Strengths and limitations

This study provided clinically detailed data on the experiences of a large, ten-state sample of psychiatric patients receiving Medicaid benefits. The primary limitation is this study's exclusive reliance on physician-reported, cross-sectional, observational data, which have potential response and recall biases. However, it is important to note that for many of the primary medication access problems of interest (such as clinicians' inability to prescribe a clinically indicated and preferred medication because of drug coverage or management issues), physicians would likely be the best source for this type of information. The physicians were compensated to help increase the response rates; however, physicians whose patients were experiencing medication access problems may have been more likely to respond to our survey or to deviate from the systematic patient sampling protocol.

The physicians may have lacked accurate information on their states' utilization management methods and policies or misattributed medication access problems to these policies, which are complex and can vary across and within medication classes. Because respondents were asked about plan features in general (that is, not specific to particular medication types or classes), the responses are best interpreted as general perceptions by clinicians of policies affecting their patients. Clinicians may be more inclined to report prescription drug policies when they encounter them or a medication access problem.

Although some data on state Medicaid prescription drug management policies are publicly available, the sources of information we identified were limited and not readily comparable across the states or specific to psychopharmacologic medications (

5,

15,

16 ). State prescription drug policies also vary between managed and fee-for-service plans within states; this variance was not assessed in this study. Pharmacies may also vary in implementation of prescription drug copayment or other policies. With a particular policy, such as prior authorization, utilization management practices may vary widely in application among patients. The ability to capture these complexities through provider or key informant reports and other sources is limited given the complexity of these arrangements and variations in policy implementation.

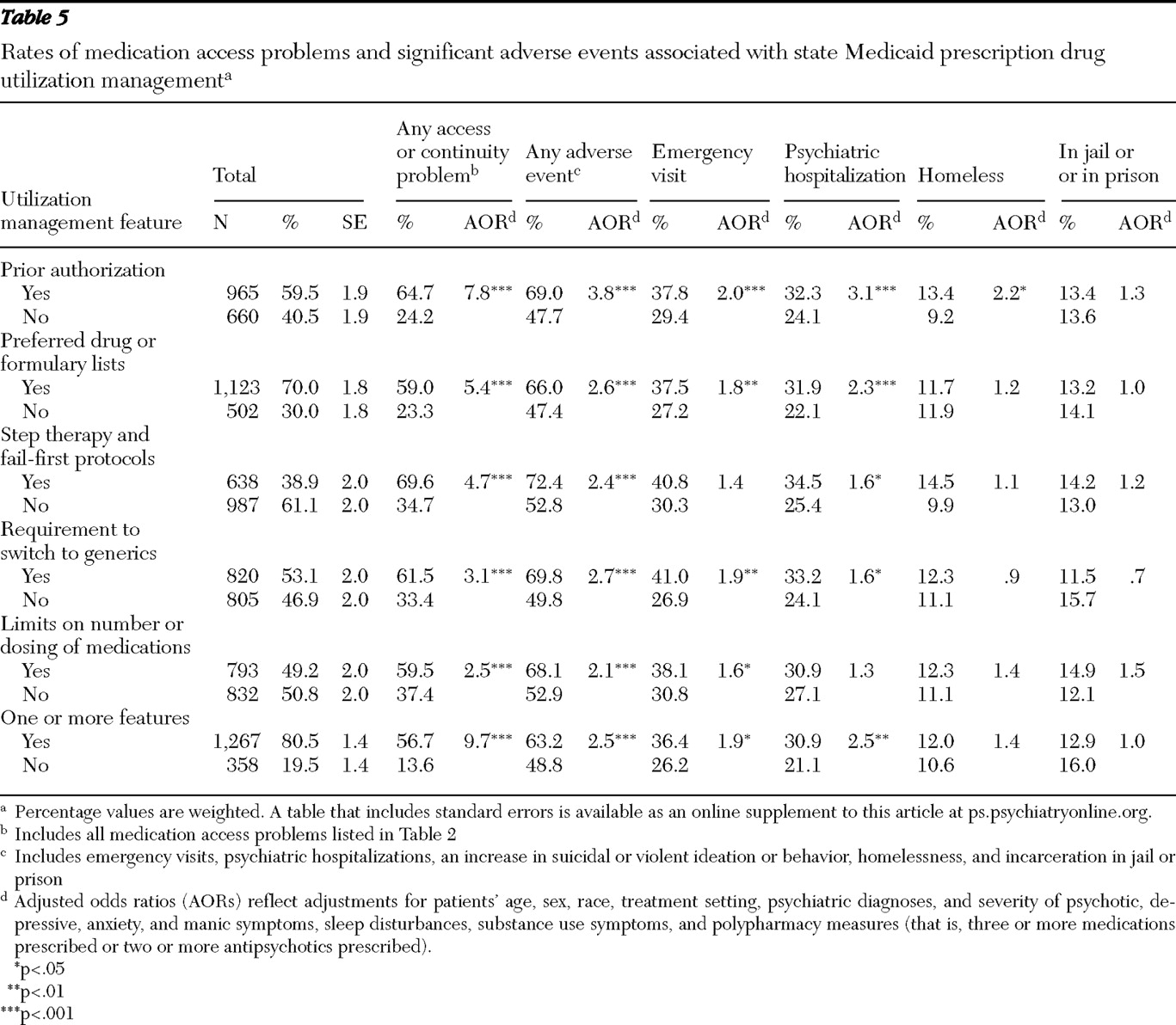

This observational study did not capture data on the timing of medication access problems and adverse events and allowed examination of only the associations between Medicaid policies, medication access problems, and adverse events (as reported by the physicians), thus limiting the ability to make causal inferences. Patients with more severe illness, who may require more complex medication regimens, may be more likely to experience medication access problems, to be subject to prescription drug utilization management policies, and to experience adverse events. The logistic regression analyses did, however, adjust for available patient-related covariates. In addition, the logistic regression analyses of the association between adverse events and utilization management features adjusted for two polypharmacy measures because patients with a polypharmacy regimen may be more likely to face adverse events and to have utilization management apply to their medications. Finally, although we presented p values as large as p<.05 to convey general patterns of associations, if a Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for the multiple tests (66 in total) in

Tables 3 and

5, which provide results from the primary study analyses, only those findings with a p value <.00078 would be considered statistically significant.

Key findings and policy implications

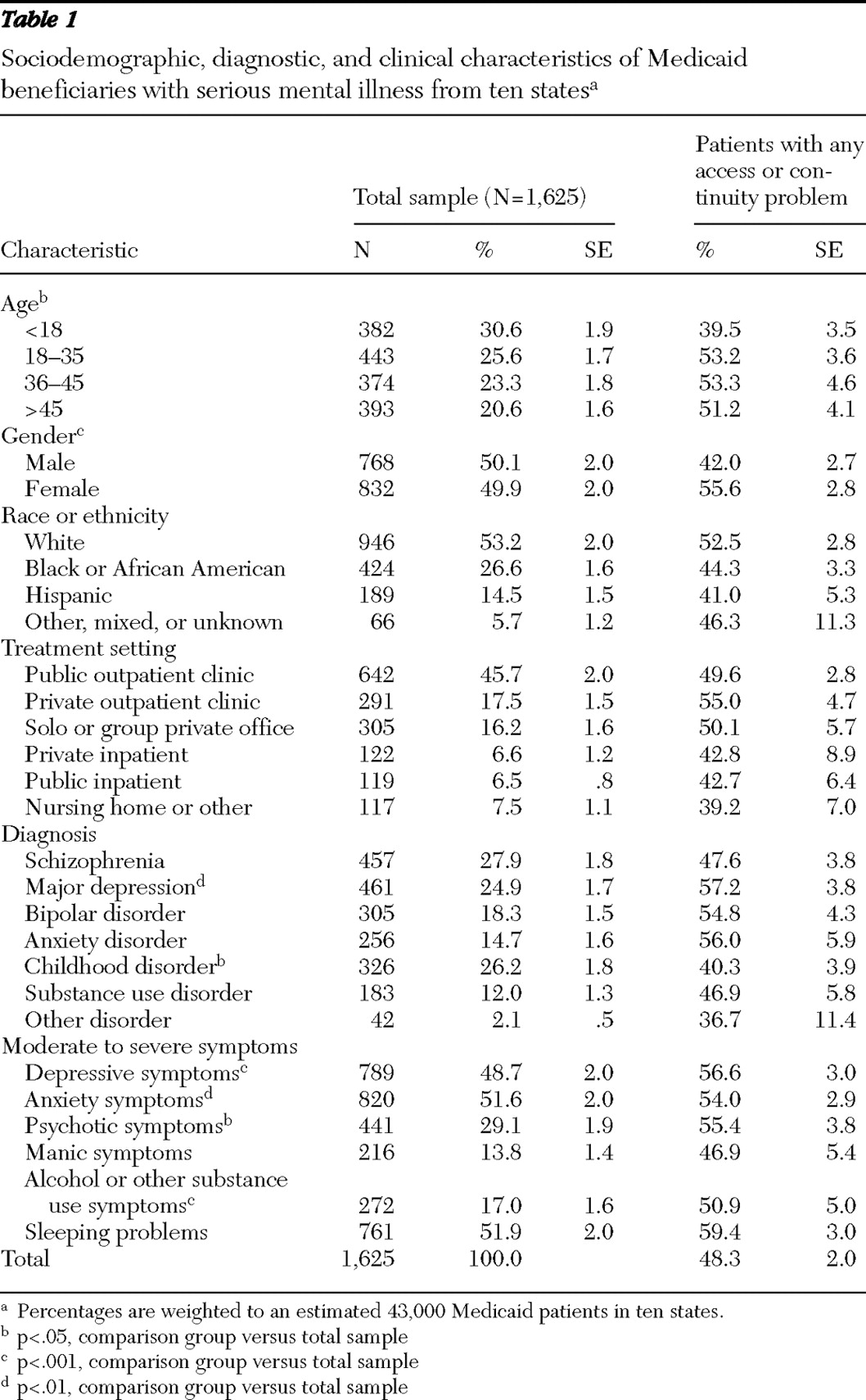

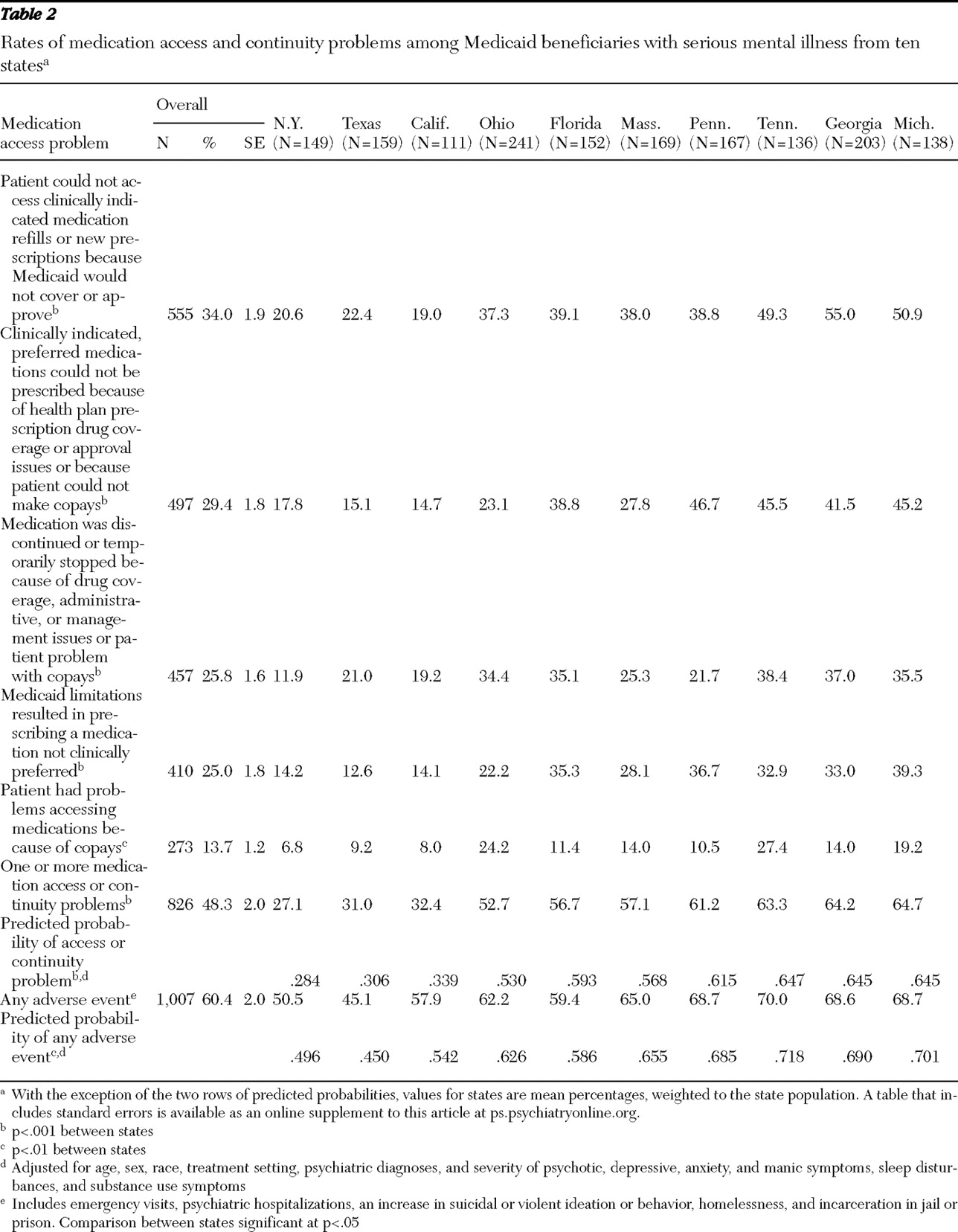

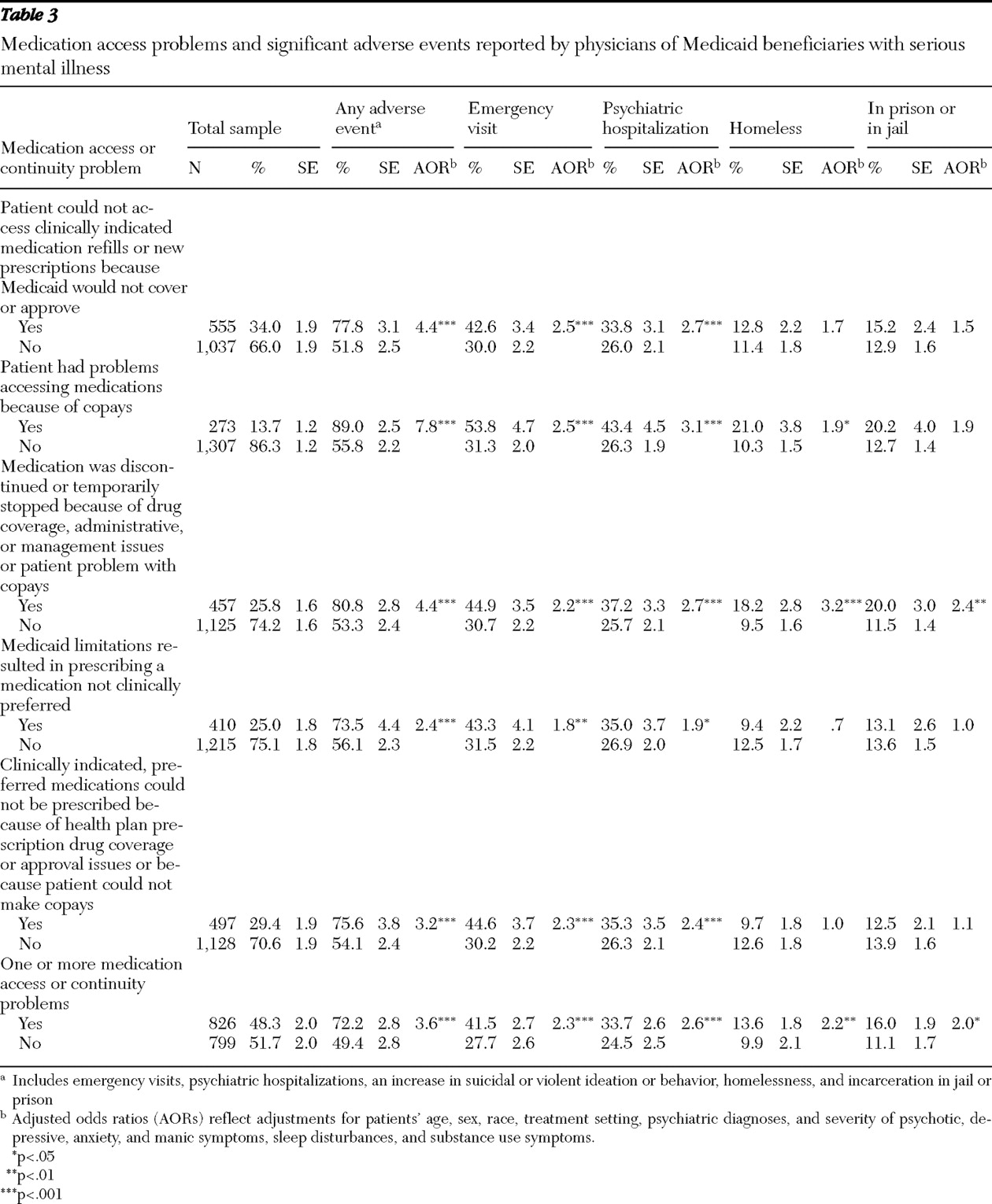

Approximately half the Medicaid patients were reported by their physician to have experienced at least one medication access or continuity problem, with one-quarter discontinuing or temporarily stopping their medications because of drug coverage, prescription drug utilization management, or copayment issues. Reported rates of medication access problems varied substantially across states, ranging from 27.1% to 64.7% of sampled patients. Clinician-reported adverse events, which were strongly associated with medication access problems, also varied significantly across states, from 45.1% to 70.0%.

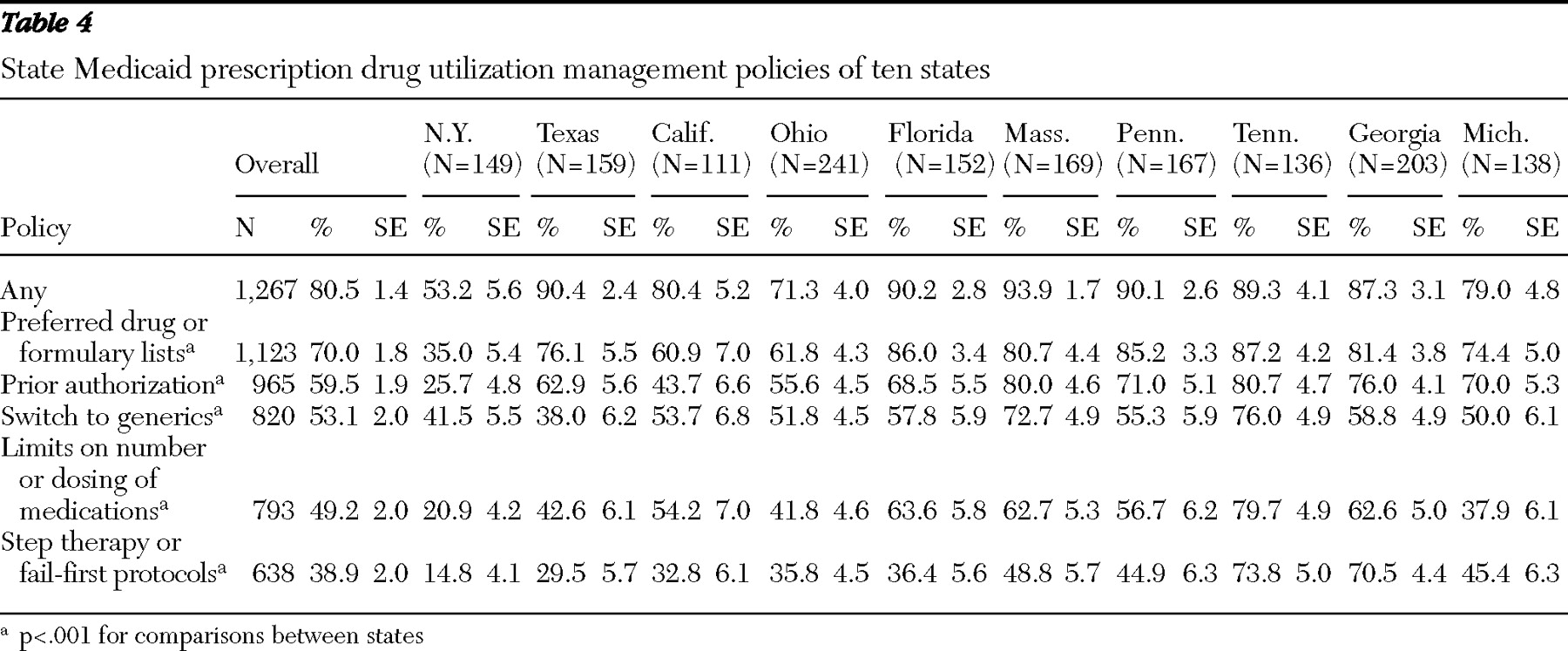

States with the highest rates of prescription drug utilization management had significantly higher medication access problems. With adjustment for patient case mix, Medicaid patients in states with the highest rates of medication access problems had 2.3 times greater likelihood of experiencing adverse events compared with patients in states with the lowest rates of access problems. Overall, the prescription drug policies in New York, Texas, and California warrant careful consideration, because they appeared to have a favorable impact on medication access and continuity and on adverse events. Patients in these states generally had significantly lower rates of having the prescription drug utilization management features we studied (including step therapy and fail-first protocols, limits on the number or dosing of medications, generic requirements, prior authorization, and preferred drug or formulary lists) apply to their care, compared with patients in the other states. Other state policies and factors may also be important. For example, better communication through interagency state information systems, more effective policies for waiving copayments, and prompter responses to prior authorization or appeals and exemption requests may also play a role in the lower observed rates of medication access problems and adverse events in these states.

Our study showed a strong, consistent pattern in which all the clinician-reported prescription drug utilization management policies and all the medication access problems studied were highly associated with significant adverse events. Patients reported to have a medication access problem were 3.6 times more likely than patients without access problems to experience an adverse event. Although rates of access problems in this study were generally lower than in our previous study of psychiatric patients who were dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare Part D (

11 ), the patterns of associations were highly similar. The transition of patients with dual eligibility to Medicare Part D caused significant problems for states, which may have contributed to access problems observed in this study.

Although prior research has identified significant opportunities for management strategies to improve quality and continuity of psychopharmacologic treatment (

16,

17,

18,

19 ), this study indicated that current Medicaid prescription drug management features as reported by physicians were not associated with enhanced continuity of medication. Patients reported to be subject to prescription drug utilization management policies had 9.7 times greater odds of having a medication access problem. Medicaid prescription drug utilization management features—such as prior authorization, preferred drug lists, step therapy, and limits on the number and dosing of medications—raise concerns about their effect on quality and continuity of care, given their strong associations with medication access problems, discontinuations, and adverse events. Our data are consistent with prior research indicating that prescription drug utilization management strategies may have significant cost implications; medication access problems have been associated with greater health care services utilization and costs (

12,

13,

20 ), as well as costs to the social services sector (for example, unemployment and workers' disability and compensation associated with impaired functional status) and criminal justice sector. Given significant research highlighting the challenges of medication adherence in this seriously ill and vulnerable population (

21,

22,

23 ) and the deleterious clinical and other consequences of discontinuing or switching psychopharmacologic medications (

22,

24,

25,

26,

27 ), these findings raise important concerns, particularly given the clinical challenges of restabilizing patients who relapse.

The high rates at which patients were reported not to be able to access clinically indicated, preferred medications because of drug coverage or management issues (affecting 29.4% of patients) or to get medication refills or new prescriptions because they were not covered or approved (34.0%) are of particular concern. It is noteworthy that for 25% of patients, clinicians reported prescribing a medication not clinically preferred because drug coverage or management issues prevented them from doing so and that 20.3% of physicians reported changing or discontinuing medications rather than pursuing exceptions or appeals, possibly because of administrative burdens (

28 ).

Prescription drug utilization management strategies that are based primarily on cost (

29 ) rather than on clinical considerations, such as patients' symptomatology, comorbidities, and prior treatment history and response, as well as the therapeutic risks and benefits of different medications, can result in suboptimal care and pose serious risks to patients (

9,

10,

30 ). Psychopharmacologic medications within a class (such as antidepressants, antipsychotic medications, anticonvulsants, or antianxiety medications) are not directly interchangeable. Psychiatric patients generally have differential responses and tolerance or side effect reactions to different medications within a class. Patients with psychiatric illnesses often do not respond to their initial medication but do respond to subsequent trials with a different medication within the same or different class (

30 ). Although the impact of prescription drug utilization management varies depending on the drug and available alternatives, access to a full range of medications facilitates clinical management for this population. Especially worrisome are policies that could lead to medication discontinuations or treatment gaps among stabilized patients, which affected one-quarter of the patents in this study. Fail-first policies requiring documentation within current or past claims databases of failing to improve with a preferred medication can also have major unintended consequences. Such policies may require repeating a medication trial in which a patient previously did poorly or switching a clinically stable patient's medication, which may result in patient relapse or other adverse consequences.

Treatment protocols for evidence-based prescription drug utilization management, such as the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (

31 ), offer potential to improve outcomes of care. Prescription drug utilization management strategies should be based on evidence-based, patient-centered, clinically appropriate care management strategies and rendered in "real time" (without delay) to minimize disruptions in continuity of medication. Continued investments in comparative clinical effectiveness studies and publicly available databases of results of clinical trials are needed to inform evidence-based treatment protocols (

32,

33,

34,

35 ). More effective information systems are also needed to better utilize existing Medicaid administrative data to systematically evaluate medication patterns and outcomes and correlate findings with prescription drug utilization management policies (

36 ).

The association between requirements to switch to generics and increased adverse events raises concerns. This study did not, however, distinguish between requirements to switch to the same versus different generic compounds. If generic medications are true bioequivalents to branded products, one would not expect differential treatment responses. In a seriously ill, cognitively impaired population, switching to generics may create confusion among patients (

9 ), which may be associated with dosing or administration changes and result in medication discontinuations. Further investigation is needed to understand this dynamic.

Our findings that psychiatric patients with Medicaid coverage that places limits on the number or dosing of medications had higher rates of adverse events are consistent with prior research (

11,

12,

13,

14,

20 ). Although dosing limits may provide some clinical safety protections for patients, there may be clinical risks to psychiatric patients, particularly for those prescribed second-generation antipsychotics, given that the upper dosing limits have not been well established (

30 ).

The finding that one in seven patients was reported to have problems accessing medications because of copayments is troubling, particularly because this consumer issue frequently does not come to clinicians' attention (

37 ). States should strengthen policies and pharmacy practices to waive copayments for Medicaid patients for whom copayments provide a financial barrier to clinically needed medications, particularly for beneficiaries with severe mental illness who are at risk of decompensation and adverse events.

States should consider other best practices to improve the management and continuity of prescription drugs for this population. The use of medication support and adherence strategies shown to be effective in assertive community treatment models (

23,

38,

39 ) should be explored. This includes ordering and delivering medications to patients, providing education about medications, and monitoring medication compliance and side effects. Disease management strategies (

40 ) and more effective use of technology, such as pill boxes with paging systems, have also been suggested to enhance medication continuity (

41 ).