The book Asylum, Christopher Payne's memorialization of America's disappearing 19th century state hospitals, is subtitled Inside the Closed World of the State Mental Hospital. An alternate subtitle might have been, "Inside the Disappearing World of the Closed State Mental Hospital." Using photographs, Payne makes the point that the state hospital was a "closed world," but I think he overstates his case.

Pages 21–55 are exterior views of state hospitals. The photographs are stunning. Having seen many of the buildings myself, I can attest to the fact the views are selective (as well a photographer's portrayal should be) and yet true to life.

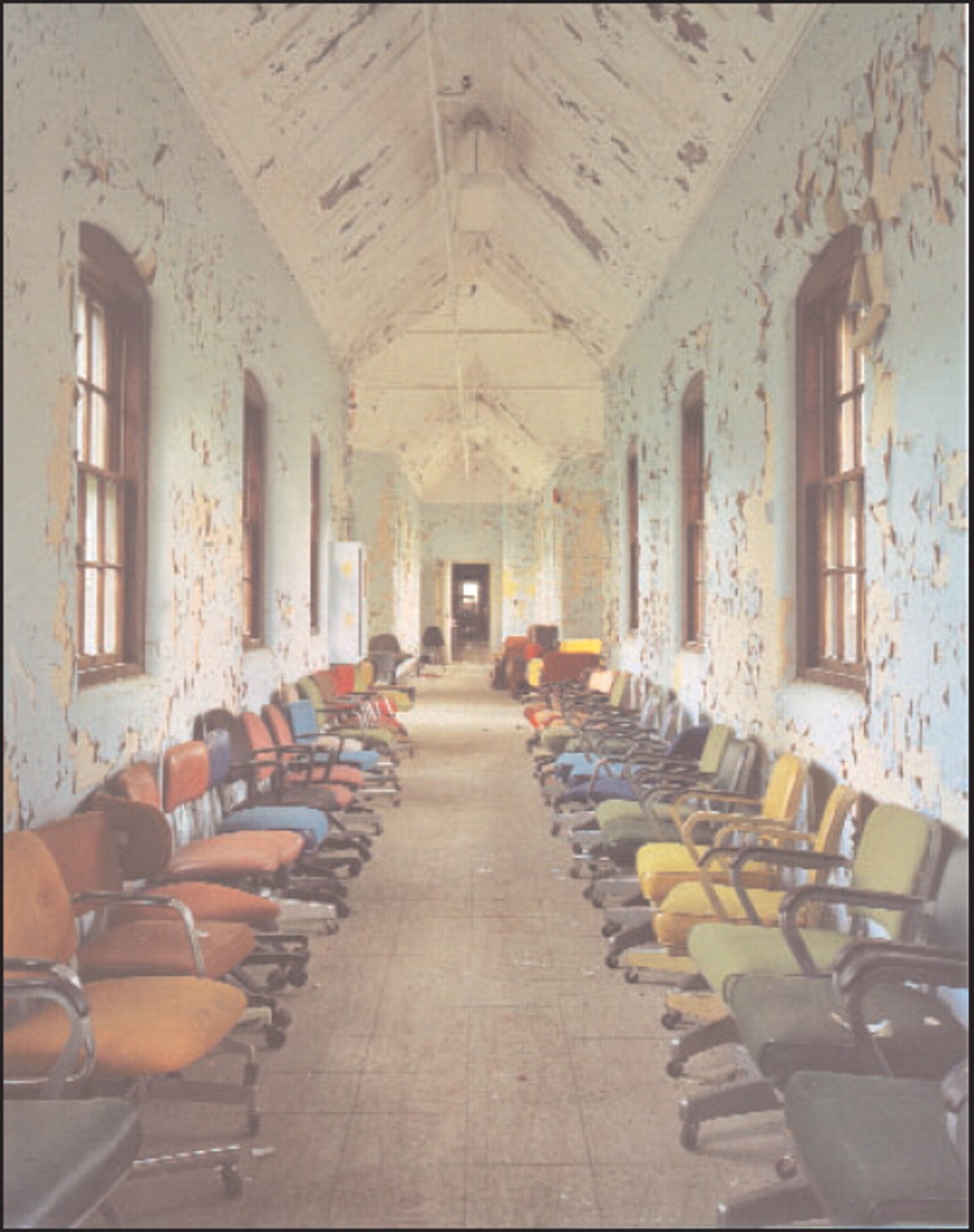

Pages 57–117 are interior views. These photographs are also stunning, a mixture of color and black-and-white. But here, I was caught up short. The images are all so neat, with virtually no images of human detritus. What of the people who inhabited these spaces? I have been through scores upon scores of abandoned state hospital wards, and on many the reminders that patients were once part of the picture are everywhere—strewn clothing, cups and soda cans, cleaning fluid bottles and mops, newspapers from the last day the ward was occupied. … Virtually none of this is in Payne's pictures. I kept asking myself, looking at image after image, "Who swept the floor?" Payne comments, "In all hospitals, the wards were fundamentally the same. … On their own, they are just hallways, but taken together they are symbols of a closed and isolated ward." From my eye and my experience, Payne's selection of images (with added housekeeping) distorts the remains of the state hospital to highlight this viewpoint.

Pages 118–201 contain striking photographs of interior and exterior shots, both black-and-white and color. This is the most successful section of the book, a moving portrayal of living at the state hospital, from daily activity through death. Without showing a single person—these are, after all, abandoned state hospitals—life pulsates in these pictures. This makes the second section, with its sterile corridors, all the more puzzling. In this third section, Payne refers to the state hospitals as "communities," a stark contrast to the prose that introduces the second section, quoted in part above.

The photographs of Asylum are verbally framed by introductory essays by Oliver Sacks and Payne and by an afterword from Payne. These essays are easy-to-read, simplified histories that, unfortunately, contain some historical inaccuracies. The transition from prose to photographs is made through four pages containing 25 images of state hospitals from old postcards and an image of the Creedmoor State Hospital census board from a day in March 1953: total census of 6,440 patients, of which 5,795 were inpatients, exceeding the hospital capacity by 1,653 patients.

Asylum is both a testimony to what we all lose as these state hospital buildings disappear from the American landscape and a reminder of what behemoth, self-contained institutions they were. The last photo before the afterword is of a poem written on a basement wall of Augusta State Hospital in Maine: "If my heart could speak, I'm sure it would say, I wish I were someplace else today.…"

In perusing these photographs, one's thoughts can drift beyond the conditions of state hospital buildings to the conditions of the services that state hospitals once provided. The reader is actually set up to do this, in part, by the Sacks essay. Community and contemporary inpatient services might well be in sorrier shape than the state hospital edifices. How many residents of the jails of Cook County (Illinois), Los Angeles County, and Rikers Island (New York) would not, when comparing their current environs with those of the former state hospitals during their period of operation, agree with President Franklin Pierce's description of them in his 1854 Veto Message: "munificent establishments of local beneficence"?

The reviewer reports no competing interests.