Case manager perspectives on disengagement

Disengagement as part of the trade. The following themes emerged from the case manager interviews. Most case managers expressed having anticipated that their clients would leave the program prematurely, citing previous experience. As one case manager noted, "These kinds of places are inherently revolving doors." Another explained, "We're not taking bets, but sometimes me and the case managers, we'll get together and the clients will come in, and we can look and say, you know what, the client ain't going to make it. You could just tell sometimes by the way they come in, their behavior. And a lot of times we hope to be wrong." Some of the case managers spoke in schematic terms, such as "He's the kind of guy [who would disengage] and we knew it from the beginning" or "That type of person can't stay put too long." There was often a sense of inevitability and resignation to the possibility of disengagement, with one case manager concluding, "It's part of the trade."

In the baseline interviews, anticipating disengagement was not reported, but case managers clearly were concerned about the consumer's prospects in the program. One explained, "We don't have the highest expectations other than that they continue to show up. And [that they] know that we care about them." Referring to the program and its rules requiring sobriety, another case manager said, "It's hard to say right now.… If he doesn't stop smoking marijuana, I think he's gonna have a problem with that." In this case, the consumer was discharged to a more structured drug treatment setting. Some case managers expressed a belief that they could influence consumers to change their behaviors, with one explaining, "I told her too, you know, 'You really have to focus on yourself. You can't help your children if you're constantly getting high. Or you don't have a place to stay.' So I think that kind of woke her up too." Often consumers did disengage as a result of substance use, but one consumer, who was perceived by his case manager to be using substances, had actually negotiated a placement in independent living with another agency without the case manager's assistance or knowledge.

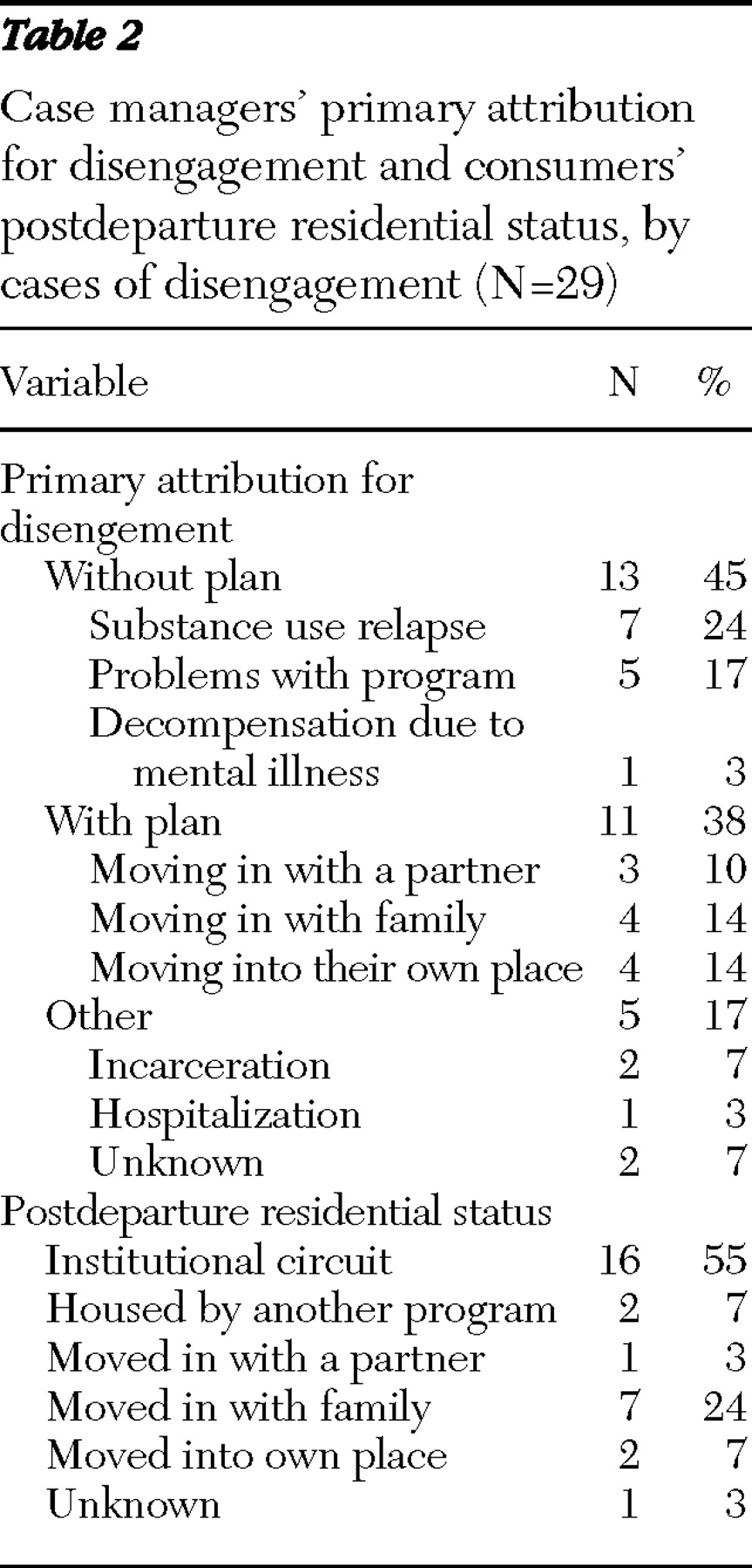

Disengagement as poor decision making. Virtually all case managers characterized disengagement as a mistake emanating from poor decision making on the part of the consumer. This held true even when consumers articulated a plan to leave and subsequently moved in with family members or on their own. Although one case manager conceded "at least he had a plan," most believed that consumers were not ready to make it on their own, attributing this to struggles with substance use. For instance, one case manager said, "He wants to use … and until he is committed to living his life sober, we can't help." This was often described in schematic terms, such as a consumer's being "nowhere near recovery yet. I think she's a chronic relapser." Another expressed frustration by saying, "He doesn't understand that there is a pattern, and we try to point it out."

Sometimes case managers attributed disengagement to the consumer's personality and difficult behaviors. One said, "I knew he would be challenging. He was very friendly, but at the same time he had a very strong sense of self-entitlement.… It just made it a very difficult combination to actually move forward with." Some viewed disengagement as an act of "self-sabotage," a phrase used to describe self-destructive behavior often precipitated by an impending referral to a less restrictive program. As one case manager stated, "He felt that he didn't have to listen to what staff had to say at that point, so we knew that when he was going through all of that, this is his signs that he's going to be sabotaging soon. So we saw those as signs of sabotaging, and that's what he did basically." This consumer did end up living on the streets.

Vocalizing disagreement with a consumer's decision was not uncommon. As one case manager recalled, "I didn't think it was a good decision at all. And I told him that." The consumer in this case returned to living with his mother after having complained that he was sexually molested at his program. Another case manager talked about a consumer who left to move in with his girlfriend, stating, "I think it's really unfortunate that he left, especially knowing who he decided to live with." Another said, "I'll tell them that they'll be back here in two weeks looking for a bed because their friend kicked them out." These opinions could have been a type of persuasion or simply an honest assessment, but case managers clearly put responsibility on the client.

The perception that disengagement was a mistake was often accompanied with a sense of disappointment, especially if the consumer was considered to show potential to do well. Consumers who were labeled "insightful," "very nice," or "the ideal consumer" were the ones in which case managers were more likely to say, "I'm disappointed because here's someone, in my assessment, [who] could have done so well" but instead was deemed to be "a big disappointment." Interestingly, only one case manager mentioned the program as contributing to disengagement by saying, "I can't blame them for leaving if they're not getting housing quick enough."

Coping with the revolving-door syndrome. Even when faced with a "disappointing" consumer, when asked whether they would be willing to work with the consumer again, most case managers answered affirmatively. One case manager said, "I would love for her to come back. She is an incredible person." Another said, "He's a little star," and added, "Hopefully, he'll reach out." In some cases, case managers said they would enforce a stricter regimen in order to better address substance abuse. In the few instances in which case managers were not willing to work with a consumer again, the decision was rooted in a belief that the consumer left them no alternative, which they expressed as, "[He] forced us to discharge him," "I think that he really sealed his fate," and "Basically, people are just tired of working with him."