People with schizophrenia consistently report some impairment in their performance of daily activities (

1,

2 ). They often complain about the effects of cognitive difficulties, such as attention and memory problems, on their daily life (

3 ). Many perceive that being involved in daily activities supports a sense of competence and pleasure (

4 ) and that this influences their quality of life (

5,

6 ). Consequently, independent living and ability to perform daily activities are identified as treatment outcome priorities by persons with schizophrenia and are major criteria for recovery from this disorder (

7,

8 ).

Studies using performance-based assessments of functional capacity, such as the Test of Adaptive Behavior in Schizophrenia (

9 ) and the UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment (

10 ) and its brief version (

11 ), have found that functional capacity is associated with other global measures of functional outcome and predicts residential independence (

9,

10,

11 ). If performance of daily activities is important for residential independence and the quality of life of persons with schizophrenia, then more specific information on the limitations that impede their performance is needed.

Unfortunately, the small number of studies that have focused on functional limitations provide insufficient information on the observable behaviors affecting the mastery and competence of daily activities. This gap can be partly attributed to the daily-activities assessments used for global indictors of performance (

12,

13,

14,

15,

16 ). When more specific information was obtained with these assessments, methodological limitations restricted the generalizability of results (

17 ). These studies are therefore limited in their usefulness to guide rehabilitation interventions for persons with schizophrenia.

To establish appropriate treatment goals and interventions for these clients, it is mandatory not only to identify the functional limitations that have the most impact on performance of daily tasks but also to gain an understanding of the variability of functional limitations within a group of persons with similar psychiatric diagnoses (

18 ). Taking these considerations and the limitations of previous studies into account, we were guided for this study by two main questions. First, in daily task performance, what are the functional limitations among persons with schizophrenia? Second, do subgroups of participants have similar profiles based on the functional limitations revealed during the performance of a daily task?

Results

Fifty-two (63%) participants were men, with a mean±SD age of 41.70±9.90 years. Fifty-seven (69%) were unemployed, and 40 (49%) were living independently, alone in either an apartment or a room. The average number of years of education was 11.71±2.90 years. Seventy-five participants (91%) were Caucasian, one (1%) was Asian, two (2%) were Haitian, and four (5%) were African.

Functional limitations in the group of participants

The PRPP system revealed a number of errors committed by the participants at stage 1 of this assessment. The most common errors were accuracy errors (13.71±5.82 errors). These were noted when an attempt to complete a step in the meal preparation became problematic or when the quality of the outcome was questionable. Other types of errors were less frequent (repetition errors, .52±.87; omission errors, 1.68±1.59; and timing errors, .73±1.27). Having the dishes ready at the same time was problematic for 32 (39%) participants, who took longer than the acceptable delay, and 37 (45%) participants did not choose to start the task with the dish that took the longest to prepare (the cake).

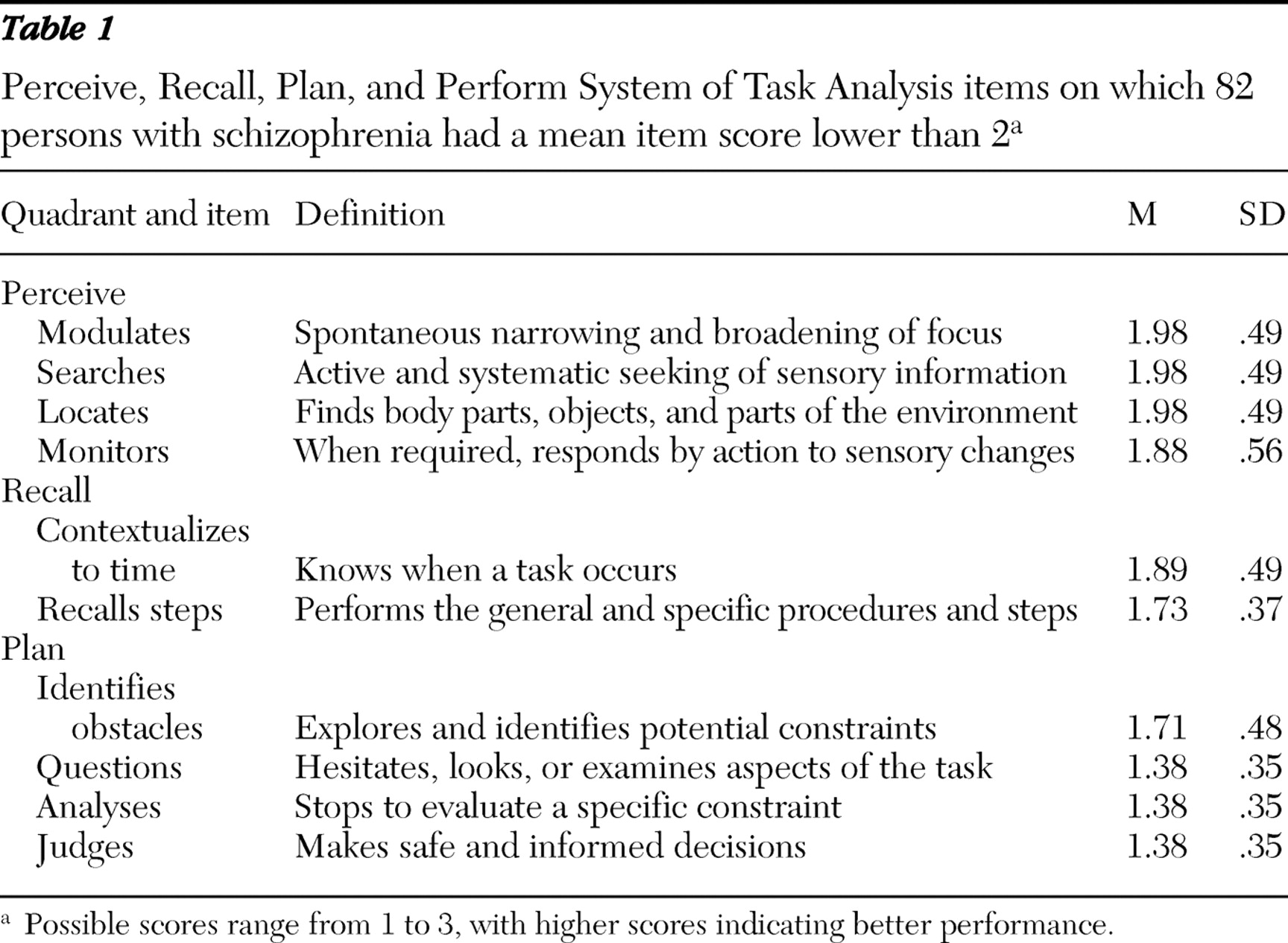

When these errors were analyzed in stage 2 of the PRPP system, difficulties in the plan and perceive quadrant descriptors, as well as in a number of recall quadrant descriptors, were most significant (

Table 1 ). Descriptors such as "modulates," "searches," and "recalls steps," to name a few, obtained mean scores below 2 out of a maximum score of 3.

Subgroups with similar profiles of functional limitations

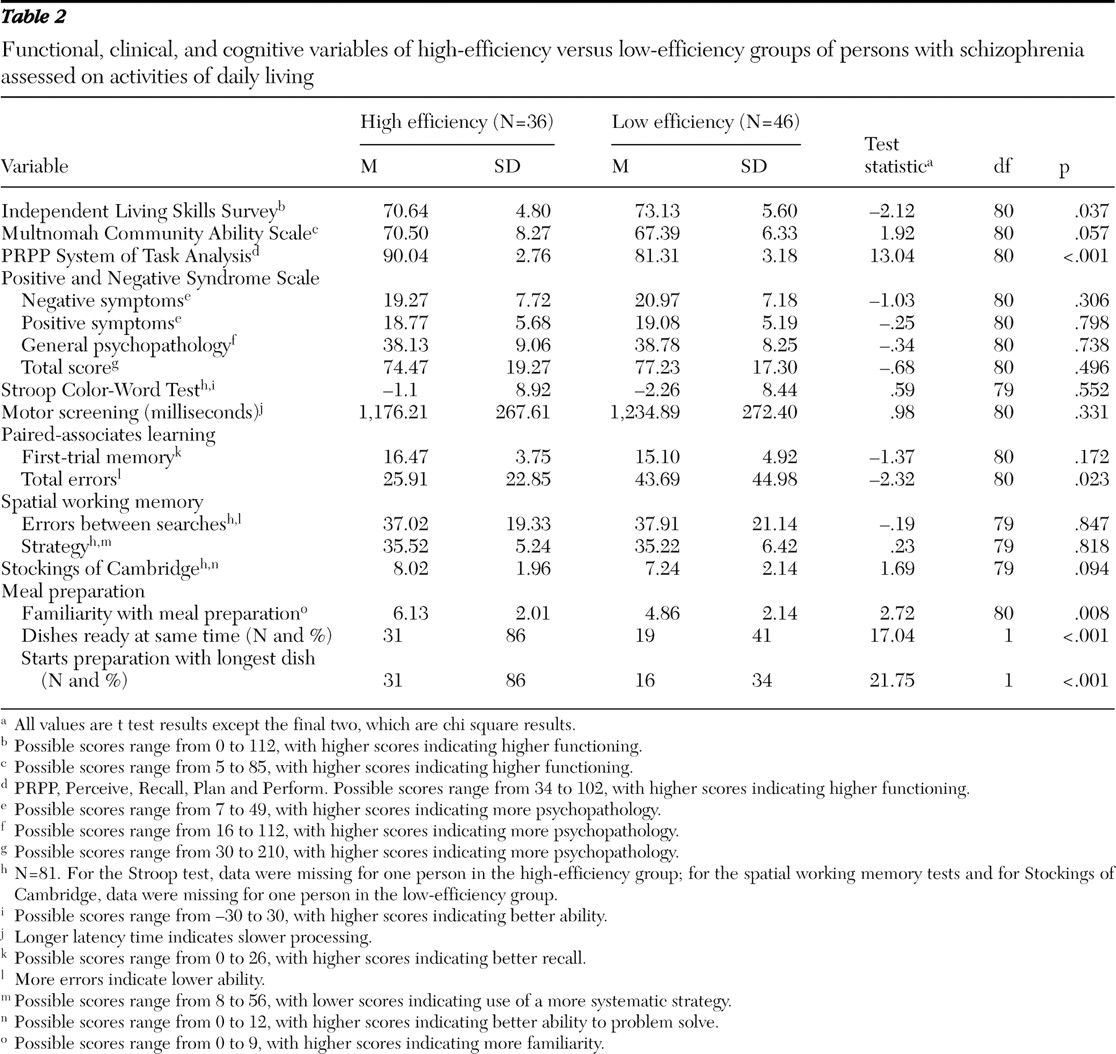

The high-efficiency group included 36 participants, and the low-efficiency group included 46 participants. Results from the comparison of these two groups on main variables are presented in

Table 2 . The high-efficiency group differed significantly from the low-efficiency group on all functional variables. Both groups also differed on the proportion of persons living independently: significantly more persons were independent in their housing in the high-efficiency group (25 independent versus 11 dependent; 69% of group independent) than in the low-efficiency group (15 independent versus 31 dependent; 33% of group independent) (

χ 2 =10.96, df=1, p=.001).

The high- and low-efficiency groups differed significantly on the PAL visual memory test, specifically on the learning scores (total errors). There were no significant differences between these two groups on the severity of symptoms, gender proportions, age, years of education, and time to psychiatric follow-up.

Because familiarity with meal preparation was significantly different for both groups, and familiarity was thought to possibly affect performance on this daily task, a generalized linear model was tested to control for the effect of familiarity on PRPP system scores. High-efficiency group scores were still significantly different from low-efficiency group scores on PRPP system total scores ( χ 2 =114.05, df=1, p<.001) and on the perceive ( χ 2 =23.93, df=1, p<.001), recall ( χ 2 =86.77, df=1, p<.001), plan ( χ 2 =89.24, df=1, p<.001), and perform quadrants ( χ 2 =45.68, df=1, p<.001).

Discussion

This study was designed to explore functional limitations in the context of task performance by persons with schizophrenia and whether different profiles are defined by these functional limitations. This study was different from previous studies of functional capacity of persons with schizophrenia—some of which also included a cooking task (

9,

14,

16,

17 )—in that the description of limitations included specific information-processing skills. This level of detail was made possible with the use of a performance-based assessment that is skill oriented, the PRPP system of task analysis, which uses a cognitive task analysis. Moreover, results from this study suggest that the information obtained about these limitations closely reflects real-world functioning. Participants who belonged to the high-efficiency group retained residential independence for the most part and had more autonomous community tenure than participants who belonged to the low-efficiency group. Hence, this performance-based assessment captured the "here and now" level of capacity, notwithstanding practice or experience with this meal preparation task.

Not unexpectedly, the participants had difficulties in the different stages of information processing. Limitations in skills such as searching, locating, recalling steps, and identifying obstacles had an impact on the execution of steps in the meal preparation task. Selective attention and visual search deficits have been consistently reported among persons with schizophrenia undergoing neuropsychological testing (

31,

32,

33 ). Behaviors related to decision-making, problem-solving, and error-monitoring abilities have been reported to be deficient among persons with schizophrenia (

34,

35,

36 ). Findings in this study suggest that functional limitations identified during a performance-based assessment may present a more ecological perspective of the difficulties encountered by these persons.

Problems in the perform quadrant of the PRPP were less frequent and less severe than in the other quadrants for this sample. The group had less difficulty to start (initiate), continue, and persist in the task, and we observed almost no perseverative behaviors (problems with "stop"). It is possible that this type of structured task, with specific instructions and with a given level of complexity, did not elicit problems related to initiation, effort, motivation, and persistence that are known to be problematic for some people with schizophrenia (

9,

37,

38 ).

The results regarding the differences between the high- and low-efficiency groups highlight the importance of one specific cognitive characteristic. Only one neuropsychological test, the visuospatial associative learning test, differentiated the high-efficiency group from the low-efficiency group, with the high-efficiency group having better scores on this test. These results suggest that the capacity to memorize and to learn is one of the key characteristics of functional capacity and that a greater capacity to retain information may increase the chances for better community tenure. These findings are in line with the research literature on cognition and community functioning that emphasizes the importance of assessing long-term memory and learning potential, which evaluates learning as it occurs within the assessment session, for community functioning (

39 ).

Similar results were obtained in another study. Stip and collaborators (

40 ) used neuropsychological tests of attention, memory, and executive function to compare persons with schizophrenia, who were grouped on the basis of their performance on daily tasks and on their level of residential autonomy. As in our study, they found that only the long-term memory test differentiated the groups and that no significant differences were apparent between the groups on the executive function tests. The authors suggested that the most autonomous persons may have developed specific mnemonics and strategies to help them negotiate day-to-day problems, as could have been the case in this investigation.

Findings from this study should be considered in regard to further development of rehabilitation interventions and strategies. If this performance-based assessment is helpful in capturing how limitations affect task performance, then it may be useful to target these specific problematic skills in rehabilitation interventions. Moreover, interventions could be developed to further support the generalization of these skills to a variety of tasks. For example, teaching and training of processing skills such as "searches and locates" could be integrated into actual or new strategies for daily living skills. Findings from this study tend to support the importance of learning ability relative to functional capacity and real-world outcomes, such as the greater degree of residential independence in the community. Authors have suggested specific approaches that take into account the impact of these types of deficits on the design of procedures to enhance learning, such as errorless learning strategies and modeling (

41 ). Recently, learning potential has been recognized as contributing to the prediction of rehabilitation outcome (

42 ) and to work skills acquisition (

43 ).

One limitation of this study is the relatively high number of comparisons and tests, which creates an elevated risk of type I error. Our study was considered to be at the exploratory level; therefore, the analyses for which the significance level was relatively low may be best viewed as needing further exploration and research. At one of the sites, the occupational therapist conducted the cognitive and functional assessments with some participants because other evaluators were unavailable, because of room scheduling, or to accommodate participants' availability. However, the occupational therapist was aware of the potential risk of bias; also, the computerized cognitive assessment was thought to diminish the risk of bias because results were calculated by the computer program and were not known before the end of data collection. As for functional assessment, the PRPP system task analysis grid developed for this study was, therefore, especially useful to avoid bias.

Not surprisingly, the classification into high and low efficiency according to the PRPP system scores did not perfectly discriminate between persons who lived dependently versus independently. Although performance efficiency in meal preparation was helpful to differentiate the level of housing independence of the participants, obviously more daily tasks should be assessed before determining the need for supervision and the level of within-community functioning of persons with schizophrenia. Also, different types of supervision are offered by health services organizations, therefore enabling more dependent persons to live on their own. Other problems, such as substance abuse, nonadherence to treatment, and absence of family members or social network, may be reasons for requiring a more structured environment.