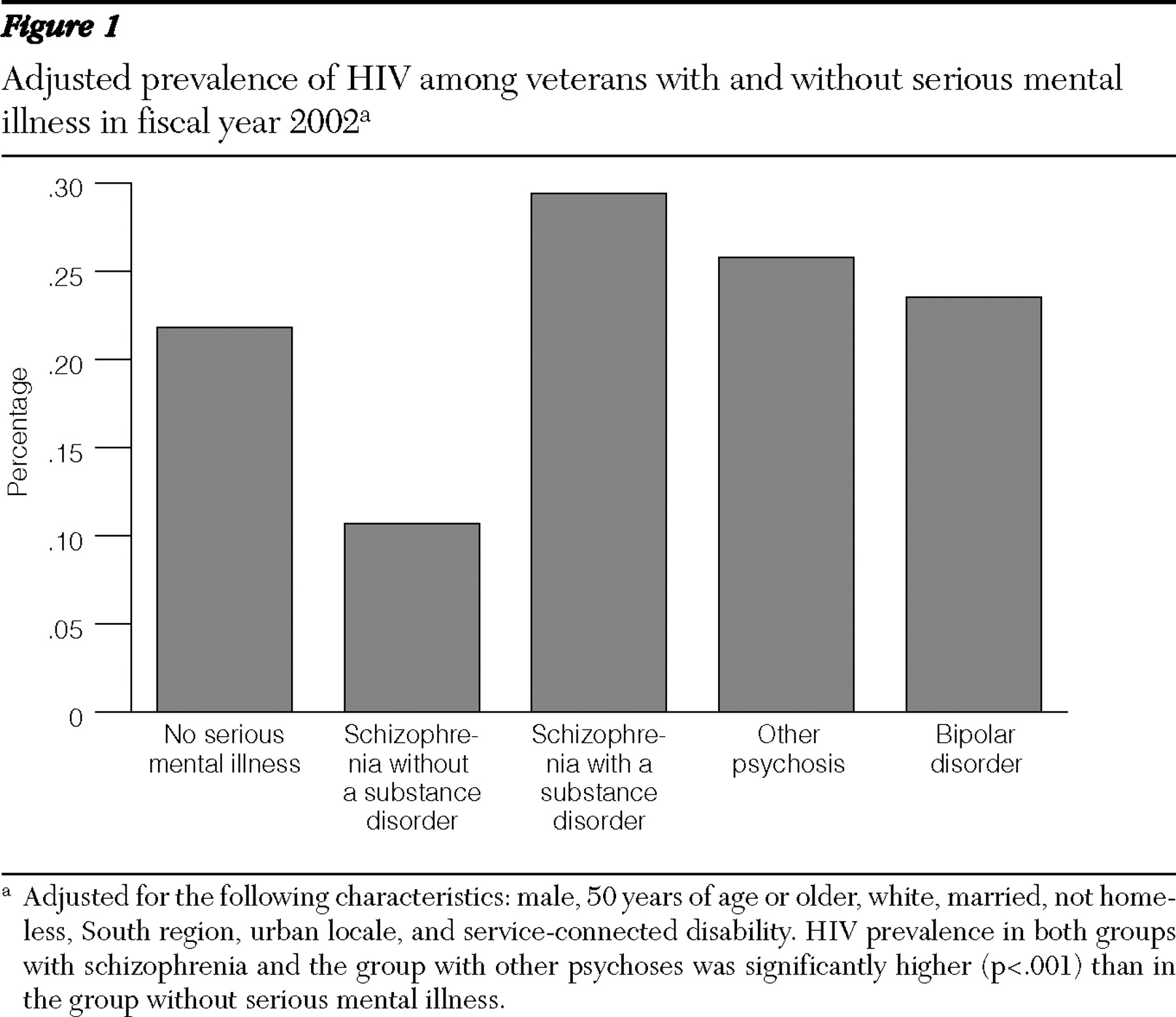

In addition, we found that adjusting for HIV risk factors and demographic characteristics considerably reduced—and even inverted—the association between diagnostic subgroups of serious mental illness and HIV. Specifically, we found that after the analyses adjusted for HIV risk factors and demographic characteristics, patients with bipolar disorder were as likely to have a diagnosis of HIV as those without serious mental illness and that those with other psychoses were 18% more likely. This considerable reduction in the association between serious mental illness diagnoses and HIV highlights the importance of adjusting for risk factors associated with HIV. This is most clearly the case for individuals with schizophrenia, among whom we found a significant interaction between substance use disorder and schizophrenia diagnosis. Specifically, compared with patients who did not have serious mental illness, those with co-occurring schizophrenia and a substance use disorder were 22% more likely to have HIV and those with schizophrenia who did not have a co-occurring substance use disorder were 50% less likely to have HIV. In other words, not having a substance use disorder appears to be protective among persons with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Previous studies suggest that people with schizophrenia tend to have lower overall rates of sexual activity than the general population (

12 ), which may highlight the impact that substance use has on the risk of contracting HIV and on engaging in high-risk sexual behavior. Alternatively, some studies suggest that among persons with schizophrenia, those with substance use disorders have fewer negative symptoms than those without substance use disorders (

29,

30 ). Thus it is possible that negative symptoms, such as apathy, decreased sociability, and poverty of speech, may in fact be the moderating factor accounting for our finding that patients with schizophrenia who did not have a substance use disorder were significantly less likely to be infected with HIV.

Alternatively, our finding that patients with schizophrenia without a co-occurring substance use disorder were less likely to have an HIV diagnosis may be the result of underdiagnosis or undercoding of HIV diagnoses. Although worsening psychotic symptoms may be a barrier to receiving HIV testing, a study by Desai and Rosenheck (

31 ) found that among a cohort of homeless individuals with serious mental illness who were enrolled in a case management program, the likelihood of being tested for HIV was independently associated with more severe psychiatric symptoms. Finally, because persons with schizophrenia and a co-occurring substance use disorder are more likely to be at greater risk of not using medical services, we believe we probably underestimated, rather than overestimated, the effect of the interaction—that is, patients with schizophrenia and a co-occurring substance use disorder are likely to be at even greater risk for HIV infection.

It is particularly noteworthy that the relative odds of HIV among individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and a co-occurring substance use disorder were substantially lower in the adjusted model, which is consistent with the lower rates we found in the adjusted model for those with bipolar disorder and for those with other psychoses.

We also found that risk factors associated with HIV in our study were consistent with those that have been reported for the general population (

32 ) and for VA samples (

33 ). First, the prevalence of HIV in the control group without serious mental illness in our study is consistent with the prevalence of HIV of .5% reported by the VA Immunology Case Registry in FY2002 (

33 ). Our sample was similar to the VA Immunology Case Registry, in that it was predominantly male and older than the general non-VA population.

Second, we found that being male, black or Hispanic, and unmarried, having a diagnosis of a substance use disorder, and receiving services in an urban setting were associated with a greater risk of HIV. Although homelessness was positively associated in the crude analysis with having an HIV diagnosis, it was no longer significant after the analysis adjusted for a diagnosis of serious mental illness and a co-occurring substance use disorder. This may reflect the positive associations between being homeless and having a severe mental illness (

34 ). HIV has been noted to be particularly endemic in urban locales in the coastal regions of the United States, and thus it is not surprising that those who received services in the Central region were significantly less likely to have HIV.

The study had some limitations. First, because it is cross-sectional, we cannot make strong claims about the direction of causation. Although HIV may cause people to have depressive and psychotic symptoms (

35 ), research suggests that in most cases, psychotic disorders precede HIV infection (

36 ). Second, the study was limited by factors associated with using administrative data sets. Because substance use disorders are frequently underdiagnosed, it is possible that we underestimated the frequency of these disorders in the sample. It is also possible that we underestimated the prevalence of HIV, because diagnosis data in administrative data sets may not fully identify individuals with HIV who are not actively engaged in HIV treatment or who may choose to receive that treatment from a non-VA provider.

We attempted to decrease the likelihood of this limitation by restricting our analysis to individuals with at least three health care visits during FY2002. Compared with those with three or more visits, those with two or fewer visits were significantly more likely to be female, to have no race recorded, and to be married; they were less likely to have an indication of homelessness, a substance use disorder, or a service-connected disability. By limiting the analysis of HIV prevalence to patients with at least three VA encounters in FY2002, we excluded patients who may have received most of their care (and illness diagnoses) from non-VA providers. Patients with fewer than three encounters or with none at all had fewer or no opportunities to have had HIV diagnoses recorded in the VA data in FY2002. Finally, we were unable to distinguish receipt of an HIV diagnosis from receipt of an HIV diagnosis as a part of HIV treatment management in this sample (Bowman C, HIV Query Group, personal communication, May 2006).

Third, because the results of this study are based on data from veterans who were receiving care in VA facilities, it is unclear to what extent the results may be generalized to veterans who are infrequent users of VA services or to the nonveteran population. Rosenheck and colleagues (

37 ), using data from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) and data from the VA extension of the PORT, compared the treatment of schizophrenia in VA and non-VA clinics and found that persons with schizophrenia treated in VA clinics were more likely to be male and older and to have higher incomes but were no different in race, marital status, or education than persons with schizophrenia treated in non-VA clinical settings. They also reported no differences with respect to alcohol or substance use, incarceration, symptom distress, satisfaction with providers, and community adjustment compared with individuals with schizophrenia who were receiving care in non-VA clinics. They did note that those receiving care in the VA system were less likely to use community-based psychosocial treatment and more likely to rely on hospital treatment than non-VA patients. Young and colleagues (

38 ) compared a random sample of outpatients with schizophrenia at a VA facility in California with a random sample of outpatients with schizophrenia at a regional mental health clinic in California. They found that VA patients were more likely to be older and male and to have higher incomes.

Although we did not have information on age of onset of symptoms, it appears that patients with schizophrenia in treatment may not differ in social functioning compared with those receiving non-VA services (

37 ). Although the VA may be the provider of last resort for veterans without serious mental illness, it is unclear whether this is the case for individuals with serious mental illness (

37 ). Finally, because some patients may use two systems of care—that is, Medicare and VA services—it is possible that our results are biased because we were unable to capture medical service use in other systems of care. Further research is necessary to clarify this issue.

Fourth, we did not have specific variables to adjust for the mediating roles of injection drug use and high-risk sexual behavior, which are known to be causally linked with serious mental illness and transmission of HIV. Instead, we used the more distal variables of substance use disorder and marital status to account for these risk factors. We used these variables, as have previous studies (

17,

18 ), because it is difficult to obtain reliable estimates of stigmatized behavior, such as high-risk sexual behavior. However, our analysis indicates that these proxy measures were strongly associated with HIV diagnosis, and therefore we believe they served as reasonable alternatives.

Fifth, if the observed differences in age between the group with serious mental illness and the control group were related to differential early mortality from HIV, we may have underestimated the prevalence of HIV among patients with serious mental illness. However, sensitivity analyses showed that the serious mental illness group in fact had a higher prevalence of HIV in the older age groups than did the control group without serious mental illness. If differential mortality from HIV were associated with the observed age difference, the trend would be the reverse, with higher prevalence among those with serious mental illness at younger ages.

Sixth, although the absolute difference in the adjusted probabilities of having a recorded HIV diagnosis is small, on a population level the difference would represent a considerable reduction and would likely have considerable clinical merit. Seventh, information about the frequency of HIV testing in the VA system of care is currently not published. However, the VA's policy (

39 ) is to "urge all VA providers to make risk assessment and testing for HIV, sexually transmitted diseases, and other chronic viral infections a routine part of medical care." Finally, several reports suggest that there is acceptable concordance between VA administrative data and medical record data (

25,

26,

27 ).