Risk of physical and sexual assault varies by sociodemographic factors, such as gender and race or ethnicity (

1 ). According to estimates from one study of 16,005 community-dwelling adults, approximately one-half of U.S. women and nearly two-thirds of men were physically assaulted during childhood, and 17.6% of the women reported that they had been the victim of a completed or attempted rape at some time in their life (

2 ). A substantial proportion of the U.S. population has dealt with violence in childhood, adulthood, or both (

2 ).

Little is known about relationships between nonsexual assault and mental disorders in primary care populations. In a study of female primary care patients, a history of domestic violence significantly increased the likelihood of meeting criteria for PTSD, depressive disorder, suicide attempt, and illicit drug use (

10 ). A history of rape in adulthood also increased the odds of depression, PTSD, and suicide attempt.

Methods

The study was conducted at the Associates in Internal Medicine (AIM) practice of New York-Presbyterian Hospital (Columbia University Medical Center) in New York City between December 2001 and January 2003. AIM is the faculty and resident group practice of the Division of General Medicine at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University Medical Center. AIM provides primary care to approximately 18,000 adult patients from the surrounding northern Manhattan community each year.

The institutional review boards of the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center and the New York State Psychiatric Institute approved the study protocol, including the Spanish translation of data forms. All participants provided informed consent.

Participant eligibility

A systematic sample of adult patients seeking primary care who consecutively presented to the AIM practice was invited to participate. Eligible patients were aged 18 to 70 years, had made at least one prior visit to the practice, could speak and understand Spanish or English, and were waiting for a scheduled face-to-face contact with their primary care physician. Patients were excluded from the study if their current health status prohibited completion of the survey forms.

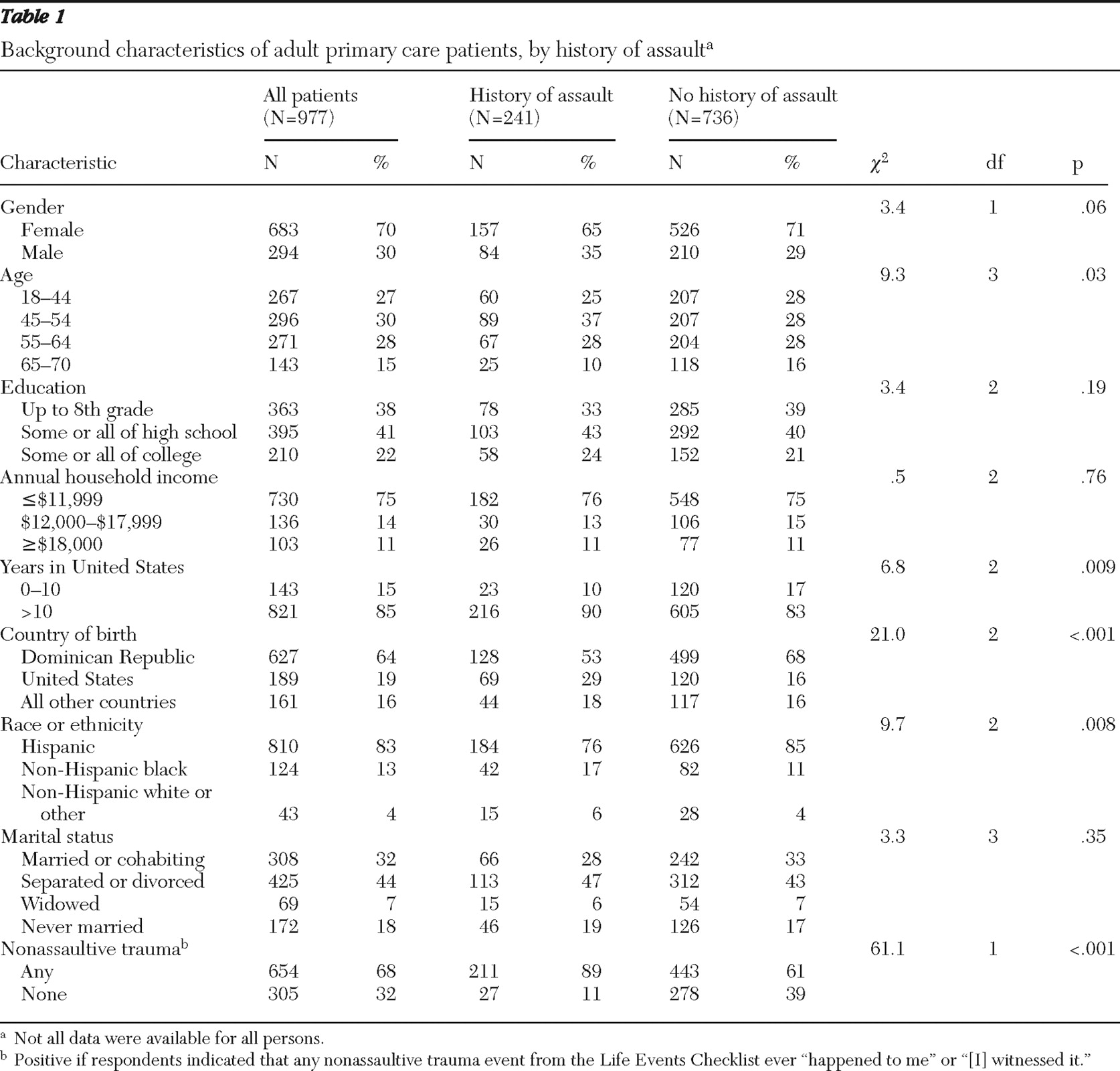

Assessment of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

The survey forms were translated from English to Spanish and back-translated by a bilingual team of mental health professionals.

All participants completed a sociodemographic history form to assess age, sex, race or ethnicity, marital status, educational achievement, and annual household income.

The Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) (

12 ), which uses diagnostic criteria from the

DSM-IV, was used to assess current symptoms of major depression, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and past-year alcohol use disorder. Drug use disorders were assessed with a module patterned after the PRIME-MD alcohol use disorder module. PTSD was assessed with the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (

13 ).

Participants also completed the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (

14 ). Participants who endorsed seven or more total lifetime manic symptoms with two or more co-occurring symptoms resulting in moderate or serious functional impairment were characterized as having a history of bipolar disorder (

12 ). Among participants who screened positive for having current major depression on the PRIME-MD PHQ, those with a history of bipolar disorder were classified as having current bipolar depression and those without a history of bipolar disorder were classified as having current unipolar depression.

A 19-item set of questions from the Life Events Checklist (LEC) (

4 ) was used to assess lifetime history of stressful events. Three of these questions were used to create an "assault" variable. These questions asked about lifetime history of physical assault ("for example, being attacked, hit, slapped, kicked, or beaten up"), assault with a weapon ("for example, being shot, stabbed, or threatened with a knife, gun, or bomb"), and sexual assault ("rape, attempted rape, made to perform any type of sexual act through force or threat of harm"). If a participant endorsed any of these three questions with a response of "[It] happened to me," she or he was considered to have a lifetime history of assault. Lifetime history of nonassaultive trauma was ascertained by a response of "[It] happened to me" or "[I] witnessed it" to any of the LEC items denoting nonassaultive events, such as natural disaster, fire or explosion, exposure to toxin, combat or captivity, transportation and other serious accidents, life-threatening illness or injury to self or family member, and sudden violent death or unexpected death of someone close.

Recruitment

A total of 3,807 patients were approached, of whom 169 (4%) refused solicitation. Of the 3,638 who were prescreened, 2,291 (63%) were ineligible to participate. Inclusion criteria most frequently unmet were not being scheduled for a visit with a primary care physician (N=1,294, 56%), not being between 18 and 70 years old (N=767, 33%), and not having made a previous visit to the practice (N=382, 17%). It was less common for patients to be excluded because they were unable to complete the survey forms because of poor physical health (N=76, 3%) or cognitive impairment (N=37, 2%). Of the 1,347 who met eligibility criteria, 1,157 (86%) consented to participate, and of these, 977 (85%) provided sufficient information to be classified with respect to history of assault.

Analytic strategy

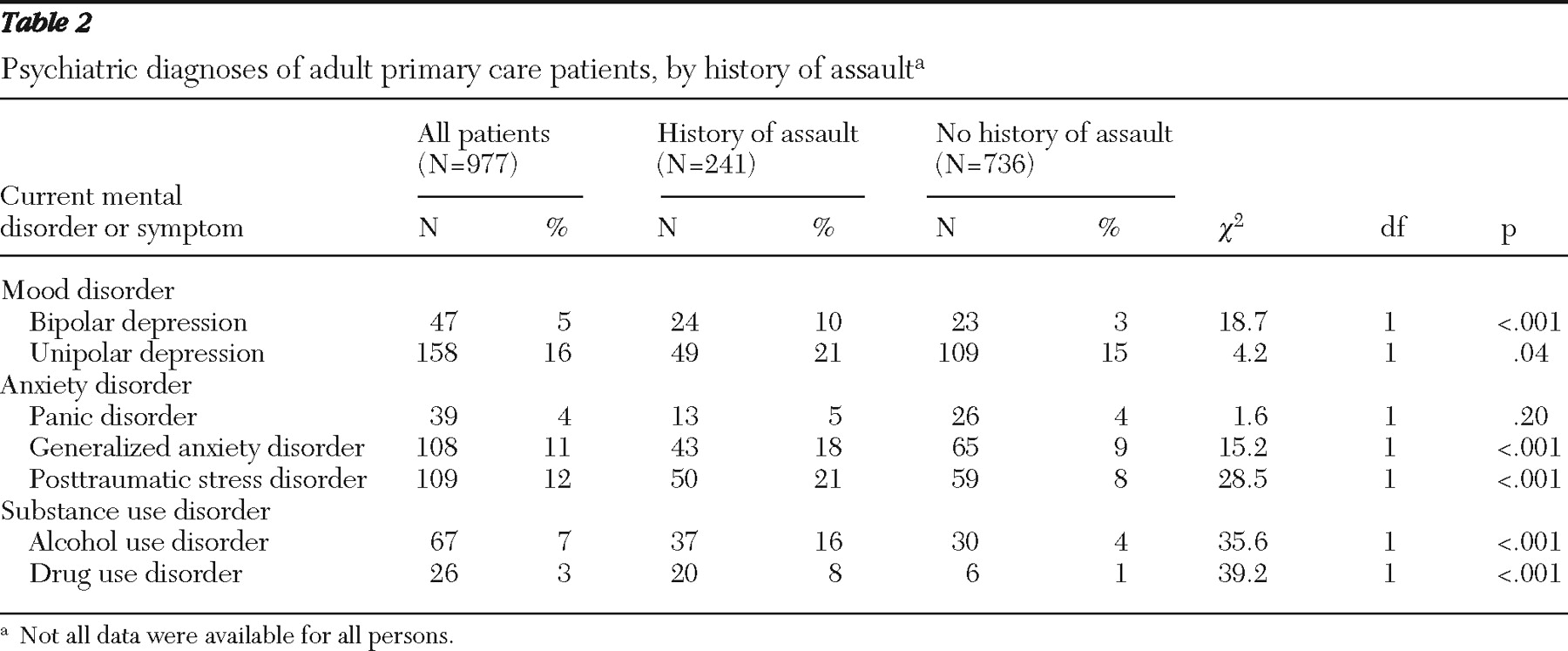

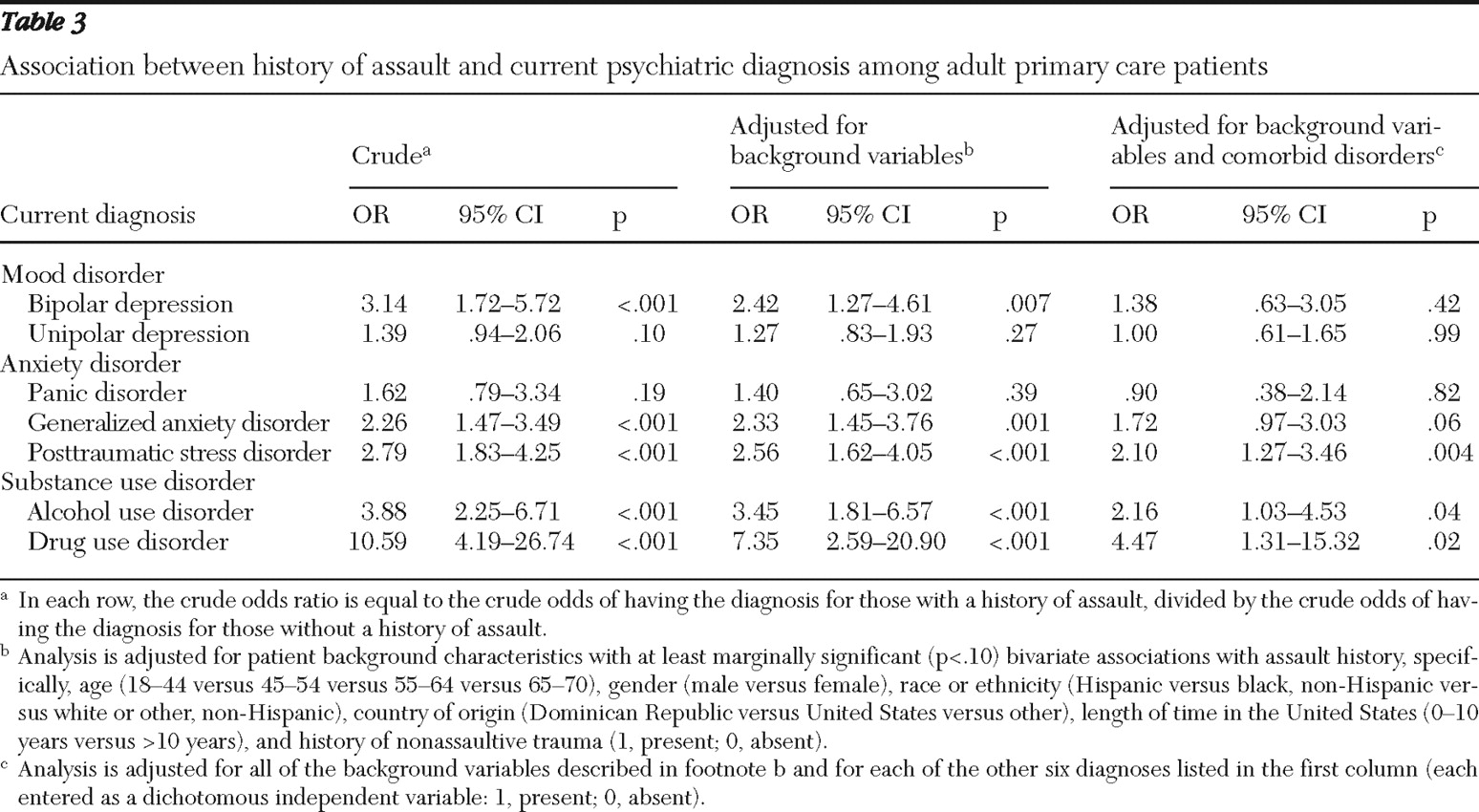

Patients were first partitioned on the basis of a lifetime history of assault. The two patient groups were compared with respect to sociodemographic characteristics, and mental disorders. Comparisons between patient groups on categorical variables were made with the chi square test. Logistic regression analyses were used to examine the associations of each mental disorder with lifetime assault while controlling for selected sociodemographic characteristics and comorbid diagnoses. The alpha value was set at .05 (two-tailed).

Discussion

Twenty-five percent of a sample of adult primary care patients who consecutively presented to an urban group general medical practice reported a lifetime history of assault. This is somewhat lower than rates from earlier studies: 38% (

15 ) and 52% (

2 ). Differences in demographic composition may account for the differing assault rates between the studies. Although our sample was predominantly older women of Hispanic ancestry, the two previous studies had samples that were predominantly young adult males who were white, non-Hispanic. Breslau and colleagues (

15 ) demonstrated that men, the young, and members of ethnic and racial minority groups residing in urban areas have higher lifetime risk of exposure to assaultive violence, compared with women, older persons, and residents of middle-class communities.

In the study presented here, there were significant relationships between a history of assault and positive screens for mental disorders. The mental disorders that bore the strongest unique associations with a history of assault were substance use disorders and PTSD. The interpretation of these correlations should take into account the cross-sectional design.

A cross-sectional assessment of mental disorder with a retrospective assessment of assault raises questions concerning the direction of causality. It was not possible to establish through this study whether patients with an assault history were at greater risk of a mental disorder or whether they had a preexisting mental disorder that could have predisposed them to subsequent assault. For example, a participant with a substance use disorder could be at greater risk of assault when under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Drug use has been associated with anger, impulsivity, and violence (

16,

17 ). Illegal drug use can lead to violent behavior as a result of irritability from drug withdrawal, and decreased vigilance of the user may increase risk of victimization (

18 ).

The study results have important implications for the delivery of primary care and specialty mental health services to urban, low-income, ethnic minority primary care populations. Strong associations between assault and mental disorders suggest that a history of assault should alert primary care clinicians in these settings to an increased risk of several mental disorders. Yet, because the average internal medicine office visit lasts just 21.5 minutes (

19 ), the pace of primary care practice likely affords few opportunities to perform detailed mental health assessments or inquire about recent assault or other traumatic events.

Brief screening instruments for common mental disorders (

20,

21,

22 ) can simplify the preliminary evaluation of mental health problems in primary care. Screening alone, however, is unlikely to improve patient outcomes. Greater collaboration is needed between primary care physicians and specialty mental health professionals. In a recent survey, approximately two-thirds of primary care physicians reported that they could not get outpatient mental health care for their patients with mental health problems (

23 ). In fact, barriers to accessing medical services are approximately twice as common for mental health care as they are for other types of medical services (

23 ).

Development of referral networks and close collaborative relationships between primary care physicians and mental health specialists may be needed to smooth the transition of high-risk patients into specialty mental health care. Collaborative care (

24 ) offers one promising model for delivering mental health services to primary care patients who are victims of assault. It involves a nurse practitioner or case manager who assists with the management of mental health problems through structured delivery of interventions, mechanisms to foster communication between primary care clinicians and mental health specialists, and collection and sharing of information on patient progress.

The observation that lifetime history of assault significantly increased the risk of PTSD and substance use disorders suggests that consideration should also be given to brief self-report screens for history of assault (

25,

26 ) during the intake process at primary care services for low-income populations. In many practice settings, however, such screening may not be feasible because of competing demands for other aspects of the assessment. Previous research suggests that most female primary care patients are not routinely assessed for abuse. Only 7% to 28% of female patients report being asked about abuse by health care professionals (

27,

28 ). According to one estimate, the average primary care physician would need to devote over seven hours of every working day just to deliver existing federally recommended screening and preventive services (

29 ). Because of the unlikelihood that screening for trauma will become standard in primary care in the near future, primary care physicians should remain alert for clinical indications of recent trauma. These may include multiple unexplained physical problems, persistent physical pain, or symptoms of irritable bowel (

30,

31 ).

This study has several limitations. As indicated, given the cross-sectional design, it is not possible to establish a causal link between a history of assault and development of the mental disorders. We also could not quantify the frequency or duration of participants' sexual or physical assault. These factors could undoubtedly influence the existence and severity of mental disorders. Survey nonresponse may have introduced selection biases that influence the strength of associations between a history of assault and mental disorders. The study sample was limited to patients aged 18–70 years who were waiting for a scheduled appointment with a primary care physician. The practice does not treat adolescents, and the psychometric properties of the mental health screens are less well established among older adults. The requirement for direct clinical contact follows our interest in patients who receive clinical attention. Because the study population was limited to mostly poor, urban, nonelderly Hispanic women with little education, the results may not generalize to other primary care populations or to the surrounding community population. The study population was limited to returning patients; therefore, results may not generalize to first-visit patients, who are logical candidates for lifetime trauma history assessments.

Rates of mental disorders were based on self-report screens, not on structured diagnostic interviews, which have greater validity. Differences between the assault and nonassault groups could be explained by other confounders—for example, other unmeasured traumas besides assault. Additionally, with the exception of bipolar disorder, current symptoms, not lifetime symptoms, of mental disorders were assessed. This could have excluded patients who may have had already resolved past episodes of depression that may have been correlated with a history of assault.