In Canada, social services and social assistance play a significant role in the public support of persons with mental illness. Public and community agencies pay for housing, medical services not covered under Medicare (for noninsured services, such as medications), and other living expenses either directly or in the form of grants. There is little information in Canada on the magnitude of these expenditures. Given the recommended expansion of mental health services by various commissions in Canada (

1 ) and Alberta (

2 ), budgeting and planning for additional services will require such information.

Two major public sources of social assistance for the population in Alberta with severe mental illness are the federal government's Canada Pension Plan-Disability Benefits (CPP-DB) and the Alberta Services' Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH) programs. We measured the expenditures generated by these two programs to support community-dwelling persons with mental illness in Alberta.

Methods

In Canada most mental health services (inpatient care, physician visits, and community mental health services) are provided through public (provincial) sources. For persons over age 65, outpatient prescription drugs for most conditions are provided by provincial governments. There is limited public coverage for mental health medications for other persons (mostly for persons with low incomes). Social assistance is not covered under the traditional Medicare health plans.

The CPP-DB program is designed for persons who have worked and contributed to the CPP and who have a minimum level of annual CPP contributions (

3 ). A person who qualifies for CPP-DB benefits by reason of mental illness must have a prolonged and severe mental disability, as determined by a physician. Recipients receive a fixed amount per month ($388 Canadian in 2005) plus an amount that is based on the recipient's prior employment-based contributions. The maximum payment in 2005 was $1,010 Canadian per month. CPP, which is operated from within the federal government department Social Development Canada, maintains a database of all recipients. At the request of the authors, the CPP Disability Policy Branch of Social Development Canada searched its beneficiary database for all CPP-DB beneficiaries who were Alberta residents in 2005 and 2006 and who were certified as having a severe and prolonged mental disability. Because of confidentiality restrictions, a further breakdown of data was not available. Data were obtained for the number of beneficiaries and average monthly benefit. CPP-DB covers the working-age (under age 65) population.

The Alberta AISH program is designed for persons with a severe and permanent disability who cannot work because of it (

4 ). AISH is open to all residents of Alberta, and there are no prior work restrictions. AISH thus covers a gap that was left out by CPP-DB coverage, in that it includes those who have not worked or contributed to CPP. An AISH applicant must apply for benefits and meet income restrictions. A physician must certify that the person has a severe and permanent disability. Although the disability is assumed to be permanent, recipients' assets are reviewed annually. Recipients receive a monthly living allowance, up to a maximum ($950 Canadian monthly in 2006), and health benefits for noninsured items such as prescription drugs, dental services, and eye care (

5 ). AISH deducts current income, including CPP-DB payments, from the income support payment. Alberta Seniors and Community Support maintains a database of all AISH beneficiaries. At the request of the authors, the ministry queried its database and provided data by age group on the number of AISH beneficiaries who were certified as having severe mental illness and the amount paid for income support and medical expenses.

Social assistance was compared with total public mental health expenditures in the province. These costs were estimated for the following services: inpatient and outpatient services in general hospitals, physician-provided services, inpatient and outpatient services in psychiatric facilities, and services in community mental health centers. All services received by persons with psychiatric diagnoses were identified for the population. Unit costs in the form of hospital per diem costs, outpatient visit costs, and costs of physician visits were assigned to these services, as reported by Block and colleagues (

6 ). The result was a measure of total mental health care expenditures that were paid for by the provincial health plan.

This study received ethics approval from the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board.

Results

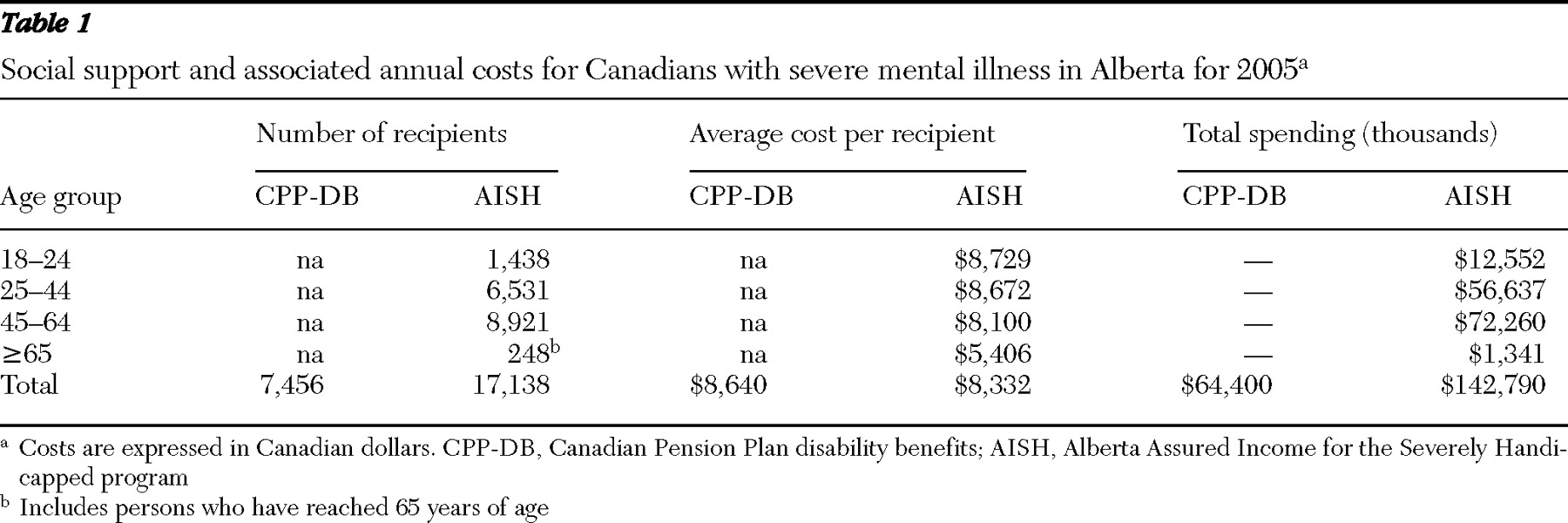

In total 7,456 persons with severe and permanent mental illness received CPP-DB payments in 2005. A total of 17,138 persons had severe mental illness and received AISH payments. A breakdown by age group is shown in

Table 1 along with annual CPP-DB and AISH benefits.

In total, CPP-DB benefits amounted to $64.4 million Canadian. The total value of AISH supplemental income benefits was $142.8 million Canadian. In total, AISH income supplements plus CPP-DB support for the population with severe mental illness was $207 million Canadian. This amount can be compared with the cost of mental health services. In 2005, the total cost for persons in all adult groups up to the age of 65 was $405 million Canadian (per the Alberta Mental Health Board, internal communication). The ratio of social support to provincial mental health services spending (excluding supplemental health service payments) was about 50%. Noninsured medical services, such as drugs (which are not covered under the provincial health plan proper), would add $53.2 million to the $405 million Canadian, about one-eighth of provincial mental health costs for adults.

Discussion and conclusions

A limitation of this study is that the data we obtained were highly aggregated, and in some cases (as with data on federal payments) we could not obtain sufficient data to obtain a full picture by age group of the role of transfer payments, or health care payments provided to the province from the federal transfer program. We also could not obtain data on recipients' incomes, which would have provided a clearer picture of financial status in comparison with social assistance. Given the magnitude of the social issue of providing care for persons with severe mental illness, the role of government benefits should be studied in more detail. Whenever a government-payer perspective or a financial-need approach is taken, these costs should be factored into the analysis.

The total of social assistance for Albertans amounted to about one-half the value of all mental health care services for adults under 65 funded through the provincial health plan ($405 million Canadian). These services are paid for by the federal and provincial governments in Alberta.

We focused on cash benefits for the Canadian population with severe mental illness. Previous studies on mental health care costs (

7,

8,

9 ) have focused on resource use and costs of resources, which is appropriate for comparing how resources are used (

10 ). However, public policy is also about equity—the economic burden of mental illness and public payments to ameliorate them. From the public perspective, transfer payments to persons in need are an important issue, especially considering the magnitude of these payments. If severe mental illness could be prevented, the government and the public would realize significant savings in the form of reduced transfer payments. By delaying the onset, minimizing the impact, or even preventing mental disorders, considerable cost savings conceivably would be made. These savings would affect funding that the province is currently receiving in the form of federally funded health transfer payments.