According to large national and international surveys, psychiatric disorders occur frequently in the general population (

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9 ). In response to the discomfort caused by these disorders, relatively few people use specialty mental health care, defined as care rendered by individuals trained to assess, refer, and treat persons with mental or emotional problems. In a review, Kohn and colleagues (

10 ) calculated that more than 50% of mental health needs remain unmet. However, there are several other types of responses to psychological distress (

11 ). As posited by the self-medication hypothesis and the alleviation of dysphoria model (

12,

13,

14 ), psychoactive substance use is one of these responses and has been described in different populations (

15,

16,

17 ). Bolton and colleagues (

18 ) described substance use in response to lifetime anxiety disorders using the data of the 1990–1992 National Comorbidity Survey and found that frequencies of this type of substance use ranged from 7.9% (social phobia, speaking subtype) to 35.6% (generalized anxiety). However, frequencies were not estimated separately by gender, even though gender is known to be linked to substance use and to mental disorders (

9,

19 ). Moreover, mental health care use has not been studied jointly with substance use as responses to psychiatric disorders. Patients with psychiatric disorders who use health care are likely to be relieved from their psychological symptoms, so that their need to use psychoactive substances should be lower compared with persons not using health care. Previous studies showed that mental health service use was associated with lower rates of substance use disorders among persons with two or more psychiatric disorders (

20,

21 ).

The objectives of the study presented here were to estimate by gender the frequencies of use of psychoactive substances and of health care in response to anxiety or depressive disorders and to determine factors associated with these behaviors. Data for this study were gathered with a large population-based survey.

Methods

Study design and setting

We used data from a cross-sectional survey designed to assess mental health indicators in France. Four regions of France volunteered to participate in this survey: Ile de France, Haute-Normandie, Lorraine, and Rhone Alpes. In each region, participants were selected with a two-stage procedure. First, households were randomly selected, and then one adult per household was randomly selected according to a method proposed by Kish (

22 ). Sampling was based on a file of listed numbers obtained for each region from the telephone directory. A new list was obtained by replacement of the last digit by a randomly chosen one. Thus it contained listed and unlisted numbers. Exclusion criteria for households were not living in one of the four regions, not answering after 15 calls, not being a French speaker, and declining to participate in the survey.

Exclusion criteria for participants were being younger than 18 years, not answering after 15 calls, being a non-French speaker, being unable to answer the phone or complete the interview (could not hear the questions, did not answer the questions or answered inconsistently, was under the influence of alcohol or other psychoactive substances, or had a physical illness that prevented him or her from talking for a long time), and declining to participate in the survey.

Sample

For the study presented here, only participants with a probable 12-month anxiety or depressive disorder were selected. Those with a 12-month substance use disorder were excluded.

The study protocol was approved by the French regulation authority for questionnaire-based noninvasive medical research (Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés). Participants were given a complete description of the study and were asked to provide informed consent.

Data collection

Data were collected by phone from April to June 2005 by trained interviewers who used computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI). CATI employs interactive computing systems to assist interviewers and their supervisors in performing the basic collection tasks of telephone surveys.

Sociodemographic variables. Sociodemographic variables were gender, age, marital status, education level, housing ownership, and country of birth.

Anxiety and depressive disorders. DSM-IV (

23 ) axis I disorders were assessed with the short form of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI-SF) (

24 ). This instrument made it possible to assess the probability of the presence of the following disorders: major depressive episode, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), panic attack, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, specific phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and alcohol or drug use disorders (abuse and dependence). This version was adapted from the French version of the CIDI used in the European Survey of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) (

25 ). In this study, only probabilities of having a 12-month disorder were calculated.

Disability. Disability was assessed by the Sheehan Disability Scale for each disorder separately (

26 ). This scale allows the evaluation of disability by using four questions dealing with work, home life, social life, and family life. The answer to each question is coded from 0, no disability, to 10, severe disability; a score of 7 or above is considered to represent a significant impairment. Because all four questions did not necessarily apply to every participant, we computed an average score over the questions that were applicable. Participants were then considered as disabled by their condition if their average score was 7 or above.

Responses to anxiety and depressive disorders. In the course of the interview, each disorder corresponded to a section of the questionnaire. After questions about the disorder's symptoms, questions were asked concerning the participant's responses to these specific symptoms: consulting a medical doctor (general practitioner, psychiatrist, or other medical specialist specified), consulting a nonmedical mental health provider (psychologist or psychotherapist), consulting another professional (social worker or nurse), or using psychoactive substances (alcohol or illicit drugs). These questions were asked separately for each anxiety or depressive disorder. Therefore, it was possible to determine the presence or absence of these responses for each anxiety or depressive disorder.

Consultation with a social worker, a nurse, or another professional was not categorized as health care use in this study, because in France they are not mental health professionals.

Perceived social support. Social support was documented with four questions (

27 ): Do you have a close friend or family member with whom you can easily talk about your problems? Do you know someone you can count on in case of crisis? Do you know someone you can count on when you have important decisions to make? Do you have someone who makes you feel loved? Participants who answered no to all questions were considered to not have any social support.

Statistical analysis

In order to adjust for differential representation, observations were weighted by the reciprocal of the selection probability (

28 ).

First, frequencies of responses to psychological distress were calculated by gender for each disorder. Four types of responses were distinguished: using psychoactive substances (alcohol or illicit drugs), consulting a psychiatrist, consulting another medical doctor, and consulting another mental health professional (psychologist or psychotherapist).

Second, because these responses to disorders are not mutually exclusive, we combined health care and psychoactive substance use as follows: health care use only (without psychoactive substance use), psychoactive substance use only (without health care use), both health care and psychoactive substance use, and use of neither of them.

Health care was defined as consultation with a psychiatrist, another medical doctor, or another mental health specialist. We combined provider types into a single health care category because we were interested in the act of seeking help with a mental health professional, regardless of the specialty. The main question this article examined was the use of psychoactive substances in response to psychiatric disorders, and we wanted to compare this type of substance use to an "appropriate" response. Frequencies of use were calculated without considering each disorder separately. If a participant had several disorders, we determined that he or she had used health care if he or she had done so for at least one disorder and that he or she had used substances if he or she had done so for at least one disorder. Thus a participant who had used health care for a given disorder and substances for another one was classified in the group of those using both health care and substances.

Finally, we studied factors associated with the four categories of substance and health care use with a multinomial logistic regression, which allows the analysis of a qualitative dependent variable with several levels (

29 ). Each level of the variable is compared with a reference level, for which the odds ratios for each covariate are supposed to be equal to one. In our study, this reference level was "health care use only." Covariates were age, gender, size of the town, region, country of birth, matrimonial status, education level, housing ownership, social support, type of disorder (depressive, anxious, or both), and disability. A participant with several disorders was classified as having severe disability if he or she scored as having severe disability for at least one of the disorders. Covariates were selected according to a stepwise descending procedure, and an association was considered as being significant when the p value was less than .05. Nonsignificant variables were not kept in the final model unless they appeared as confounding factors. Finally, interactions were tested between selected covariates. These analyses were performed using SAS proc surveymeans and proc surveylogistic.

Results

Of the 59,836 phone numbers randomly generated, 38,612 belonged to households. Among these households, 28,243 were available for the second step of the selection (proportion of contacted households 73.1%).

After selection of the participant in the household, 2,795 could not be contacted after 15 calls, 2,114 did not wish to participate, 610 were absent for a long period, 1,357 persons did not meet inclusion criteria, 702 were considered to be unable to complete the interview, and 588 did not complete the entire interview. Thus 20,077 participants completed the interview (response rate among contacted households 71.1%). Among them, 4,301 suffered from a probable 12-month anxiety or depressive disorder. Of them, 230 had a 12-month substance use disorder and were excluded. The final sample size was thus 4,071. [A flowchart showing the selection procedure is available as an online supplement at

ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

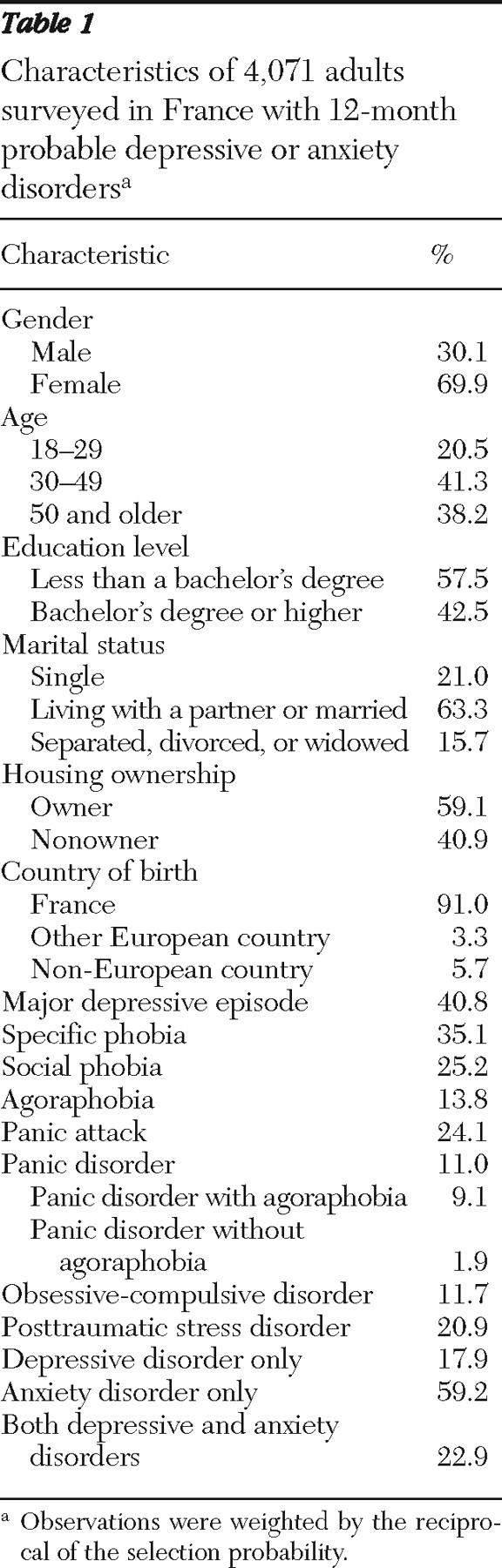

The sample is described in

Table 1 . Major depressive episode was the most frequent psychiatric disorder found, with a 12-month prevalence estimate of 40.8% (

Table 1 ). Among anxiety disorders, the most frequent was specific phobia (35.1%). More than half of those having a depressive disorder also had a comorbid anxiety disorder.

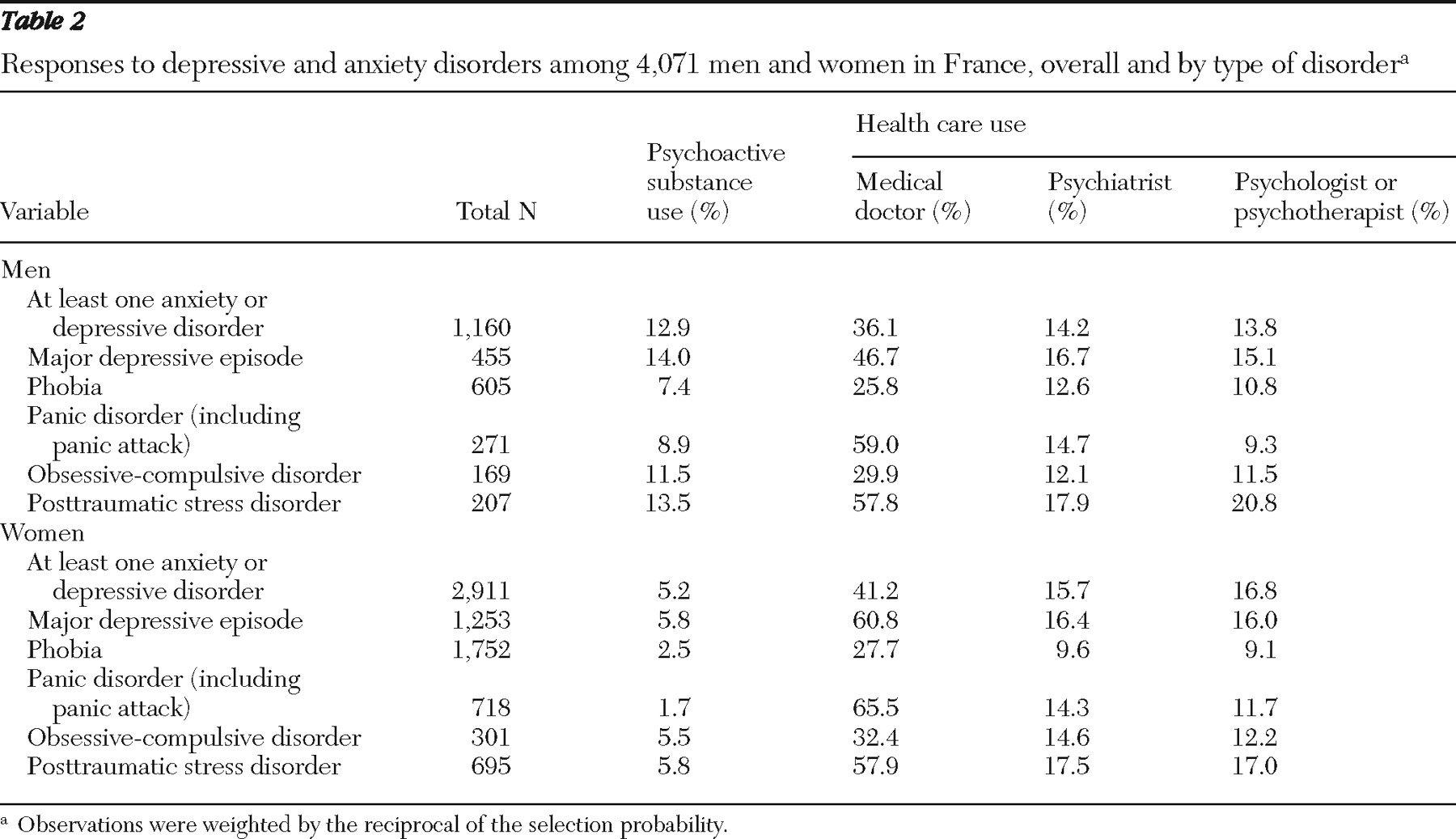

Among men, frequency of substance use in response to a depressive or anxiety disorder was 12.9% (

Table 2 ). Substance use was more frequent for a major depressive episode, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or PTSD (all more than 10.0%). Substance use was less frequent than health care use, regardless of the type of care provider.

Frequency of substance use was lower among women (5.2%) than among men (

Table 2 ). As observed among men, substance use was more frequent for a major depressive episode, an obsessive-compulsive disorder, or a posttraumatic stress disorder and was less frequent than health care use, regardless of the type of care provider.

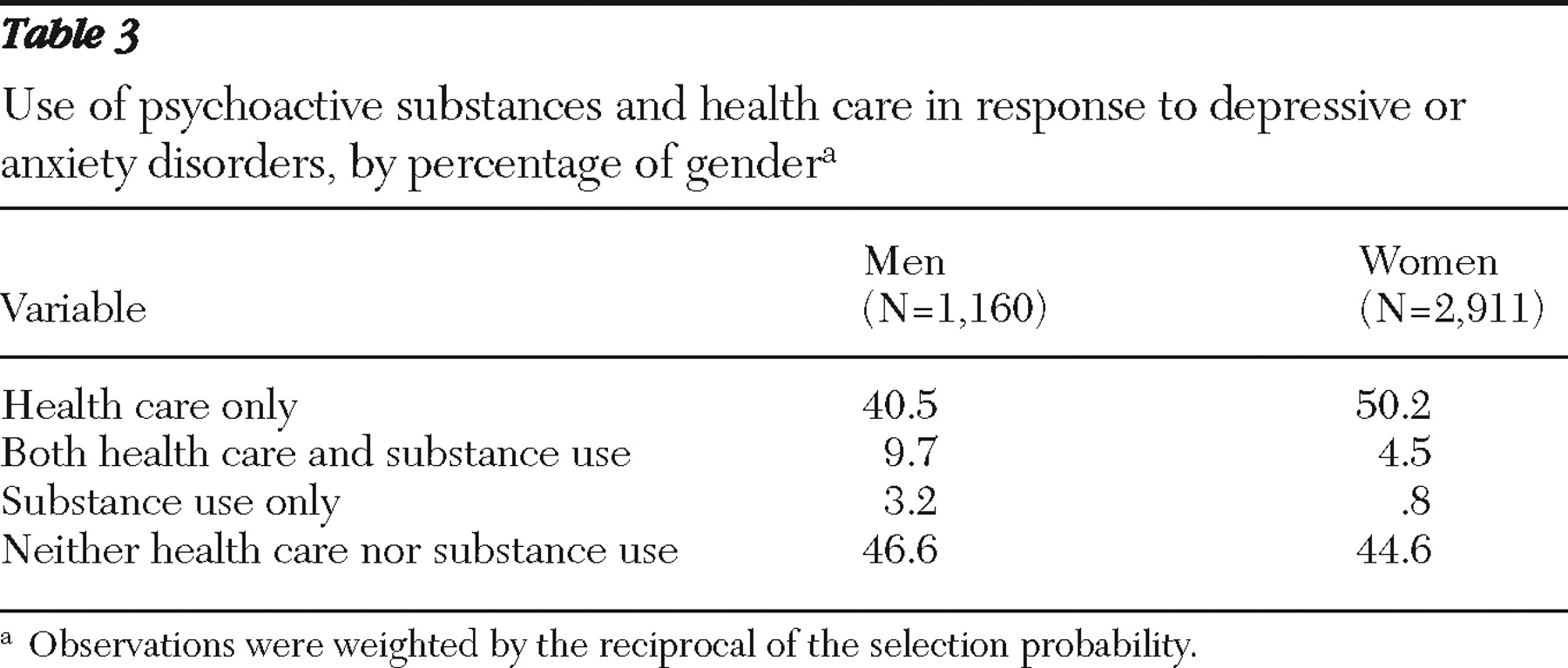

Substance use, health care use, and use of both in response to anxiety or depressive disorders are presented in

Table 3 . Among women, the greatest proportion used health care only, whereas among men, the greater proportion used neither substances nor health care. Men and women used both health care and psychoactive substances more frequently than they used psychoactive substances alone.

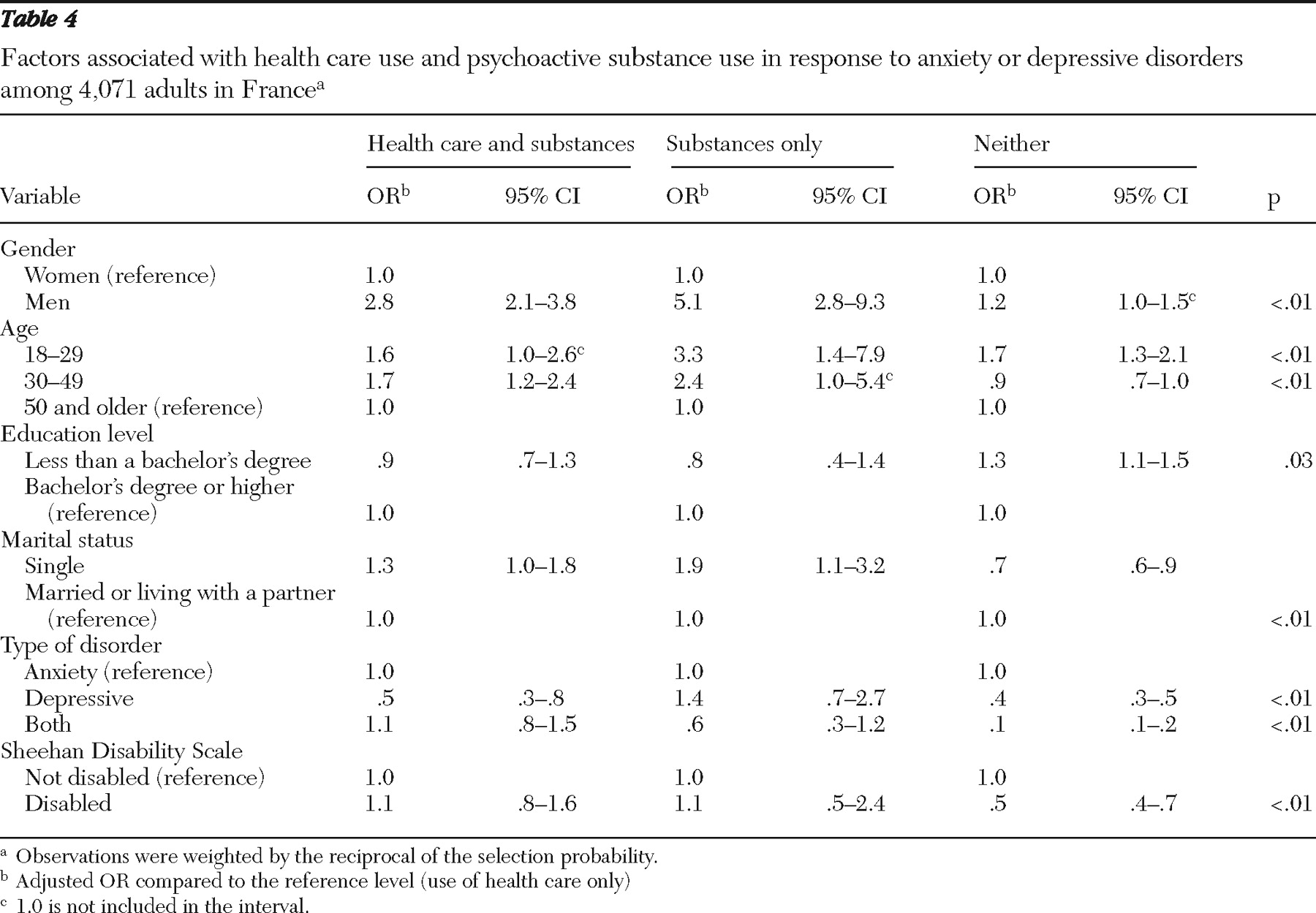

Adjusted odd ratios (ORs) of factors associated with responses to anxiety or depressive disorders are presented in

Table 4 . Compared with those who used health care only, those who used both health care and substances were more frequently men (OR=2.8), more often aged between 18 and 29 (OR=1.6) or between 30 and 49 (OR=1.7), and less likely to have a depressive disorder only (OR=.5).

Compared with those who used health care only, those who used substances only were more likely to be men (OR=5.1), aged between 18 and 29 (OR=3.3) or between 30 and 49 (OR=2.4), and single (OR=1.9).

Finally, compared with those who used health care only, those who used neither substances nor health care were more likely to be men (OR=1.2), to be aged between 18 and 29 (OR=1.7), and to not have a bachelor's degree (OR=1.3), and they were less likely to be single (OR=.7). They were less likely to have a depressive episode (with or without an anxiety disorder) and less likely to have a severe disability (OR=.5 for both).

Social support, size of town of residence, region, country of birth, and housing ownership were not significantly associated with health care use or substance use and were not confounding factors.