Peer-based treatments are gaining popularity in traditional service venues for persons with severe mental illness (

1 ). Several authorities have suggested that the success of these services may be largely attributable to peer providers' ability to readily forge favorable relationships with clients (

2,

3 ). Recent evidence supports these suggestions. In a previous study comparing clients of peer providers and of traditional providers, the former reported that they perceived higher levels of validating qualities such as empathy; moreover, clients who perceived that their providers had such qualities were more likely to report motivation for and engagement in community-based treatments (

4 ). Such findings are consistent with those of traditional psychotherapy research, in which a therapist's warmth, understanding, and acceptance are shown to foster strong working alliances and positive therapeutic outcomes (

5 ).

Interpersonal transactions between health care providers and clients are complex, however, typically reaching beyond the provision of validation. Nevertheless, it seems a strongly held belief that the positive impacts of peer-based treatments are attributable to clients' experiences of generic validation through such qualities as provider warmth and understanding. However, this conceptualization is incomplete and conflicts with documented and successful practices in other peer-based services, such as therapeutic communities, where potentially invalidating confrontation may be enacted within the spirit of therapeutic benefit (

6,

7 ). For instance, a peer provider may choose to express dissatisfaction with a client based on the client's recent drug use or may refuse to understand or may cut short a client's self-denigrating statements. Although such practices may not typify peer-based treatment, the prevalence and impact of clients' experiences of invalidation from providers are underresearched and, to the best of our knowledge, have yet to be examined in the context of peer-based services within traditional service venues for persons with severe mental illness.

This article reports results of a randomized controlled trial that compared the occurrence and outcomes of clients' experiences of invalidation in peer-based and traditional intensive case management services for persons with severe mental illness, the majority of whom had co-occurring drug use problems. We hypothesized that compared with clients in traditional intensive case management, those who received services from peer providers would perceive that provider communications were more validating than invalidating as reflected by levels of positive regard, empathy, and unconditional acceptance. We also hypothesized that perceived invalidation from peer providers but not from traditional providers would be significantly associated with favorable client outcomes, including enhanced quality of life and fewer perceived obstacles to recovery.

Results

Mixed ANOVA

Results of mixed ANOVA revealed a robust main effect for relationship quality (F=96.54, df=1 and 102, p<.05; η 2 =.49); clients in both peer-based and traditional treatment perceived that interactions with and communications from their providers were significantly more validating than invalidating. More pertinent to the hypotheses, results also showed a significant valence-by-condition interaction (F=9.54, df=1 and 102, p<.05; η 2 =.09), in which participants in peer-based treatment perceived communications as significantly more validating than invalidating compared with participants in the control condition. There were no main effects for condition.

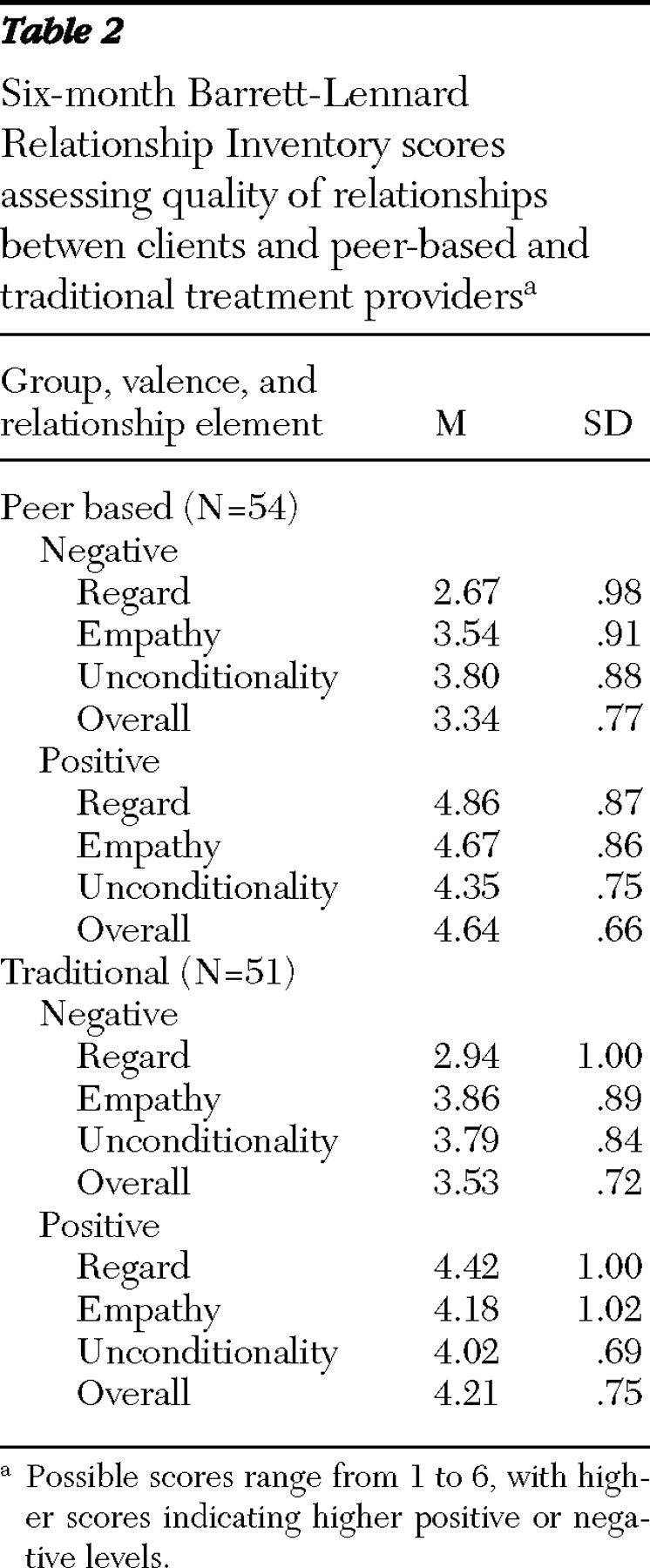

Table 2 presents six-month means and standard deviations for BLRI scores, which indicate relationship quality, by condition, valence (positive and negative), and relationship element (regard, empathy, and unconditionality). At the six-month follow-up, 23% of the overall sample did not complete the BLRI questionnaire, either because of study drop-out or incomplete interviews, which is not uncommon in studies that include persons with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use problems (

18 ). Chi square analyses confirmed that the difference in attrition between groups was not significant.

Regression analyses

Results revealed significant moderator effects of invalidation-by-study condition across ASI and QOLI-B subscales at the six-month follow-up but not at the 12-month follow-up. Specifically, negative regard and a composite negative overall index (mean score for negative empathy, negative regard, and negative unconditionality) were found to have significant predictive effects on outcomes.

Table 3 presents statistical data for all significant moderating analyses, and

Table 4 shows results of follow-up simple-effects tests.

As shown in

Table 3, after controlling for ASI medical composite baseline scores, regression analyses revealed that among those in peer-based treatment, an increase in the negative overall index at six-month follow-up predicted a decrease in the ASI medical composite score at six-month follow-up significantly more so than for those in traditional treatment. Simple-effects findings, which are shown in

Table 4, specified that when the analyses controlled for baseline levels, the negative overall index at six months significantly predicted a decrease in the ASI medical composite score at six months (indicating improvement) among participants in peer-based treatment but not in the control condition.

When the analyses controlled for baseline scores on the ASI psychiatric composite, an increase in the negative overall index at the six-month follow-up predicted a decrease in ASI psychiatric composite score at six months significantly more so than for those in traditional treatment. Simple-effects analyses showed that the negative overall index significantly predicted a decrease in the ASI psychiatric composite score for those in peer-based treatment but not for those in traditional treatment. No other ASI composite subscale (for example, drug use) showed a significant moderation pattern.

After the analyses controlled for baseline scores on the QOLI-B health subscale, an increase in the negative overall index at the six-month follow-up among those in peer-based treatment predicted an increase in the QOLI-B health subscale at six months significantly more so than for those in traditional treatment. Simple-effects analyses showed that the negative overall index significantly predicted increases in the QOLI-B health score for those in peer-based treatment but not for those in traditional treatment.

When the analyses controlled for baseline scores on the QOLI-B family subscale at six-month follow-up, an increase in perceived negative regard among those in peer-based treatment at six months predicted an increase in the QOLI-B family score significantly more so than for those in traditional treatment. Treatment condition also moderated the relation between baseline scores on the QOLI-B family subscale and the same subscale scores at six months. Simple-effects analyses showed that negative regard significantly predicted increases in QOLI-B family scores for those in peer-based treatment but not for those in traditional treatment. No other QOLI subscale scores showed a significant moderation pattern.

No other significant results were found at 12 months when we used the same analyses.

Discussion

Results of this study support the hypothesis that participants who received peer-based intensive case management services would perceive that their providers communicated in ways that were more validating than invalidating compared with participants who received services from traditional providers. In addition, results support our hypothesis that provider type (peer or traditional) would moderate the association between the perception of invalidation from the provider and favorable client outcomes.

These findings are consistent with the notion that peer providers may serve a validating role for clients with severe mental illness. However, they also suggest that early in the course of treatment, peer providers' invalidating communications predict greater client benefits than the invalidating communications of traditional providers in terms of fewer psychiatric and physical health problems, better perceived medical health, and better relationships with family members. It should be noted, by contrast, that traditional providers' invalidating communications did not appear to lead to unfavorable client outcomes across these analyses. Moreover, the differential effects we found for provider type held true only early in the treatment process, at six months but not at 12 months. Thus it may be that the relative positive effects of invalidation in peer-based services operate chiefly within the early, engagement phase of treatment.

These findings speak to the potential benefits of employing peer providers in traditional service venues serving persons with severe mental illnesses. The role of these providers, although typically conceived within a constellation of validating qualities such as ally and advocate (

19 ), appears to possess favorable transformative power through invalidating channels as well. Although the precise nature of these channels is unclear, it may share a conceptual foundation with what White (

19 ) described as the "truth-teller" role of peer-based treatment relationships, through which a peer provider may offer measured invalidating communication to a client about her or his potentially deleterious behaviors, beliefs, and so on. These communications may not differ substantially from those received from traditional providers, but within the context of the peer provider's disclosed experiential background and greater client-perceived validation, clients may more readily appreciate invalidating communications and use them as an impetus for improving their lives. It is up to future research to specify how and when such invalidating "truths" are offered to clients in peer-based and traditional treatment and, furthermore, to empirically link those instances to clients' experiences of invalidation by providers and client outcomes.

This research had several limitations. First, although the study examined differential impacts of provider type on client process and outcome, the work did not specifically differentiate treatment practices among traditional and peer providers as has been done by others in this area (

20,

21 ). As a result, the study was not able to distinguish specific validation practice, and thus it remains unclear to what extent validation was differentially offered by peer and traditional providers to address personal, behavioral, or other considerations. Furthermore, it is possible that the programmatic context of this investigation, in which peer and traditional providers worked together on the same teams, may have compromised internal validity through contamination of distinct traditional and peer-based treatment practices. Moreover, the intensity of client services in the peer-provider condition, in which peer and traditional providers often work side by side, may have accounted for observed differences between conditions. Nevertheless, in traditional service agencies that employ peer providers, it is not uncommon to have them work with traditional staff (

22 ); although these practices may pose challenges to investigative internal validity, the service context of this investigation does represent the actual circumstances under which such treatments are often delivered and thus serves external validity.

Second, it is possible that the results obtained in this investigation could be attributed to peer providers' smaller caseloads, insofar as traditional case managers may have had neither adequate time nor energy to work with clients with the same level of demonstrated investment as peers. It is important for future research to better control for client caseload and also to determine suitable caseload levels for optimal service provision for both traditional and peer-based intensive case management services.

Third, data in this study were based primarily on client self-report. Provider judgments on measures such as the BLRI have been shown by investigators to predict client outcomes (

23 ); clinician ratings have also been shown to be linked to aspects of recovery such as hope (

24 ). Although client self-ratings appear to be good predictors of outcome in psychotherapy investigations, future research should determine the best predictors of outcome in peer-based treatment. In addition, it is possible that changes made to the BLRI for the purposes of this study compromised its validity.

Fourth, study participants represented a convenience sample whose reports may have diverged from those who declined participation; although the refusal rate was not tracked systematically, staff estimations made after the study was completed suggest that it was below 5%. In addition, the study sample was small, and missing data with respect to the BLRI at six months was 23%, which may limit statistical validity and study generalizability. The statistical tests indicated robust differences, and therefore statistical validity was not of primary concern. Future research on this topic, however, would do well to include larger samples to maximize generalizability. This is particularly important in studies of persons with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders, who are known to show high levels of attrition in community-based services research. Nevertheless, chi square analyses showed that attrition did not differ between peer-based and traditional treatments.