Researchers who have studied the health care workforce have recognized that group- and staff-model health maintenance organizations (HMOs) may provide valuable clues about the future size and composition of the U.S. health care workforce (

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11). Most studies of clinical staffing have been limited to cross-sectional analyses and have not focused on the range of mental health professionals used to staff integrated HMOs. The bulk of the literature has examined the impact of managed care on physicians (

5,

6,

10), ignoring the impact of the managed care market on other professionals. Our data and analysis help fill this gap.

We begin by describing the current trends in mental health managed care. Then we present data on mental health staffing and mix of providers from a case study of two large staff- or group-model HMOs located in different Western states for the years 1992 to 1995. These staffing figures are then compared with those from a single behavioral health organization and with the ratio of providers per 100,000 population in the respective states where the HMOs are located. Finally the changes in ratios and distribution patterns of mental health professionals in the two HMOs are discussed.

Background

Integrated managed care organizations attempt to avoid fragmentation in the delivery of patient care, reduce utilization, and limit the organization's financial risk by the use of gatekeepers. This practice limits the number of contacts between specialty providers and patients (

12,

13). The use of gatekeepers, however, raises the concern of mental health providers that patients' access to appropriate mental health services may be curtailed (

14). In addition, whether primary care physicians or mental health professionals should function as gatekeepers for mental health care has been of concern.

The rise in contracting between managed care organizations, managed behavioral health care plans, and providers has been largely responsible for the recent changes in the organization of mental health care delivery. In these carve-out arrangements, the delivery or administration of mental health services is not integrated into the managed care organization's main benefit plan but is instead contracted separately to a managed behavioral health firm. Managed behavioral health firms may accept a prearranged payment to perform only management functions, or they may accept financial risks for providing all mental health services as part of the contract through capitation arrangements. In a 1997 national survey of behavioral health organizations and HMOs, Oss and associates (

15) found that 110.2 million members were enrolled in non-risk-bearing organizations and 58.4 million members were enrolled in risk-bearing organizations, which included risk-bearing behavioral health networks and mental health services within integrated HMOs.

All models have in common the use of utilization review and gatekeepers to contain cost and improve efficiency. Under managed care arrangements, control over services is being shifted from independent mental health providers to the managed care organizations that organize and deliver the care (

16,

17,

18).

As more providers and managed behavioral health plans assume the risk of capitation, organizations responsible for care delivery will have a strong financial incentive to utilize the mix of professional staff that is most cost-effective. Purchaser-driven price competition in the managed care industry has increased dramatically since 1990 and has served to motivate mature HMOs to implement clinical staffing innovations that reduce costs (

19).

Expected staffing changes in organizations that provide mental health services include the use of nonphysician mental health providers who act as economic substitutes or complements for physicians, including psychiatrists (

20). Economic substitution, in which one worker may perform certain duties of another worker, also occurs among mental health specialists. For example, clinical social workers may be substituted for doctoral-level psychologists in providing such services as counseling. The use of the term "substitution" is not meant to imply these providers are exactly alike. Moreover, researchers have pointed out concerns about the quality and appropriateness of care when lower-cost clinicians or primary care physicians are substituted for better-trained specialists (

21,

22). In contrast to substitution, complementary roles are roles one provider performs that are not commonly performed by another provider. For example, psychiatrists may prescribe medication and clinical social workers may be expert at case management; thus their roles complement each other.

Before the 1990s, physicians provided most care in managed care organizations. In recent years, managed care organizations have increased their use of nonphysician mental health providers. The appropriate degree of economic substitution of one type of provider for another remains controversial. However, the financial savings realized by using lower-paid nonphysician health professionals to deliver mental health services could also serve as an incentive for the development of a more collaborative medical practice. In such a practice each mental health provider would assume a special role in the delivery of care using his or her unique skills to meet the patient's mental health care needs (

23). The workforce dynamics we report in this paper suggest that notable changes are under way in the staffing of managed care organizations as they develop new configurations for the delivery of mental health services.

Case study

To examine the staffing of mental health professionals in integrated managed care systems, we collaborated with the Institute of Medicine to collect staffing data for the period from 1992 to 1995 from two large not- for-profit, well-established HMOs in two Western states. We studied examples of group- or staff-model organization because this model has been used as a prototype for efficient workforce staffing in the health care system (

2,

10,

24).

The two HMOs are located in separate metropolitan areas, each with a population of more than 1 million. Each HMO is located in a metropolitan market where price competition among health plans has intensified in recent years. Each is a full-service HMO that is capitated for all care, including mental health care, and thus fully at risk for such care.

The first (HMO A) is a group-model HMO that contracts with one large multispecialty medical group for most physician services, including psychiatry and behavioral health services. The second (HMO B) is a staff-model HMO that directly employs most of its physicians. Both organizations can be described as closed-panel HMOs in that most of their medical staff treat HMO members exclusively. However, each organization relies to some extent on outside physicians for emergency treatment and specialty services. Both HMOs are not-for-profit, mature organizations, each with more than 250,000 members. The two organizations are similar in the gender and age of their enrollees and in the percentage of enrollees in Medicare and Medicaid.

Because mental health care is increasingly delivered by managed behavioral health organizations through carve-out arrangements (

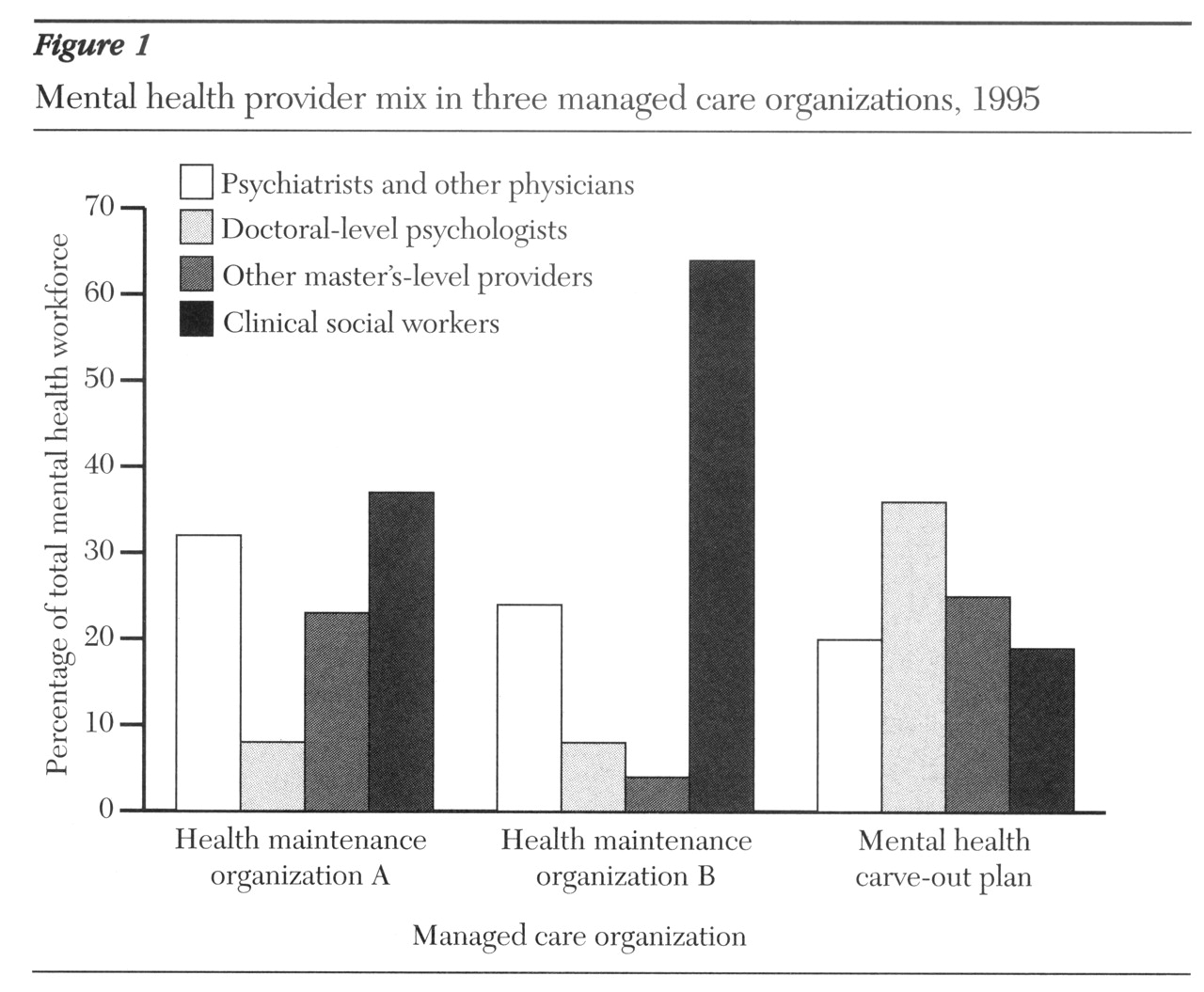

25), we also collected data on the mix of providers at one large behavioral health carve-out plan from the same area where HMO A is located. The plan provided data on the numbers of providers in each specialty. Data for only 1995 were available.

Data collection

Part of the data used in this analysis was collected in 1994 and 1995 by the Institute of Medicine to explore the future of primary care (

26). Surveys that requested detailed data on clinical staffing and organizational features over a three-year period (1992 through 1994) were mailed to 12 geographically dispersed, nonrandomly selected HMOs, two of which provided comprehensive data about staffing for mental health services provision. With the permission of the Institute of Medicine, we directly contacted the two HMOs selected for this study. We obtained additional information to fill gaps in the data reported to the Institute of Medicine, collected data for a fourth year (1995), and interviewed key executives within each organization.

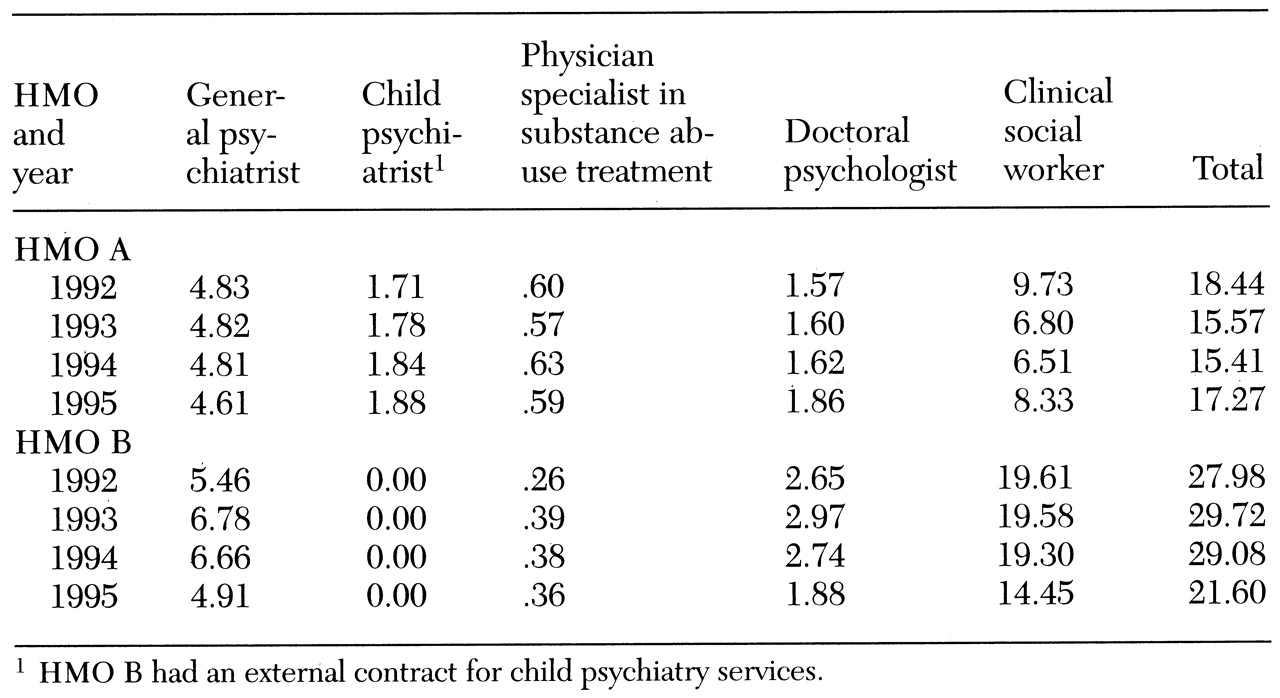

The HMO staffing figures presented here represent the average number of full-time-equivalent (FTE) clinical staff—those directly involved in patient care—for each calendar year. FTE figures were requested for psychiatrists and nonphysician mental health workers in the following categories: master's-level counselors, clinical social workers, doctoral-level psychologists, and clinical nurse specialists. We excluded physicians and other health professionals who perform primarily administrative roles or other non-patient-care roles (

24). Part-time staff were reflected as partial FTE staff in the data analysis.

The gross number of providers reported for the carve-out plan located near HMO A reflects the fact that providers may have contracts with such organizations without providing full-time services or any services. Thus it is difficult to estimate from contract data the number of lives covered per provider. Therefore we compared the percentages of contracting providers in various professional categories affiliated with the carve-out plan with the percentages of providers in the same professional categories at HMO A and B. This strategy focused the comparison on overall staffing configurations rather than the absolute numbers of providers.

Conclusions

Recent data from two HMOs and one mental health carve-out plan show the breadth of staffing configurations for mental health professionals operating within managed care settings. Data on trends from 1992 to 1995 in two group- or staff-model HMOs in Western states also demonstrate changes over time in the mental health workforce in integrated full-service HMO settings. The data show decreases in the number of psychiatrists as well as overall workforce reductions for other classes of mental health professionals in these two organizations in competitive markets.

The competitive climate of the managed care market may partially explain the observed changes in staffing ratios and the decline in the overall workforce. Markets with a high level of managed care penetration and increasing competition would seem to hold stronger economic incentives for economic substitution of certain workers for others. Furthermore, an increase in managed care penetration and the possibility that staffing ratios for certain mental health providers may be lower in staff-model HMOs than overall state or national ratios raise issues about the job market for recent mental health graduates. The growth in the number of new graduates of doctoral psychology programs (both Ph.D. and Psy.D. programs) and master's-level and doctoral programs in clinical social work far exceeds the number of recent U.S. medical graduates selecting psychiatry training (

29,

30).

The actual number of new doctoral-level psychology graduates totaled about 3,000 in 1996. This total included individuals trained in research psychology who will not enter clinical practice. The American Psychological Association estimated that 2,400 of these graduates trained in clinical specialties (

30,

31). In 1995 there were nearly 13,000 new graduate master's-level social workers and about 300 new graduate doctoral social workers. A smaller number of graduates are clinical social workers (personal communication, Council on Social Work Education, 1996).

The supply of graduates may reflect the needs of managed care organizations and behavioral health care plans and the reconfiguration of the market's demand for certain mental health professionals. Clearly graduates of all types may be entering markets with a shrinking demand for certain providers, at least in competitive markets in which the level of managed care penetration is high (

20).

Data were not available for paraprofessionals nor for the level of direct provision of mental health services by primary care gatekeeper physicians. Nor were we able to obtain specific diagnostic code data that might illustrate a change in type or frequency of mental health services by provider type, though such changes have been occurring in the industry in general (

32,

33,

34).

In light of this case study, some overarching questions come to mind: First, what staffing configuration will provide optimal efficiency and quality of mental health care, and does this configuration vary by organization type? How do these changes, seen in managed care settings at a local level, interrelate with reconfigurations in the national mental health workforce? Last, how could an increased focus on collaboration among provider types (including explicit training) improve the delivery and quality of services to patients and clients?

Evaluation, including outcomes measurement for newer models and teams of workers, is needed. Researchers within a practice setting could contribute to this effort. In addition, an important role for both psychiatrists and doctoral-level psychologists in hospital and managed care settings has become the supervision of master's-level mental health workers trained in such fields as psychology and marriage and family counseling (

35). Further research in managed care settings may demonstrate that economic substitution of nonspecialist physicians contributes to workforce reductions among mental health specialists. Research on staffing in other types of managed care organizations, such as carve-out behavioral health care organizations, as well as on workforce needs in the public mental health sector is needed.

In addition, documentation of decreases in staffing in competitive markets suggests that the output of all types of postbaccalaureate providers warrants reexamination. Rising numbers of clinical nurse specialists certified in psychiatry and capable of prescribing in many states represent another scenario ripe for economic substitution, but also the possibility of nursing specialists' forging a complement to other provider types.

Unlike the predominance of restricted provider panels in managed care organizations in the late 1980s, it now appears that all types of mental health professionals are practicing in managed care settings (

36). Directions for further research include continued monitoring of workforce reconfiguration in various types of managed care organizations and investigation of optimally efficient workforces that maintain patients' access to high-quality mental health care. With no one group of mental health professionals having a lock on service delivery, new, more collaborative models for care could evolve, reintegrating comprehensive mental health care into primary care settings.