The 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was associated with significant emotional distress in 18% to 57% of health care workers during and shortly after the outbreak period (

1,

2,

3,

4,

5 ). Less information is available about the longer-term impact of health care work during the SARS outbreak. The Impact of SARS Study found that one to two years after the outbreak, professional burnout and symptoms of traumatic stress, anxiety, and depression remained somewhat elevated among Toronto hospital workers compared with colleagues in settings that did not treat SARS patients (

6 ). A key question about this finding is whether persistent post-SARS elevation of distress among some health care workers interferes with their social and occupational function. Distress is normative; however, in rare instances, a psychiatric disorder is diagnosed when psychological distress persists over time and interferes with social and occupational function (

7 ).

Working in a hospital during the SARS outbreak may have represented a psychological trauma for some health care workers. Typically, 80% to 90% of people exposed to trauma do not develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (

8 ). However, several factors may have increased the perceived personal risk associated with SARS (

9 ), including the uncertainty of dealing with an illness of unknown cause and mode of transmission before the identification of the SARS coronavirus (

10,

11,

12,

13 ) and the disease's rapid global spread and significant mortality.

Understanding the psychiatric impact of SARS on hospital workers in terms of both distress and disorder is relevant to the well-being of large numbers of exposed health care workers who continue to work in their profession and who could be at risk of exposure to future emerging infections, including pandemic influenza (

14 ). In our previous study, we measured distress in a large sample of health care workers (

6 ). In the study reported here, we investigated disorders, as reflected by the prevalence of PTSD and other psychiatric diagnoses, among workers at SARS-affected hospitals one to two years after the resolution of the SARS outbreak. We tested the hypothesis that new episodes of psychiatric disorders after SARS would be more frequent among health care workers who had a history of psychiatric illness. In the previous analysis of distress (

6 ), we found that having more years of health care experience and an individual's perception of having had adequate training were protective. Therefore, we also tested the hypothesis that these variables would protect against new episodes of psychiatric disorders, beyond the impact of a history of psychiatric illness.

Methods

The Impact of SARS Study was conducted in Toronto and in Hamilton, Canada, between October 23, 2004, and September 30, 2005. This report concerns the health care workers in Toronto, where almost all of Canada's 438 suspected and probable SARS patients were identified. All nine of the academic and community hospitals in Toronto that participated in this study treated SARS patients. Eligible health care workers included nurses in medical or surgical inpatient units and all staff of intensive care units, emergency departments, and SARS isolation units. This study was approved by the research ethics boards of each hospital. After participants were given a complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained.

Of the 587 Toronto participants who completed several self-report outcome scales in part 1 of the Impact of SARS Study (

6 ), 139 (24%) volunteered to participate in a diagnostic interview and were given the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS). Of these, 133 (23% of the overall sample) also participated in a SCID interview. Interviewed individuals received $50.

Survey questionnaires included the 15-item version of the Impact of Events Scale (IES) (

15,

16 ), the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) (

17 ), the emotional exhaustion scale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (

18,

19,

20 ), and self-report of any increase since the SARS outbreak in smoking, drinking alcoholic beverages, using nonprescription drugs, or "other activities that could interfere with your work or relationships." Perception of the adequacy of training, protection, and support with respect to SARS was measured by using a previously described instrument (

5,

21,

22 ).

Axis I diagnoses were determined with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (

23,

24,

25 ), excluding the psychosis and PTSD modules, which was administered by trained interviewers. For each endorsed disorder, the interviewer determined whether symptoms preceded SARS, followed SARS, or both and whether the symptoms were present in the past month.

The PTSD section of the SCID was replaced with the CAPS (

26,

27 ). The CAPS is a structured interview that assesses PTSD diagnostic status and symptom severity. The CAPS has excellent reliability (greater than the SCID), yielding consistent scores across items, raters, and testing occasions (

28 ). There is also strong evidence of convergent and discriminant validity, diagnostic utility, and sensitivity to clinical change. The CAPS was administered one or two times: first, for the most severe past trauma of any kind (including SARS as a candidate event) and second, for the most recent trauma if it was different from the most severe past trauma assessed in the first administration. For each of the one or two events, symptoms were placed in two time frames: ever since the trauma and in the past month.

We determined the prevalence of lifetime axis I psychiatric disorders before the SARS outbreak. The prevalence of new episodes of a psychiatric disorder was determined and compared among participants with or without a previous episode of a psychiatric disorder. Because panic attacks were frequently reported by the health care workers in this study even in the absence of panic disorder, the prevalence of post-SARS panic attacks was also compared among participants with or without a previous episode of a psychiatric disorder.

Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the contributions of previous episodes of a psychiatric disorder, perception of adequate training and support, and years of health care experience to the occurrence of a new episode of a psychiatric disorder post-SARS. A two-tailed test of probability with p less than .05 indicated statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS, version 15.0.

Results

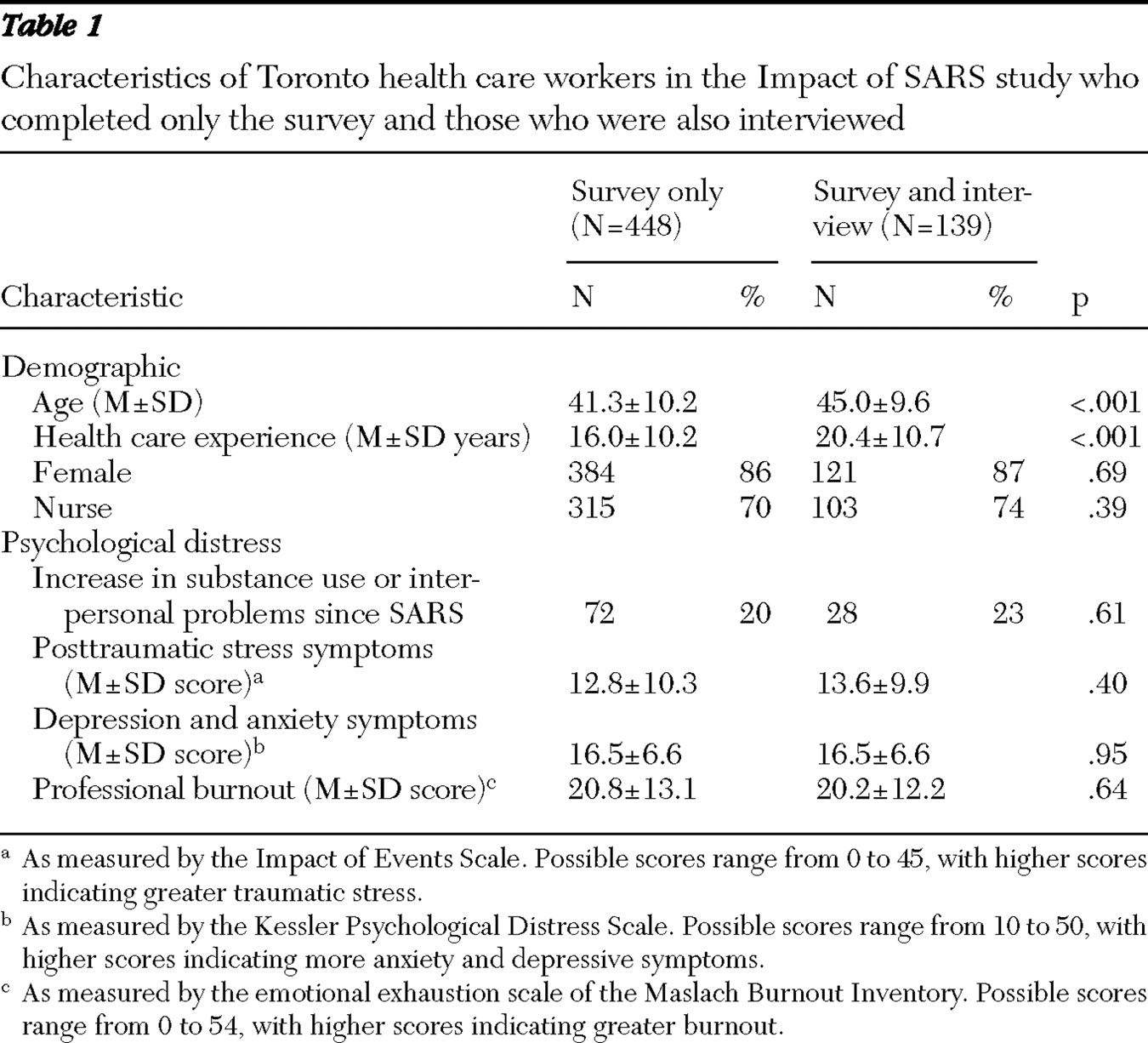

As shown in

Table 1, of 139 participants, 87% were female, and 73% of the sample were married or living in common-law relationships. The mean age was 45.0 years, and the mean number of years of health care experience was 20.4. Of the 139 participants, 112 (81%) were Western European; 11 (8%) were Asian, Southeast Asian, or Philippine; eight (6%) were African or West Indian; seven (5%) were Eastern European; and one (<1%) was from another group. A total of 103 participants (74%) were nurses, and 15 (11%) were clerical staff. The remaining 21 participants (15%) were employed in 15 other hospital job types. During the SARS outbreak, 88 participants (63%) had worked five or more shifts in the emergency department, intensive care unit, or a SARS isolation unit. A majority (105 participants, or 76%) reported contact with SARS patients.

As shown in

Table 1, compared with health care workers who completed the survey portion of the Impact of SARS Study but were not interviewed, participants who agreed to be interviewed were significantly older and more experienced in health care but did not differ by gender or job type or in any of several aspects of psychological distress.

The interval between the date when the last SARS patient was discharged or died and study participation ranged from 13 to 22 months (median 18). The CAPS interview, which was administered to 139 health care workers, identified four (3%) with a lifetime history of PTSD. Of these, two met criteria for current PTSD and one identified the SARS experience as the most severe traumatic event. Among the 133 participants who were administered the SCID interview, the lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV axis I diagnoses that were present before the SARS outbreak was as follows: major depression, 14 participants (11%); panic disorder, eight (6%); generalized anxiety disorder, four (3%); social phobia, eight (6%); agoraphobia, three (2%); specific phobias, five (4%); somatoform disorders, four (3%); and substance abuse or dependence, six (5%). A total of 40 health care workers (30%) met diagnostic criteria for at least one of these disorders during their lifetime before the SARS outbreak.

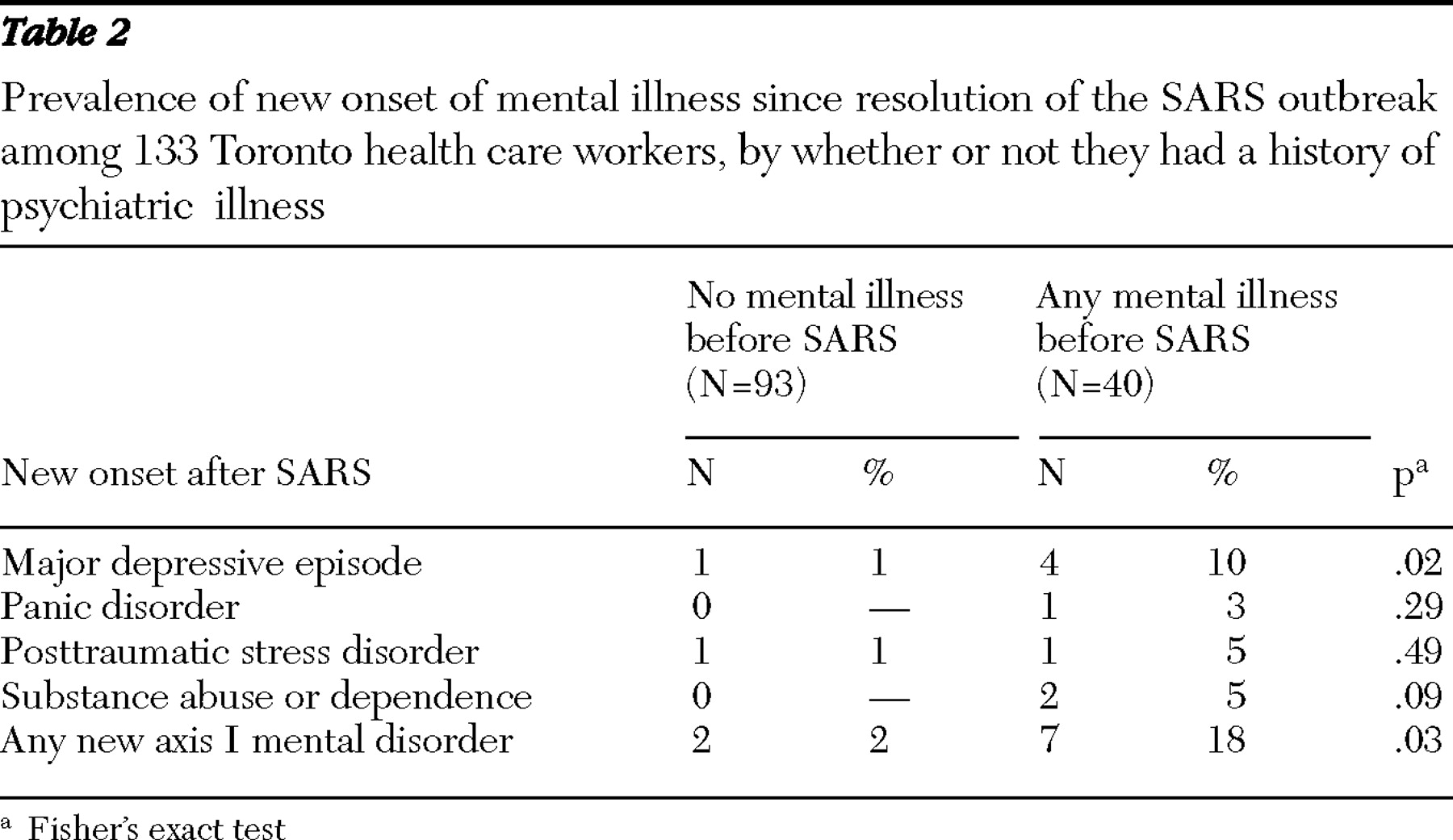

In the time since the SARS outbreak, 25 health care workers (19%) experienced panic attacks. Thirteen of these participants had a psychiatric history identified by the structured interviews. That is, 13 of the 40 workers (33%) with a psychiatric history experienced panic attacks after SARS, compared with 12 of the 93 workers (13%) with no identified psychiatric history (p=.01). As shown in

Table 2, new onset of major depression and new onset of any psychiatric disorder were also more common among health care workers with a history of psychiatric illness. Altogether, seven health care workers (5%) experienced a new episode of a psychiatric disorder in the one to two years after the resolution of the SARS outbreak.

We used logistic regression to determine whether the variables that were associated with psychological distress in a previous analysis (

6 ) were also associated with episodes of a psychiatric disorder. The results showed a significant association (R

2 =.13, p=.002) of the onset of any axis I diagnosis after SARS with a previous psychiatric history (

β =.22, p=.02) and an inverse (protective) association with years of health care experience (

β =-.21, p=.03) and with the perception of being adequately trained and supported by the hospital or clinic (

β =-.20, p=.03).

Discussion

This study found that one to two years after the resolution of the SARS outbreak in Canada, the incidence of new episodes of major depression among health care workers who were still working was 4% (five of 133 participants) and the incidence of new-onset PTSD was 2%. The incidence of any new onset of a psychiatric disorder was 5%. These incidence rates appear to be lower than those found in the general population. For example, the estimated annual incidence of major depression in Canada for women aged 25 to 44 has been reported to be 4.5%, and for women aged 45 to 64 it is 4.1% (

28 ). The incidence of depression also appears to be lower than the recently reported one-year rate of 9% for Canadian nurses (

29 ).

Given the previous report of significantly elevated long-term psychological distress among Toronto health care workers compared with colleagues at hospitals that did not treat SARS patients (

6 ), interpretation of this low incidence of new onset of episodes of a psychiatric disorder requires consideration of the distinction between distress and psychiatric disorder and attention to both the characteristics of the health care workers studied and the methodological limitations of the study.

The lifetime prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses among the health care workers studied is similar to that in the Canadian community (

30 ) with respect to major depression (health care workers, 10.5%; Canada, 12.2%), panic disorder (6.0% and 3.7%), social phobia (6.0% and 8.1%), and agoraphobia (2.3% and 1.5%). The lifetime prevalence of PTSD in an American community sample was 7.8% (10.4% among women) (

8 ), markedly higher than the prevalence in this study (2.9%). Rates of substance abuse or dependence are more difficult to compare with the Canadian community, where prevalence been described by using different criteria and time periods; however, lifetime rates among the health care workers appear to be lower than those found in the community (

31 ). Thus there was no indication of elevated susceptibility to psychiatric disorders among health care workers who participated in this study. The lifetime prevalence data are inconclusive with respect to the possibility of elevated resilience among the health care workers who participated in this study.

A critical question is whether the health care workers who participated in this study are representative of their colleagues. There are two points in the recruitment process that require scrutiny. First, were health care workers who participated in the Impact of SARS Study similar to those who chose not to participate? The results of a previously reported representativeness survey confirmed that health care workers who participated were similar to colleagues at the same hospitals who did not participate with respect to age, years of health care experience, job type, gender, and overall perception of the negative impact of SARS (

6 ). Second, were the health care workers who participated in structured interviews similar to those who completed only the survey? All of the information available from the survey questionnaires confirms that psychological distress was similar among health care workers who were interviewed and those who were not (

Table 1 ). The evidence supports this sample as being representative of health care workers at the participating hospitals.

It is important to note that this study did not include health care workers who stopped working, moved, or were not working because of long-term disability during the study period. As a result, mental health problems severe enough to result in persistent disability were not included. Thus, although the results of this study are consistent with the interpretation that the SARS outbreak did not increase risk for psychiatric disorders in health care workers, caution is required. Studies of excessive disability and sick-time after the SARS outbreak would be useful but are not currently available. The selection of working health care workers may explain why the overall rate of major depressive episodes since SARS is lower than that recently reported for Canadian nurses (

29 ). It is also important to note that confidence intervals on prevalence rates are large because of the sample size. For example, the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval of the rate of new episodes of major depression after SARS is 8.6%.

Why was there increased psychological distress (

6 ) but no concomitant increase in psychiatric disorders in health care workers after SARS? The critical difference between distress and psychiatric disorder is the impact of that distress on social and occupational function. We interpret our findings as a demonstration of the resilience of health care workers who continue to work in their field after their experience with SARS. Attributing this result to resilience is consistent with the finding that having more years of experience in health care work was associated with a lower incidence of psychiatric disorders. These findings are also consistent with previous studies of mass trauma, which have found a lower of incidence of PTSD after natural disasters than after events of malicious human intent and a lower incidence of PTSD in communities with high levels of social support (

32 ).

Conclusions

The study confirmed the prediction that new episodes of psychiatric disorders would be more prevalent among health care workers with a history of psychiatric illness. In a health care setting, especially in the context of preparing for an influenza pandemic and other emergent diseases, this finding highlights the relevance of health care workers' being attentive to their own personal risk in order to respond quickly to emergent symptoms of anxiety or depression. Furthermore, this study confirms the hypothesis that health care workers who feel well supported and trained by their employer experience better mental health over the long term. Among the predictors of risk in this study, training and support are the factors that are most amenable to preventive intervention within an organization. This finding suggests that even among health care workers who are at elevated risk of a psychiatric disorder by virtue of unmodifiable factors (such as having less experience or having a history of a psychiatric disorder), efforts by a hospital to offer effective practical and emotional support and to provide training in novel tasks and personal protection significantly enhance resilience.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by an operating grant SAR-67807 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

The authors report no competing interests.