Ideally, inpatient treatment for individuals with severe and persistent mental illness should be seamlessly integrated with community services so that hospitalization is brief and minimally disruptive and the services provided in the community can be continued without interruption in the hospital or resumed as quickly as possible after discharge. With the mandate to wring costs from all medical services including psychiatric care, coordinated inpatient and community treatment of seriously and persistently mentally ill individuals—long considered an ideal model of care—has become a necessity.

Unfortunately, coordinated care is far more the exception than the rule. Inpatient and outpatient facilities often have different administrative structures and clinical procedures, and each one's staff is reluctant to lose authority through the compromises implicit in integration. This situation places the responsibility for integrating care on the patients themselves by following through with community services after inpatient care, despite their less than optimum functioning at discharge. Regrettably, a review of 25 years of research and clinical studies concluded that the majority of patients with serious and persistent mental illness do not follow through with community care, with as many as 70 percent failing to make even their first postdischarge appointment (

1).

However, there is reason to believe that patients can be taught to actively seek and obtain their own comprehensive community care. Indirect evidence is provided by a study that found that higher rates of follow-up with community care were associated with a greater number of hospitalizations, longer length of inpatient stay, less denial of need for treatment by the patient, and the patient's greater perceived need for medications (

2). These results suggest that patients who are more experienced, knowledgeable, and accepting of their illness and its care will seek and obtain treatment.

The one study that provides directly relevant evidence used a quasiexperimental design with the community re-entry program (

3) that is also the focus of this study. That study indicated that inpatients not only improved their knowledge and performance of the information and skills presented in the program, but that their level of knowledge and performance at discharge was positively associated with their functioning two months after discharge. However, the one-group pre-post design of the study makes the results tentative. Also, the patients who completed the study were a small subset of a larger group of enrolled patients with a heterogeneous mix of diagnoses. Furthermore, the measure of postdischarge functioning was a rating by the authors of social workers' case notes written during the postdischarge period rather than a direct evaluation of patients' clinical status.

The study described in this paper was designed to evaluate the community re-entry program by comparing its outcomes with those of an equally intensive regimen of occupational therapy as the control intervention, with random assignment of participants to the groups. Outcomes were assessed by reviewing service records of attendance at scheduled aftercare sessions and measuring whether participants' knowledge and performance of the specific material and skills presented in the program increased. We hypothesized that individuals who participated in the community re-entry program would learn the material better and would have a higher rate of attendance at their first postdischarge appointment than their counterparts in the occupational therapy control group.

Methods

Participants

The sample comprised 70 individuals with a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were recruited from consecutive admissions to an acute psychiatric inpatient unit of a university-affiliated county hospital. Data are reported on the subjects who completed participation in either the community re-entry program or the occupational therapy group; completion was defined as attending at least four sessions.

Of this total of 59 participants—28 in the community re-entry program and 31 in the occupational therapy group—42 (71 percent) were male. Twenty-five (42 percent) were Latino, seven (12 percent) were African American, 23 (39 percent) were Anglo, three (5 percent) were Asian, and one (2 percent) was in a category "other." Their mean±SD age was 35± 11 years (range, 20 to 64 years). The mean±SD age of onset of the illness was 22±8.1 years, the mean duration of illness was 12±9 years, and the mean number of hospitalizations within the two years before the study was 2.5±1.5. Forty-eight subjects (81 percent) were unemployed.

Thirty-eight subjects (64 percent) returned after discharge to living with their families, ten (17 percent) established residence at a board-and-care home, one (2 percent) was discharged to independent living, six (10 percent) went to skilled nursing facilities, and four (7 percent) were discharged to miscellaneous residences.

Procedures

After receiving an explanation of study procedures, all consenting subjects signed an informed consent agreement before participating in the study. Following a brief period of symptom stabilization, diagnosis was confirmed by the first author using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (

4). Each participant took a preintervention test devised for the study to measure knowledge and performance of the material that would be presented in the community re-entry intervention. Participants were also asked for demographic information (age, ethnicity, duration of illness, number of hospitalizations, employment, and type of residence). They were randomly assigned to one of the two groups, and participation began either that day or the next.

The community re-entry program was conducted with groups of six to eight patients. Groups met four days a week, both in the morning and in the afternoon. Patients attended the group whenever they felt able and continued participation regardless of the actual sequence in which they attended the sessions. As soon as a specific time had been set for discharge, the trained interviewer arranged to readminister the test of knowledge and performance. The specific discharge residence and aftercare contact were also recorded. Participants attended a mean±SD of 6.8±2.1 sessions; half the patients began with the first session and followed the expected sequence.

Treatments

Community re-entry program.

The community re-entry program is based on the Social and Independent Living Skills Modules (

5) developed by the Intervention Research Center for Major Mental Illness at the University of California, Los Angeles and modified for use in the rapid-turnover, "crisis" operations of a typical acute psychiatric inpatient facility. The program consists of 16 training sessions each 45 minutes long, divided into two eight-session sections. Due to the short length of stay at the facility (about eight days), only the first section was conducted. These sessions were selected because they were described by the authors of the community re-entry program as "particularly relevant for patients who are preparing for discharge from the hospital" (

6).

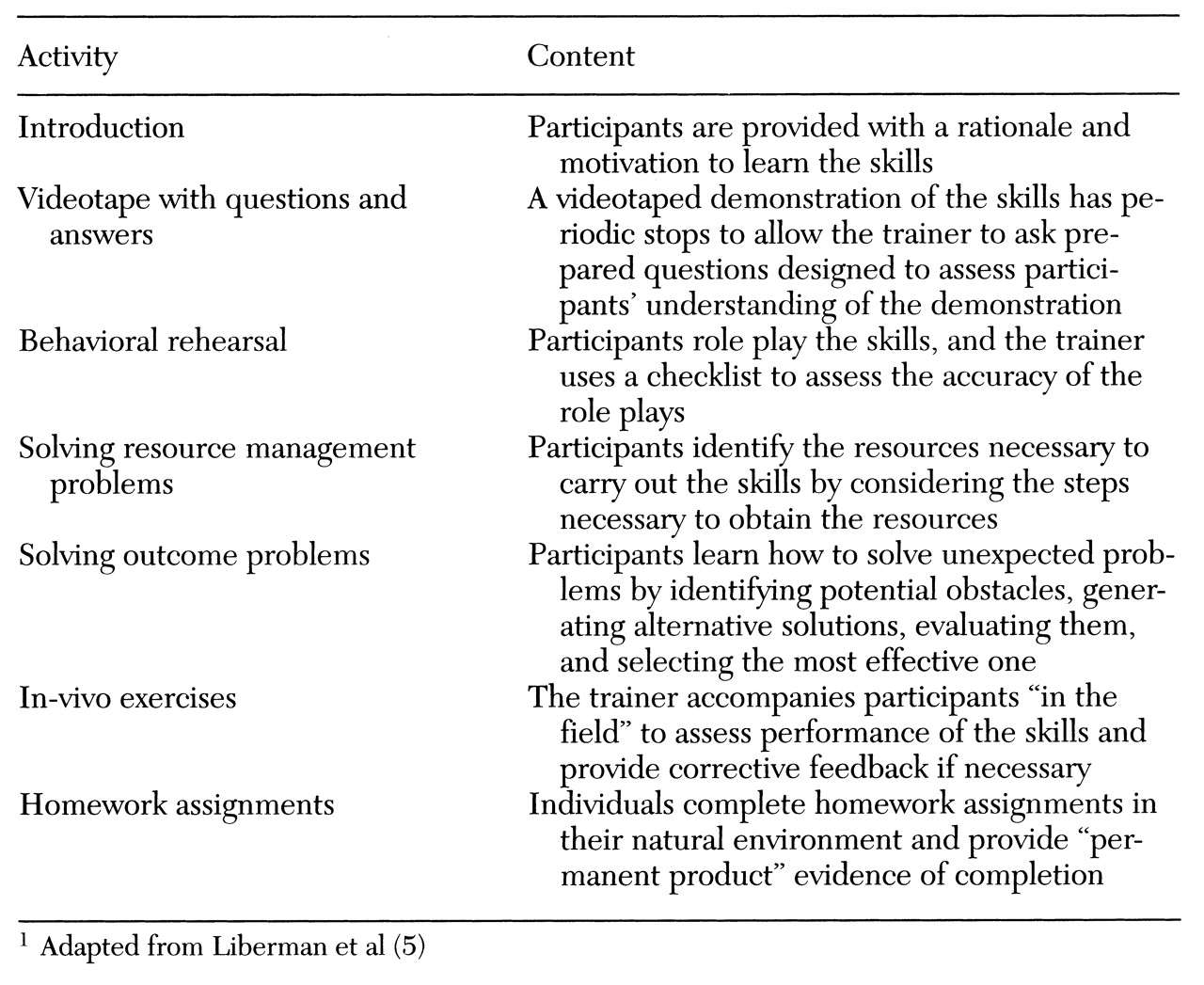

The first two sessions focus on teaching participants the knowledge and skills to understand their disorders and the medications that control it. The next four sessions help participants develop an aftercare treatment plan by identifying problems, specifying remedial and maintenance services, and linking them with service providers. The final two sessions address the skills needed to avoid illicit drugs, cope with stress, organize a daily schedule, and make and keep appointments with service providers. Each of the sessions are taught using the seven learning activities shown in

Table 1, which form the core of the modular skills training approach (

5).

All sessions of the community re-entry program were conducted with two trainers drawn from a cadre of ten staff. The staff represented a wide variety of disciplines, including nursing, occupational therapy, social work, psychology, and psychiatry. All staff members were relatively experienced in providing services to individuals with serious and persistent mental illness; each had a minimum of three years of experience. To rate the trainers' activities, one of the authors (RZ) monitored about 25 percent of the sessions using a fidelity measure derived from the form and content specified in the trainer's manual. Several prescribed behaviors were listed on a checklist (for example, "read the introduction to the skill area," "ask the questions in the manual," and "pause the videotape at the marked stop"), and the observer recorded whether the trainer performed the behavior; the results were summarized in terms of the percentage of prescribed behaviors performed by each trainer. All trainers performed at least 92 percent of the observed learning activities following the form and content specified in the trainer's manual.

Occupational therapy.

The occupational therapy sessions included the full range of customary occupational therapy activities conducted by two or three certified occupational therapists.

Measures

Test of knowledge and performance.

To determine if the community re-entry program achieved its teaching objectives, a test of participants' knowledge and performance of the material presented was administered before and after participation. The test consisted of 18 questions, problems, and role-playing activities administered by a trained interviewer. (The test is available from the first author.) The interviews during which the test was administered were videorecorded for later determination of interrater reliability.

Responses were scored according to explicit criteria stated in the test. For example, three test items focused on planning a daily schedule after discharge. One of the items asked, "Why is it important to stay active after leaving the hospital?" Acceptable answers included to stay well and avoid feeling down, depressed, bored, or lonely. The possible overall score on the test ranged from 0, for less than three acceptable answers on the 18 items, to 2, for five or more acceptable answers.

Attendance at aftercare service.

To determine if the community re-entry program achieved its clinical objective of improving continuity of care, data from the county's management information system was reviewed. Service records of participants during the month after their discharge were analyzed to determine if they had attended an aftercare session.

Results

No differences on any demographic or clinical variable were found between subjects randomly assigned to the community re-entry program and the occupational therapy group.

An analysis of the interrater reliability of the scoring of the knowledge and performance test was conducted by selecting 34 tests at random (20 preintervention tests and 14 postintervention tests from the same subset of participants) and giving them to a second rater who had received the same training as the primary raters. The second rater was blind to participants' group assignments and whether the tests were pre- or postintervention. The videotapes of the interviews were arranged in random order for the second rater. The total scores given by the two raters to the 20 preintervention tests were correlated, as were those of the 14 postintervention tests. The results showed high interrater reliability (r=.932 for the preintervention tests and r=.962 for the postintervention tests).

The change in mean scores on the test of knowledge and performance for the community re-entry group from pre- to postintervention was significant (from 55 percent correct to 81 percent correct; t=5.3, df=27, p<.001). The difference in scores between the two groups on the postintervention test was also significant (81 percent correct for the community re-entry group versus 55 percent for the occupational therapy group; t= 5.1, df=56, p<.001). The between-group difference on the preintervention test was not significant. The mean scores of the occupational therapy group did not change significantly over time (50 percent correct preintervention and 55 percent postintervention).

Subjects in the community re-entry program were significantly more likely than those in the occupational therapy group to attend their first aftercare appointment. Five participants, four from the occupational therapy group and one from the community re-entry program, were discharged to locked residential facilities and were thus excluded from this analysis. Of the 27 remaining participants in the occupational therapy group, ten (37 percent) attended the first appointment, compared with 23 of the 27 participants (85 percent) in the community re-entry program (Yates' corrected χ2 =11.22, df=52, p<.001).

Discussion and conclusions

The results indicate that the community re-entry program achieved its educational objective and led to a substantial and meaningful difference in patients' following through with their aftercare. The value of this enhanced follow-through was documented in Klinkenberg and Calsyn's review (

1) of aftercare treatment, which reported that an initial contact with community-based aftercare treatment was associated with lower rates of rehospitalization. Placing the responsibility and means to follow through in the hands of patients empowered them to be partners in their own care.

Of course, the value of the community re-entry program depends on the support of the inpatient clinical and administrative staff and procedures. This study's procedures were specifically designed to test the adaptability of the community re-entry program. First, all participants were acutely ill, and no special procedures were used to ensure that they were clinically stable before participating. Despite their illnesses, the community re-entry participants learned the material well, and only one patient dropped out of the group due to intolerance of the training procedures (length of the sessions). Each of the other six subjects who did not complete the training were discharged from the inpatient ward before they could attend the minimum of four sessions required for study participation.

The results suggest that rehabilitation procedures such as skills training can begin in the hospital and continue without interruption in the community and that inpatient and outpatient facilities can be linked in a common treatment philosophy and a set of treatment techniques.

The second test of the community re-entry program's adaptability was that sessions were scheduled to meet the needs and preferences of the staff. In the trainer's manual (

6), the material is presented in an unvarying sequence. Even though the concepts taught in the community re-entry sessions are interlocking, the learning of the participants in our study who began and ended in "midstream" was identical to that of the participants who followed the prescribed sequence. This outcome was shown by a split-plot factorial analysis of variance with scores on the test of knowledge and performance as the dependent variable, pre- and postintervention scores as the within-subjects variable, and midstream versus prescribed sequence as the between-subjects variable; the analysis showed no significant difference in the learning of the midstream subjects.

The third test of the community re-entry program's adaptability was that it was conducted by a wide array of staff members, all showing excellent fidelity to the specified procedures. The highly structured and thoroughly specified format of the materials minimizes the time and costs of training, encourages the substitution of trainers in the event of absences and emergencies, and opens the program to all staff members, not just professional staff, who are usually in short supply.

The major limitation of this study was that subjects were followed for only one month after discharge from the inpatient ward. Although community re-entry training increased the attendance rates for the first postdischarge appointment, follow-through with the first aftercare session in no way guarantees that continuing care will be effective. To address this concern, we are following the participants in this study for one year, gathering data on the utilization of outpatient and inpatient resources.

We recognize, of course, that a host of factors determines the effectiveness of continuing care, not the least of which is the quality and quantity of contacts between a patient and the continuing care providers, as well as the supportive nature of these relationships. However, continuing care cannot be effective until the patient follows through with aftercare regardless of the vagaries of the system of care and the lack of integration among its many elements. Teaching patients to follow through and informing them about serious and persistent mental illness and the need to become an active collaborator in continuing care is a worthwhile step to improving long-term outcomes.