Over two million U.S. service members have been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan since America's engagement in the post-;September 11 "war on terrorism," approximately 27% of whom have been deployed more than once. Research suggests that the burden of mental disorders and symptoms, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorders, and depression, is high among service members within the first year of returning from these deployments (

1,

2,

3,

4,

5 ). Furthermore, with some notable exceptions (

6 ), research suggests a rise with time since deployment in the rate of psychiatric problems among U.S. service members and veterans (

3,

7,

8,

9,

10 ), which may indicate better problem detection and more psychiatric morbidity over time. Reports of increases in marital and occupational difficulties after military service in either Iraq or Afghanistan (Iraq-Afghanistan) (

1,

4,

11,

12 ) provide further evidence of postdeployment reintegration problems.

Research on postdeployment health problems among Iraq-Afghanistan war veterans is needed to inform the development and resourcing of health services. However, the existing research base has several limitations for health services planning. First, many prevalence studies are based primarily or exclusively on samples of active-duty Army personnel and therefore do not provide information about other types of service members (

9 ), including activated National Guard and reserve troops, who may face unique circumstances during and after their deployment (

3,

13 ). Second, most studies describing rates of psychiatric symptomatology have assessed service members within the year after returning from their deployment (

1,

3,

5,

8,

14,

15 ), leaving unexamined their long-term adjustment problems. Third, because most prior studies have focused on psychiatric disorders, we know relatively little about the functional problems that Iraq-Afghanistan veterans face as they attempt to reintegrate into their home communities. Veterans may perceive problems functioning at home, school, or work to be as important as or more important than symptom resolution (

16,

17 ). Last, the treatment preferences of this new generation of veterans, which differs from earlier cohorts of veterans in terms of age, education, and comfort with technology, is understudied (

18 ).

The secondary objective of this study was to explore associations between probable PTSD, reintegration problems, and treatment interests. PTSD is of particular concern because it is the most prevalent psychiatric disorder among returning combat troops and veterans (

1,

3,

4,

5,

14,

20,

21,

22 ). PTSD has also been associated with functional problems among veterans of previous wars (

23 ) and with aggressive and suicidal thoughts and behavior among Iraq-Afghanistan veterans (

3,

7,

13,

24 ). Furthermore, PTSD has a greater impact on quality-of-life outcomes than do mood and other anxiety disorders (

25,

26 ).

Methods

The Minneapolis VA Medical Center Subcommittee on Human Studies reviewed and approved all aspects of this research.

Sampling strategy

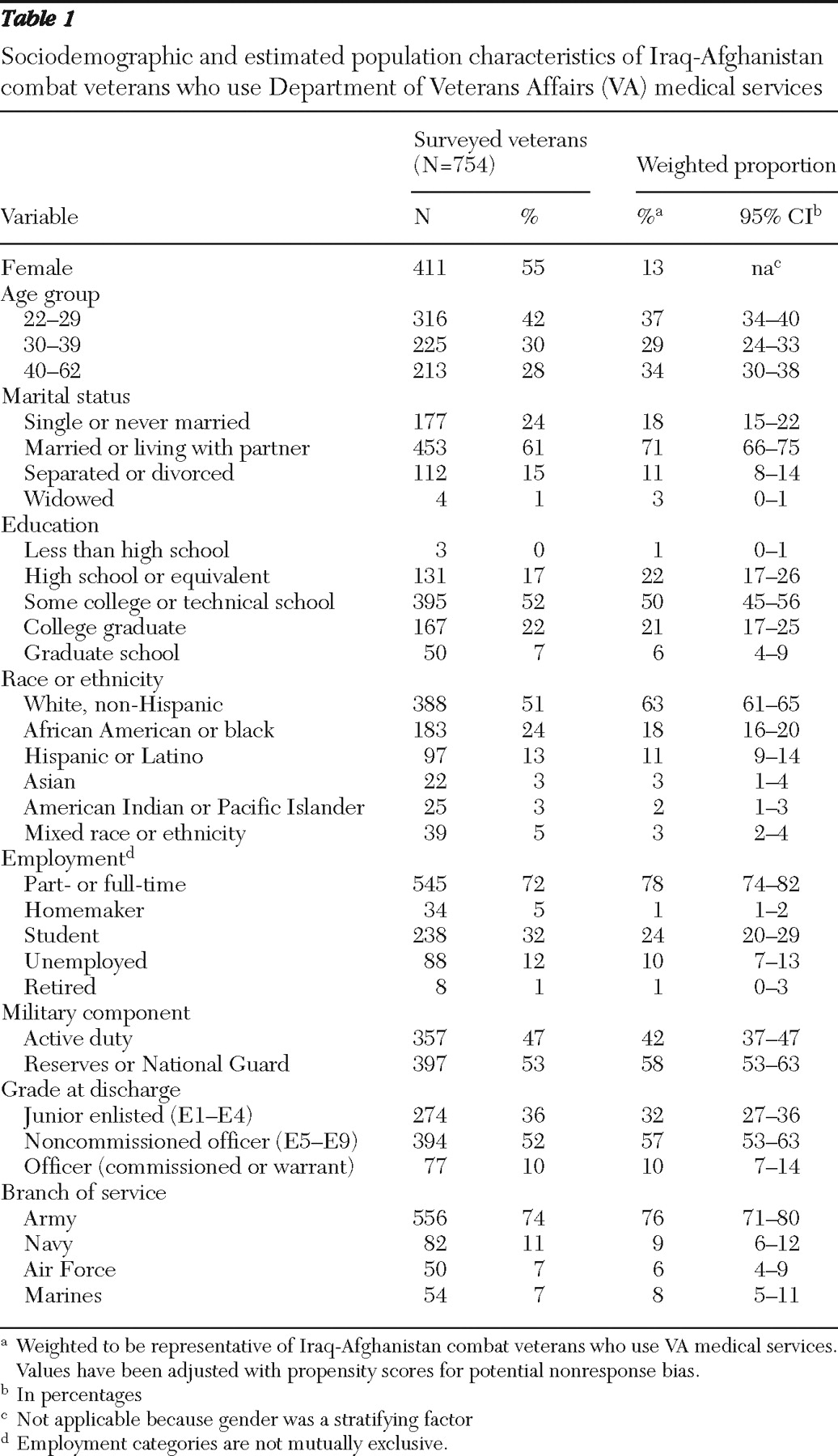

Our sampling frame included the 181,611 Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who made at least one visit to a VA facility within the continental United States between October 2003 and July 2007. This represents 60% of Iraq-Afghanistan veterans who used VA services within this time frame. The remaining 40% were not classified as combat veterans.

We used stratified random sampling without replacement. We selected this sampling strategy to increase the precision of our estimates and models. Because sampling from demographically more homogeneous groups produces estimates with smaller error variance than a simple random sample (

27 ), we sampled from strata that included veterans of the same race-ethnicity and gender who were living in geographically similar areas. To this end, we divided the United States into six regions (Northeast, Southeast, Upper Midwest, Southern Midwest, Northwest, and Pacific Coast). Each regional stratum was divided into four gender (male or female) and race (white or nonwhite) combinations. From each of the resulting 24 strata we randomly selected 55 Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans for recruitment (N=1,320). Because one-fifth of Iraq-Afghanistan veterans had missing race-ethnicity data, we randomly selected an additional 15 men and 15 women with missing race-ethnicity information from each of the six regions (N=180). Later, we used veterans' self-report to reclassify race and ethnicity and to verify deployment. We then constructed estimates using Horvitz-Thompson type estimators, with weights equal to the inverse of sample inclusion probabilities.

Of the 1,500 veterans originally identified for survey, 274 were excluded for the following reasons: deceased (N=8), veteran of other war eras (N=89), could not be located through U.S. Postal Service after three attempts (N=167), or currently redeployed to Iraq or Afghanistan (N=10). Of the 1,226 Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who remained eligible, 754 (62%) returned surveys by July 14, 2008.

Recruitment

Veterans received a prenotification letter describing the study, followed two weeks later by a cover letter, 12-page questionnaire, and $5 incentive. The cover letter reiterated the study's goals and described the risks, benefits, and voluntary nature of participation. Return of the survey signified veterans' consent to participate in the study. Nonresponders received a reminder letter and two more mailings of the questionnaire. Data were collected between April and July 2008.

VA administrative data

We used VA administrative databases to obtain the following sociodemographic information for both responders and nonresponders: age, gender, race-ethnicity, military component (active duty versus National Guard or reserve), receipt of service-related disability benefits (any benefits and benefits specifically for PTSD), use of VA mental health services within the past year (any versus none), and distance in miles to nearest VA and community-based outpatient clinics. We also extracted the past two years of the ICD-9-CM codes for PTSD, anxiety disorders other than PTSD, depression, substance use disorders (excluding nicotine dependence), psychoses, and traumatic brain injury.

Study questionnaire

The study questionnaire assessed veteran characteristics, physical and mental health, perceived community reintegration problems, and treatment interests and preferences regarding intervention service delivery (in person or over the Internet). The research team, which included clinicians with expertise in deployment-related readjustment problems and in measure development, developed the initial version of the questionnaire based on literature reviews, early findings from ongoing studies, and clinical experience. A focus group of one veteran and three active-duty service members provided the investigators with anonymous feedback on the content and format of the initial version of the survey. After incorporating this feedback, we pilot-tested the survey with a sample of 87 Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans. We finalized the survey after analyzing response patterns and reviewing participant comments in the comment section.

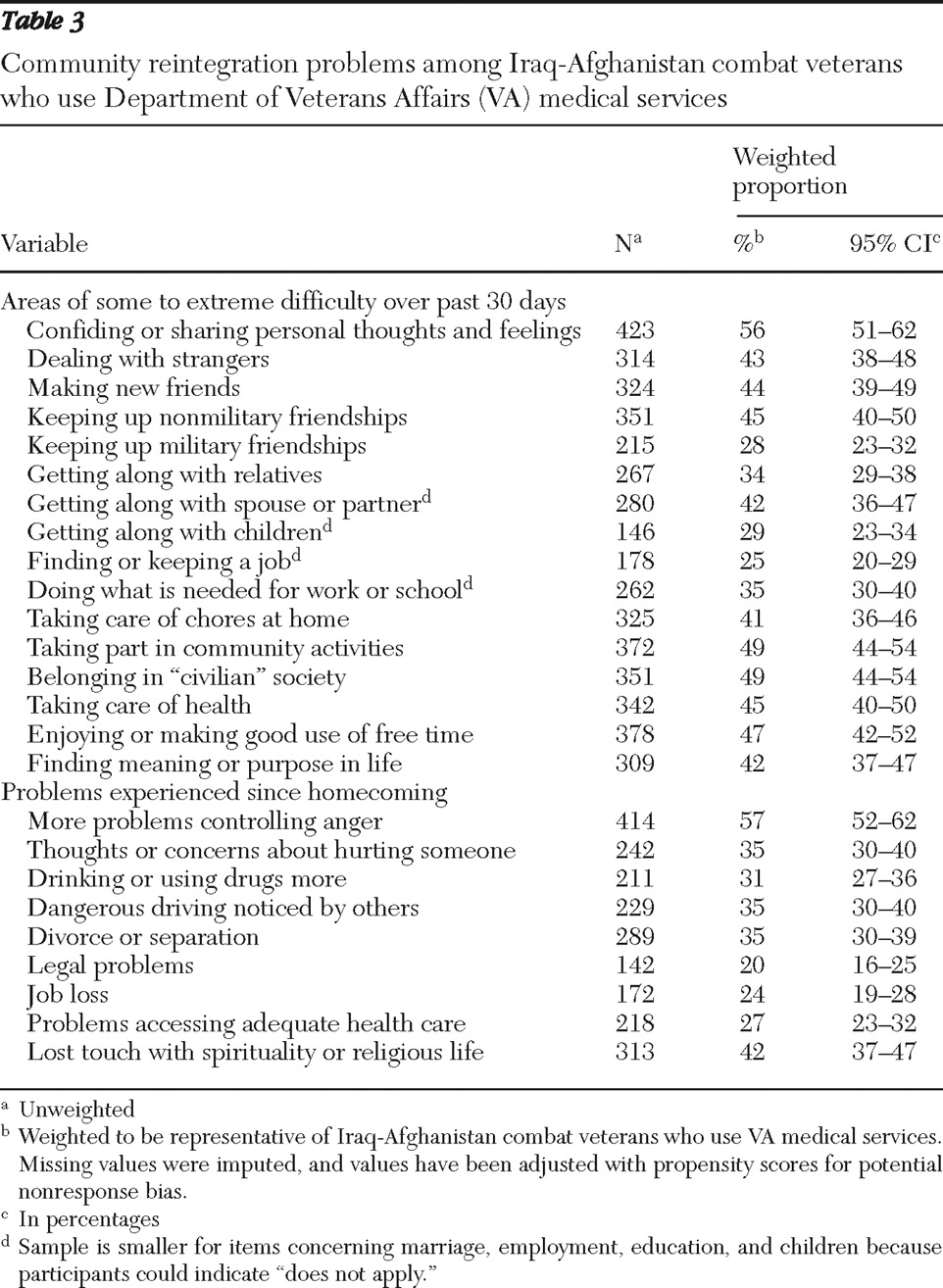

Community reintegration and treatment preferences

One item assessed overall difficulty in readjusting to civilian life over the past 30 days on a 5-point scale ranging from 1, no difficulty, to 5, extreme difficulty. Sixteen items assessed specific problems over the past 30 days in the following functional domains: social relations, eight items; productivity, three items; community participation, two items; perceived meaning in life, one item; and self-care and leisure activities, two items. Responses ranged from 1, no difficulty, to 5, extreme difficulty. Items were modified for relevance to this population from the social relations, life activities, and self-care domains of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II (

28 ), supplemented with content from the Community Integration Questionnaire and Community Integration Measure, which were developed for traumatic brain injury research (

29,

30 ). Internal consistency of these 16 items, as measured by Cronbach's coefficient alpha, was .95. Nine yes-no items were used to assess problem experiences since returning home from Iraq or Afghanistan, including four items on potentially harmful behaviors and one item each on divorce or separation, legal problems, job loss, problems accessing health care, and loss of spirituality or religious life.

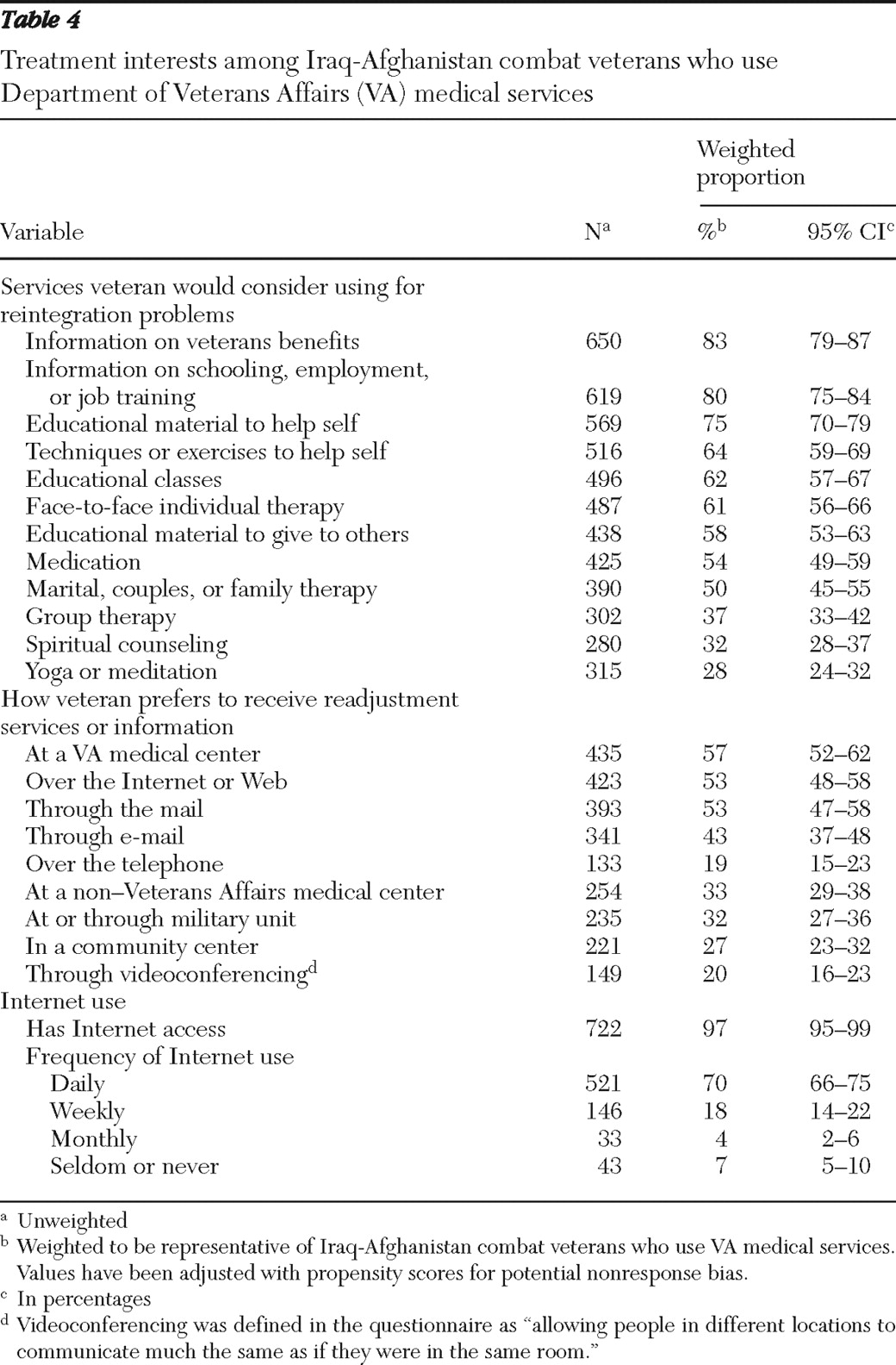

To assess interest in services for readjustment problems, participants checked individual items on a list of 12 possible services. They also indicated how they would want to receive information and services for community reintegration problems. In addition, because use of the Internet has become increasingly common for health care service delivery (

31,

32 ), we assessed access to the Internet and frequency of Internet use.

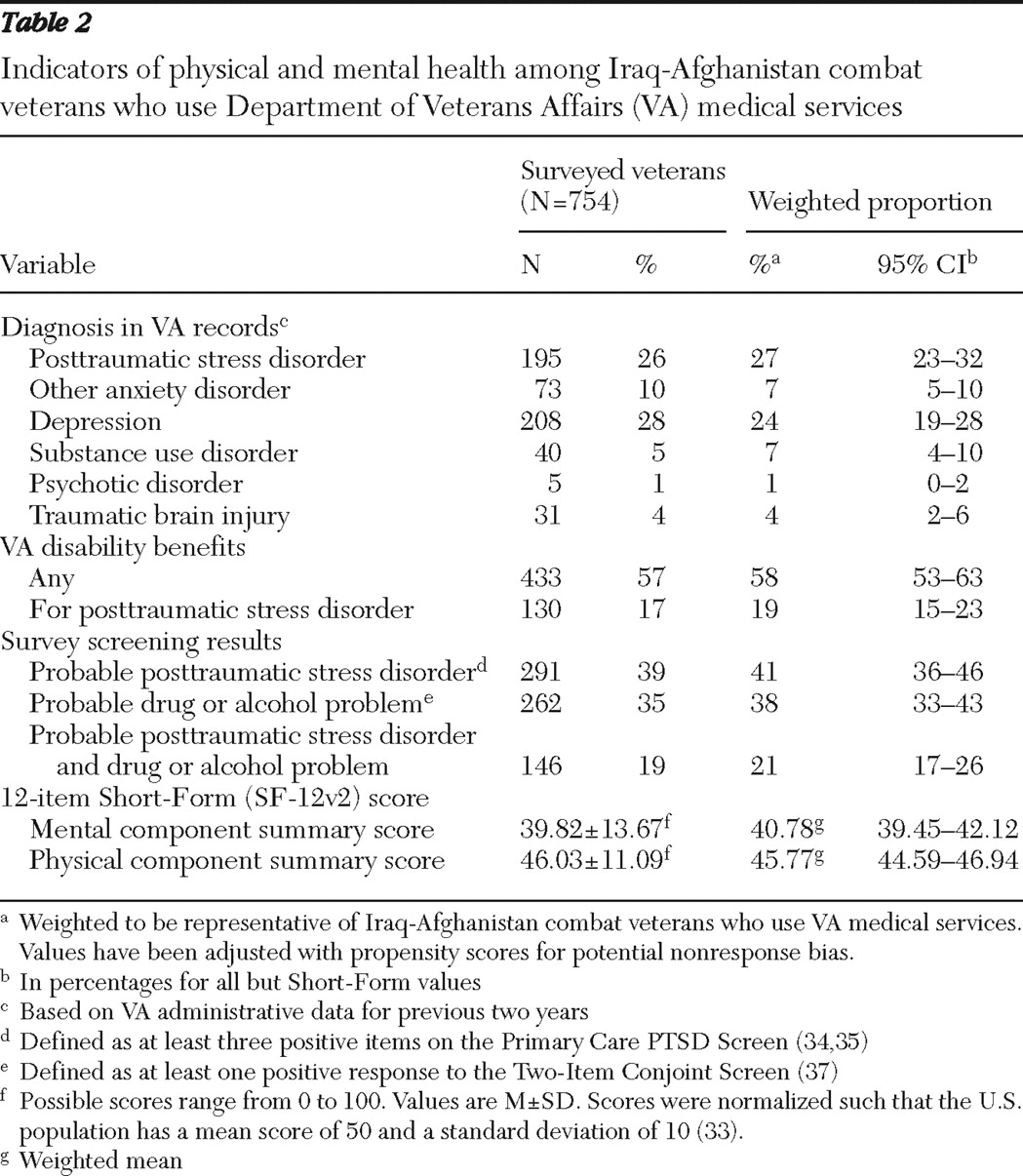

Physical and mental health

Overall physical and mental health status was assessed with the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12v2), with mental and physical health component summary scores normalized such that they could be compared with values obtained in the U.S. population, which has a mean score of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 (

33 ). To assess probable PTSD, we used the Primary Care PTSD Screen (

34 ), which is used by the VA and Department of Defense (DoD). A cutoff score of 3 yielded .76 sensitivity and .92 specificity for clinical PTSD in a sample of active-duty soldiers who returned from combat in Iraq (

35 ). We screened for alcohol and drug problems using the Two-Item Conjoint Screen (

36,

37 ). This screen is also included in the DoD Postdeployment Health Reassessments (

3 ). A cutoff score of 1 had .80 sensitivity and specificity among 18- to 59-year-old primary care patients (

37 ).

Statistical analysis

Prevalence and proportions were weighted to represent the population of Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who used VA medical services. We used stratified estimates weighted by the inverse of sample inclusion probabilities to calculate population parameter estimates and their standard errors (

27 ). Less than 3% of community reintegration items had missing values. Assuming that this degree of missing data depended only on the observed covariates, we imputed missing values using logistic regression methods for multiple imputations (

38 ). We used stratified logistic regression models to construct odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (

39 ) for community reintegration problems by probable PTSD status.Odds ratios were adjusted for demographic characteristics that preceded deployment, including age, gender, race-ethnicity, and military component. When comparing community reintegration problems among those with and without probable PTSD, we used a p value of <.002 as the threshold for statistical significance. Stratified Poisson regression was used to determine whether probable PTSD was associated with the number of community reintegration problems and the number of services of interest for community reintegration problems. All analyses were performed for responders and then adjusted for potential nonresponse bias based on administrative data available for both responders and nonresponders; adjustment was achieved by constructing response propensities and producing a weighted combination of within-propensity class estimates (

40 ). SAS, version 9.2, and R coding were used to perform the calculations.

Responders did not differ from nonresponders in diagnoses extracted from VA medical records, receipt of mental health services, distance to a VA or community-based outpatient clinic, service connection for any condition, service connection for PTSD, or race-ethnicity. Compared with nonresponders, responders were older, were more likely to be female, and were more likely to have been activated to Iraq or Afghanistan from the National Guard or reserves than from active duty. The decision to adjust for demographic characteristics that preceded deployment was made a priori to increase the precision of our estimates.

Discussion

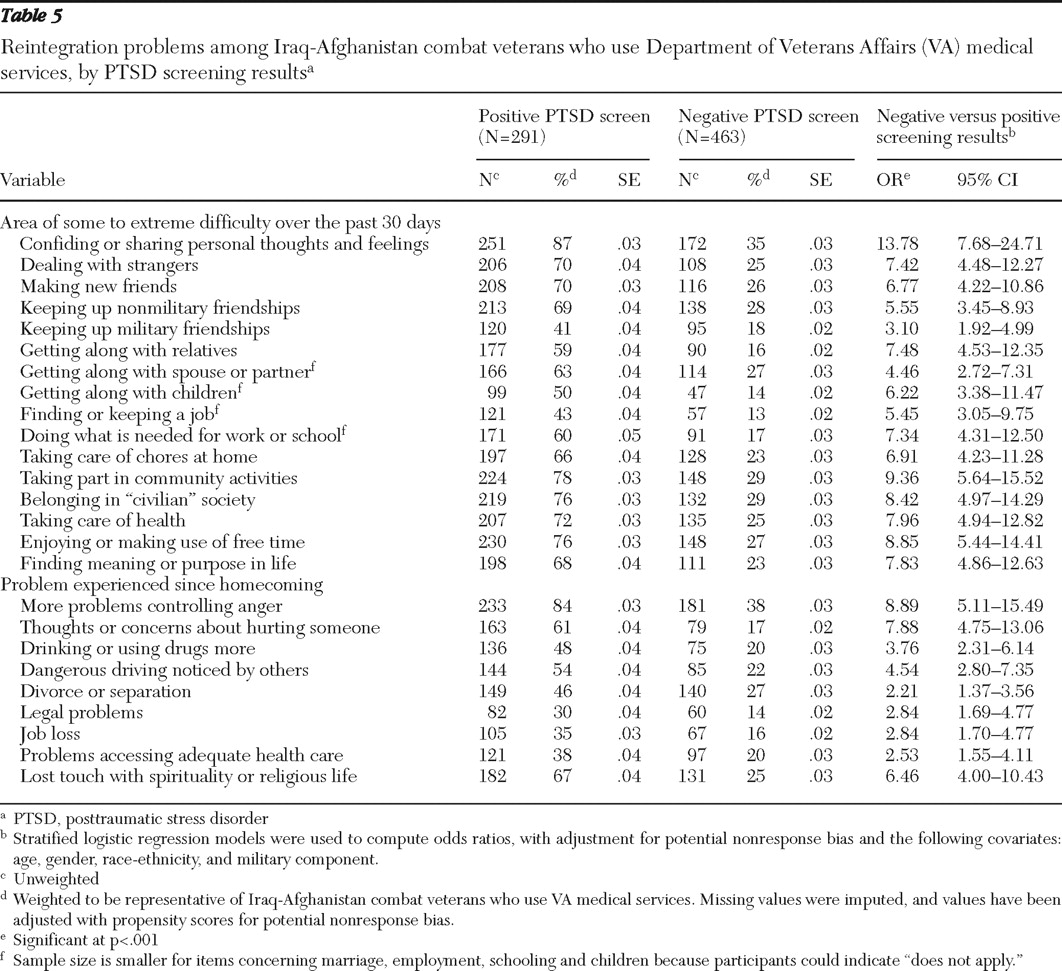

This is the first systematic study of community reintegration problems and associated treatment interests among Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who use VA medical care. More than one-half of this select population was struggling with anger control problems, and nearly one-third had engaged in behaviors that put themselves or others at risk since homecoming, such as dangerous driving and greater alcohol or drug use.

Not surprisingly, veterans with probable PTSD reported more reintegration problems and expressed interest in more kinds of services for reintegration problems than did veterans without probable PTSD. Thus this subgroup may need to be targeted more aggressively for community reintegration interventions. Regardless of PTSD status, however, Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans faced challenges in multiple domains of functioning and community involvement after deployment. Left untreated, these problems could have deleterious effects not only on the individual but also on his or her family, community, and society as a whole. We thought it hopeful that almost all of these veterans would like information or services that could help them with these problems. Because so many used the Internet frequently, Web-based applications may prove useful for delivering services and information to this newest cohort of war veterans. However, it is unknown whether treatment interest translates into treatment seeking. This is of concern because a significant proportion of individuals with common mental disorders do not seek professional help, even after they recognize the need (

41 ). Barriers to treatment initiation include attitudes and beliefs, financial and logistical problems, system-level factors that limit access to services, and, among combat veterans, posttrauma experiences perceived as invalidating of their service (

1,

41,

42,

43 ).

Whether veterans have access to effective services to help with community reintegration problems is also uncertain. Although federal and state governments have implemented programs to promote community reintegration postdeployment, evidence of the effectiveness of these programs is lacking. Furthermore, although more than half of Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans had an interest in receiving readjustment services through a VA medical facility, not all VA health care providers have the training, skills, or time to assist veterans with the broad range of problems they reported. Many of the problems that veterans endorsed, including social functioning, employment issues, anger control, and spiritual struggles, fall outside the traditional scope of medical practice. VA mental health providers, who usually have the requisite skills to address these issues, may struggle to keep up with demand. Furthermore, it remains unknown whether evidence-based treatments for PTSD would lead to satisfactory improvements in functional and readjustment outcomes. Functional outcomes are not always included in PTSD trials, and results from some trials suggest that functional improvement does not always accompany symptom reduction (

44 ).

In contrast to the rate of PTSD diagnosis indicated in VA medical records, we identified a substantially higher rate based on responses to the Primary Care PTSD Screen (27% versus 41%, respectively). We do not know whether the medical record rate is more or less accurate than our survey screening rate. Before the post-September 11 "war on terror," PTSD was underdiagnosed in VA medical records, with provider detection of PTSD having 46.5% sensitivity and 96.6% specificity (

45 ). Research is warranted to determine whether PTSD is underrecognized among Iraq-Afghanistan veterans, despite use of a health care system that specializes in PTSD diagnosis and treatment.

The prevalence of probable PTSD identified through our survey exceeds that obtained in surveys of active-duty Army and Marines conducted within one year postdeployment (

1,

14 ) and a population-based telephone survey of military personnel conducted up to five years postdeployment (

6 ). However, prevalence of probable PTSD was lower than the rate reported in a study of veterans screened for PTSD at one VA facility using the same assessment instrument and cutoff score we used in our study (

46 ). One would expect PTSD to be more prevalent among treatment-seeking combat veterans, many of whom have service-related disabilities, than among veterans who are not seeking treatment. Also, our study differed from prior survey studies in terms of sampling strategy, measures, measurement context (research versus clinical), and time of assessment relative to deployment, which limits comparability. A recent study that used a dynamic mathematical model combined with data from the Iraq war estimated that the rate of PTSD among Iraq war veterans will approximate 35% (

47 ). This estimate takes into account the lag time between trauma exposure and symptom onset as well as the fact that many troops included in prevalence studies will have subsequent deployments.

There may have been important differences between survey responders and nonresponders that we were unable to identify using the VA administrative data. These unaccounted-for differences could have biased our population estimates. In addition, the study population included Iraq-Afghanistan veterans who use VA services and who were classified as combat veterans. At the time of this report, about 56% of Iraq-Afghanistan veterans were not enrolled in the VA, and of those enrolled, 40% were not classified as combat veterans. We speculate that the Iraq-Afghanistan veterans included in our sampling frame may carry a greater burden of illness than noncombatants and those who do not use the VA for health care. Because the VA is the largest single provider for returning combatants, it was important to focus our initial attention on this large and important group. However, it is unclear whether Iraq-Afghanistan veterans who receive care in the community have the same issues as those seeking VA care. Nonetheless, our findings provide a starting point for the types of issues that community providers should be alert for when treating Iraq-Afghanistan veterans.

Limitations associated with our questionnaire include use of a screening measure to identify probable PTSD rather than gold-standard diagnostic interviews. A study of Dutch Army troops found that self-report symptom measures overestimated the rate of PTSD relative to clinical interview (

48 ). Even in cases where our screening measure identified true cases of PTSD, we do not know whether the PTSD was related to combat in Iraq or Afghanistan or to other traumatic experiences. Evidence suggests that 9%–10% of service members screen positive for PTSD before deployment to Afghanistan or Iraq (

1,

49 ), underscoring the need to consider predeployment mental health when drawing conclusions based on these findings. Unfortunately, information on VA disability status was of limited use for verifying deployment-related PTSD in our sample because veterans may wait years to decades before filing a claim for PTSD, if they file at all (

50,

51 ), and we cannot assume that all veterans in our sample had filed PTSD claims. Also, there were important areas that we did not assess in this brief mail survey, including suicidal ideation and depression. Last, it was beyond the scope of this study to address questions concerning differences in community reintegration problems according to psychiatric diagnoses other than probable PTSD, any versus no psychiatric disorder, or by number and type of medical comorbidities. Future studies should address these limitations.

On the other hand, strengths of this study include our ability to provide population-based estimates for Iraq-Afghanistan combat veterans who receive VA medical care and use of a rich sampling frame to adjust for potential nonresponse bias. In addition, soldiers activated from the reserves and the National Guard, who are often underrepresented in research (

9 ), were well represented here.