Consumer empowerment might be considered to have begun with the public writings of individuals hospitalized in lunatic asylums in the 19th century (

1), or with early-20th-century psychiatric patients turned crusaders (

2), or with the birth of Fountain House at midcentury (

3). However, it probably began as the“ex-patient movement” of the early 1970s, graduating to“consumer empowerment” about 15 years later (

4).

During the consumer empowerment movement, some individuals who have a history of serious mental illness and who are heavy users of psychiatric services have moved from the role of patient to that of provider. Such positions have included case managers (

5–

8), community support workers (

9–

11), program evaluators (

12,

13), crisis workers (

14), board members (

15,

16), peer counselors (

17,

18), and mental health professionals (

19).

Although this progress has often occurred in local mental health agencies, the question that interested us in undertaking this survey is what role state governments have played through their state mental health authorities. In a May 1995 press release, the director of the Division of Mental Health, Mental Retardation, and Substance Abuse in the Georgia Department of Human Resources proclaimed that Georgia“hired more consumers than any other state because our program managers really believe this is important” (

20). Georgia's self-acclamation may or may not be true. No source of data was cited to substantiate or refute this or any other claim concerning states' roles in consumer empowerment. Therefore, we conducted a national survey to ascertain what states were actually doing.

Background

Before describing the survey methods and results, it is helpful to consider the term consumer empowerment. Why use the label consumer? And what does consumer empowerment mean?

The term “consumer”

The term consumer is one in a long list of labels that users of psychiatric services have applied to themselves. Such terms include client, consumer, customer, patient, ex-patient, psychiatric survivor, and consumer-survivor. Some professionals have made efforts to understand the underpinnings of the term consumer (

21,

22), and other professionals have strongly criticized its use or its implications (

23,

24). Mueser and colleagues (

22) conducted a survey in 20 different mental health service sites in five states, asking users of the services what term they preferred professionals to apply to them. Forty-five percent preferred the term client, 20 percent preferred patient, and only 8 percent preferred consumer.

Users of psychiatric services publish material indicating very different feelings about the term consumer. Stocks (

25) wrote that when the term was first applied to her,“it made my skin crawl.” Chamberlin (

4), who once championed use of the term consumer, indicates that most patients and ex-patients are not even familiar with the issues or the debate about which term should be used.

In light of these findings, we use the term consumer when it applies to consumer empowerment, because this term appears to be preferred by people involved in empowerment efforts. Otherwise, we use the term client to refer to users of psychiatric services because this term seems to be the preference of the majority.

Consumer empowerment

Between 20 and 30 years ago Rappaport (

26), a proponent of the study of empowerment by American psychology, indicated that empowerment included individual determination over one's own life and democratic participation in the life of one's community. He maintained that empowerment is both a psychological sense of personal control or influence and an interest in actual influence—social, political, and legal. Rappaport also proposed that the movement from“helpee” to helper, especially within peer organizations, empowers a person. Finally, one of his conclusions was that“other things being equal, an organization that holds an empowerment ideology will be better at finding and developing resources than one with a helper-helpee ideology,” partly because "empowerment is not a scarce resource that gets used up.”

Consumer empowerment per se has been examined by professionals (27-30), consumers (

4,

31,

32), and a few who identify themselves as both a consumer and a professional (

15,

33,

34). These sources have led us to define consumer empowerment as the status in which psychiatric clients:

•

Form their own independent social networks not dependent on professionals for social support

•

Use professionals for technical assistance to make better decisions themselves in environments where they exercise full participation in decisions affecting their own lives

•

Participate in treatment with professionals and paraprofessionals as collaborators, not as passive people receiving treatment, where they are seen as the primary informants about what is wanted and needed from providers

•

Are respected for the legitimacy of their points of view, which are not written off as just a product of their illness

•

Are using resources from the entire community and not just the formal mental health system

•

Are operating within a health-promoting system

•

Have significant input beyond their individual treatment into decision making at program, agency, community, state, and federal levels

•

Achieve a sense of self-responsibility

•

Are sure that consumer empowerment is more than just a buzzword.

Methods

A survey was sent to the commissioner of mental health in each state in the United States and in the District of Columbia, as well as in the U.S. territories and commonwealths of American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, Northern Mariana Islands, and the Virgin Islands. The survey asked questions about the state's official handling of the policy of the least restrictive alternative and consumer empowerment and responsibility. With repeated reminders to some jurisdictions, we obtained a 100 percent response rate. The survey was mailed in October 1995, and the final response was received in June 1997.

We report here on only that part of the survey related to consumer empowerment and responsibility. The survey asked whether these matters were mentioned or defined in state statutes or regulations or in policies of the mental health authority. If so, states were asked to send all applicable documents. The survey also inquired about the number, if any, of consumer or family members employed by the central office and field offices (regional and county) of the mental health authority in positions designated for them. The family member positions were limited to those involving adult services.

Responses to the survey were collated and analyzed using frequency statistics. When states sent documents, the text was entered into an Access database program.

We created a rating scale for the states and territories reflecting the number of relevant policies and the number of paid positions in the central office and in field offices: 0, no policies and no paid client or family position; 1, one policy and no paid position; 2, two policies and no paid position; 3, no policies but at least one paid position in the central office for a client or a family member; 4, no policies and at least two positions for a client or a family member in the central office, in a field office, or one in each; 5, one or two policies and at least one central office or field office position for a client or a family member; 6, one or two policies and at least two positions for a client or a family member in the central office, in a field office, or some in each; 7, one or two policies and at least one position for a client and one for a family member in either the central office or a field office, plus a position for a client or a family member in the other location.

We then compared these rankings with other variables that might be related to these policies and positions, including state population (

35), region of country, the state's mental health budget for total expenditures (

36), and the last ranking of the quality of the state's public mental health services by the Public Citizen Health Research Group and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (

37). Analysis of variance was used for regions of the country and a Spearman rank-order correlation for all other variables.

We asked states if the state mental health authority had regular meetings with empowerment groups in the state, and whether they had meetings with these groups on an as-needed basis. Finally, we allowed space for states to provide any other information the state deemed relevant to our survey.

Results

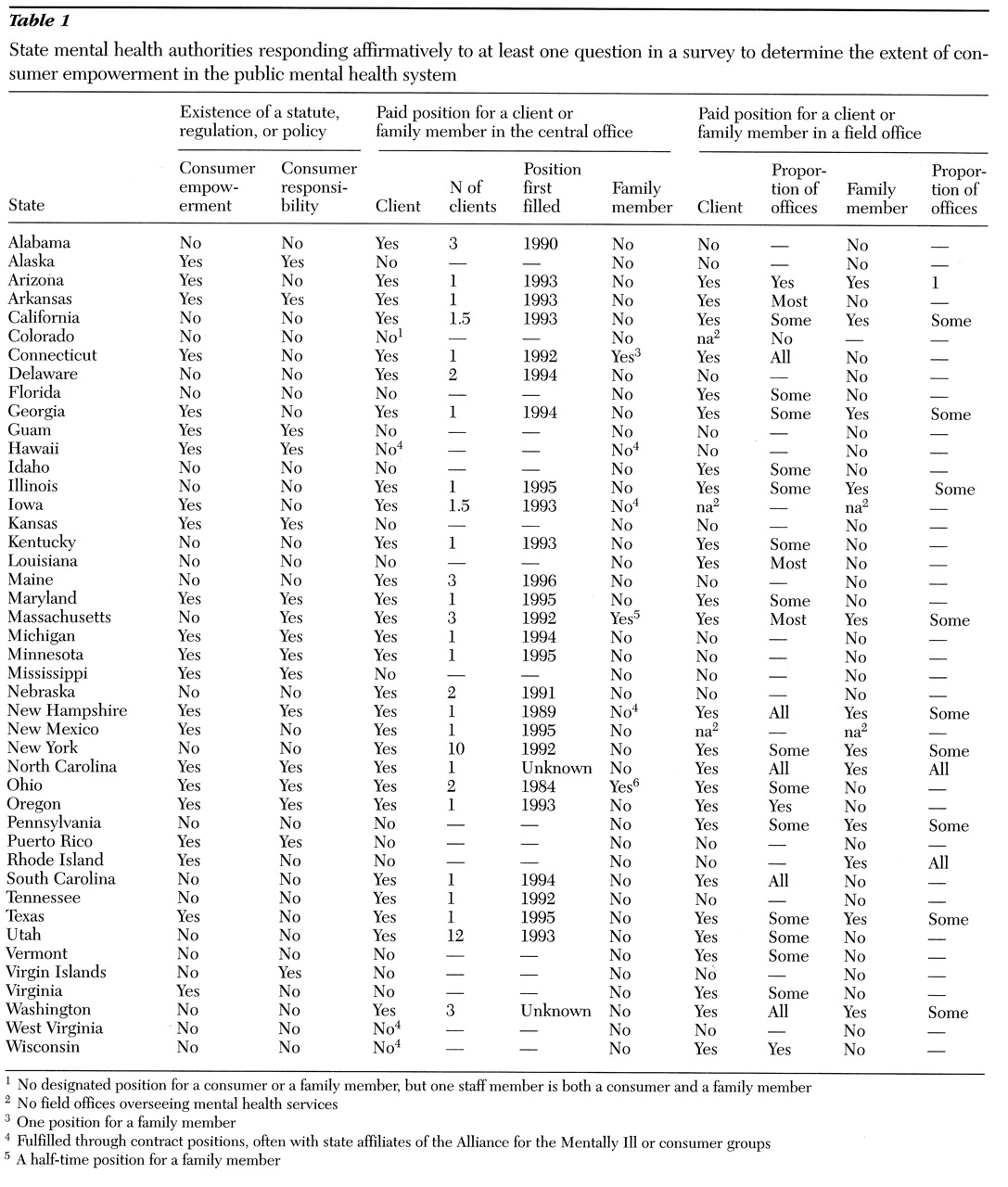

As shown in

Table 1, responses of states and territories—referred to hereafter as states—indicated that 39 percent (22 states) have a statute, regulation, or policy that covers consumer empowerment, while 28 percent (16 states) have a statute, regulation, or policy that covers consumer-client responsibilities. Thus policies to address responsibility lag behind those to address empowerment.

Table 1 also presents the states' responses to the question about the existence of a position for a consumer or a family member in the central office of the mental health authority. Forty-eight percent of the states (27 states) reported that a paid position for a consumer existed in the central office. Paid positions for family members in adult services in the central office were far fewer, reported by 5 percent of states (three states).

Table 1 also lists responses to the question about paid positions for consumers and family members in field offices. Paid positions for consumers in field offices existed in about half the states. The question asked how many positions for a consumer existed. A few states answered with a number, and most states indicated that a position existed in some, most, or all of the field offices: 28 percent (14 states) reported some, 6 percent (three states) reported most, 9 percent (five states) reported all, and 6 percent (three states) simply answered yes. Six states were excluded from this analysis because each indicated the state's organization of public mental health services did not include field offices.

States had fewer paid positions for family members in field offices than for consumers. Twenty-five percent (12 states) responded yes to the question about whether they had such positions; 18 percent (nine states) reported that positions for family members existed in some field offices; 4 percent (two states) indicated that all field offices had such positions; and 2 percent (one state) indicated that it did not know. Six states were eliminated from this analysis for the reason cited above.

Ninety percent (51 states) indicated that the state mental health authority held regularly scheduled meetings with empowerment groups, and the same percentage reported as-needed meetings with such groups. States reported meeting most commonly with statewide or local affiliates of the Alliance for the Mentally Ill (AMI). Each state met with groups with names particular to that state; some of them may be parts of national organizations, and others are not.

For example, the Alaska authority reported meetings with Alaska AMI, the Alaska Consumer Association, the Alaska Mental Health Association- Consumers, the Disability Law Center of Alaska, the Alaska Mental Health Board (50 percent consumer representation), and Mental Health Consumers of Alaska. The Massachusetts authority reported meetings with the Office of Consumer and Ex-Patient Relations; Massachusetts People Organized for Wellness, Empowerment, and Recovery (M*Power); the Clubhouse Coalition; the AMI Consumer Council; the Manic Depressive and Depressive Association of New England; Boston University Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation; and many local groups. Virginia reported meetings with Virginia AMI, Virginia Mental Health Consumers Association, the Mental Health Association of Virginia, the Board of Rights of Virginians With Disabilities, Mutual Education Support and Advocacy, and others.

States were given the opportunity on the survey instrument to make other comments about the mental health authority's involvement with clients. Several states (for example, Kansas, Louisiana, New Jersey, and Oklahoma) indicated that they provide substantial financial support to consumer organizations and activities. Alabama stated that it has a policy to encourage selection of qualified clients to fill vacancies throughout the system operated by the Alabama Department of Mental Health and Retardation. Kentucky indicated it had developed a consumer advocacy council that meets regularly to improve policies and services for clients in hospitals and the community. The council's membership is predominantly clients, with the addition of a few professionals.

Rhode Island reported that consumers and family members turned down the opportunity to have positions in the state mental health authority but elected instead to take the funds and add staff to their respective organizations. Florida cautioned that all states should include former substance abusers in their cohort of client employees, particularly because of the high co-occurrence of mental illness and substance abuse.

Using the 8-point scale we devised, the states received a mean±SD overall score of 3.11±2.46 for the extent to which they have policies and procedures covering consumer empowerment and offer paid positions for consumers or family members in central and field offices. An analysis of variance showed no significant differences in regional scores. A Spearman rank-order correlation (rs) was used to examine differences in scores according to per capita expenditure by the state mental health authority, using five expenditure categories: less than $75, $75 to $99, $100 to $124, $125 to $174, and more than $175. No significant differences in states' scores were found by category. In other words, states that spent more to provide mental health services were not more likely than states that spent less to have policies covering consumer empowerment or to offer positions for clients or family members.

On the other hand, a relationship was noted between our score and the states' census. The larger the state population, the higher the score on the presence of policies and paid positions (rs=.5266, p=<.001, two-tailed).

A statistically significant correlation was also found between our score and the rating given to the state by the Public Citizen Health Research Group and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (

37) (r

s=-.4349, p=.003, two-tailed). The negative correlation is due to the fact that on our scale higher scores indicated more policies or positions while in the other rating system 1 was the highest rating and 50 the lowest. The significant correlation means that states ranked as providing better-quality services also scored higher on our scale of consumer empowerment.

Discussion

In this paper we have provided what we believe to be the first national data on the prevalence of consumer empowerment practices in public mental health agencies, which we have operationally defined as the inclusion of consumers by those agencies in their formal organizational structures. Our data show that consumer empowerment has gained considerable momentum in the mid- to late 1990s, although it is by no means universal across states.

Examining a number of correlates of state and county consumer empowerment reveals an interesting and somewhat provocative pattern. We observed that states with large populations were more likely to report consumer involvement, as were those that had obtained favorable ratings of state mental health services from the Public Citizen Health Research Group and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. However, no correlation was found between the extent of consumer empowerment in the state and the state mental health agency's overall per capita expenditures for mental health services.

This research is clearly preliminary, and even the correlations we have observed are open to a considerable range of interpretation. It is nevertheless important to consider the factors that might underlie these findings. The correlation with state population could be due to the fact that states with larger populations have greater overall tax bases and perhaps greater levels of discretionary funds available to support consumer involvement. However, the nonsignificant relationship between empowerment and per capita funding suggests that it is not simply the“richer” agencies on a per capita basis that engage in these practices.

It may also be that states with large populations have greater absolute numbers of consumers, which in turn allows greater opportunities for the development of consumer groups that can successfully advocate for their inclusion in public mental health organizations. Exactly how the decision is made by state or county mental health authorities to implement such empowerment is unclear and would make an interesting focus for research.

The observed positive correlation between consumer involvement and the rating given to the state by the Public Citizen Health Research Group and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill is interesting from a number of perspectives. From a statistical standpoint, the relationship is a statement of correlation, not causality, and numerous antecedent factors could be at work. The simplest interpretation is that state mental health authorities with organizational values that predispose them to involve consumers in their administrative structures are the ones likely to do other things that would win them positive ratings of the quality of their services. If we were to develop quantitative measures of such values and perform a factor analysis or other such procedure that looks for underlying dimensionality among a set of variables, we would likely find that our empowerment measures would load on factors together with other variables that represent “progressive”or valued approaches to the delivery of services.

Putting aside for a moment the question of factors with which empowerment might be correlated, it is useful to consider the nature of the relationship between empowerment and other agency orientations. Two causal models might be postulated. One—perhaps the more likely of the two—is that mental health agencies with positively valued practices in other areas have an orientation that predisposes them also to empower consumers. An alternative model posits an optimistic scenario in which mental health agencies that have empowered consumers by employing them in formal organizational roles have been influenced by them and are therefore more likely to engage in more highly rated service delivery practices. An analysis of the timing of public mental health authorities' consumer empowerment practices relative to other policy initiatives would shed light on this issue.

Understanding the true nature of the relationships observed among the variables we have examined would require that we learn much more about how and why mental health authorities empower consumers in the ways we have described. Additional research should focus on how consumers in state or county mental health authorities influence policies, contribute to dialogue, and represent the consumer perspective and should complement recent work done on defining consumer empowerment from the self-help movement (

38).

We also need to understand if and how policies and practices that have been influenced in their development by consumers better serve clients' clinical needs. Potential findings of weak relationships among these domains would be discouraging, perhaps, but should not deter such investigation. Indeed, whenever representatives of previously disenfranchised groups have been brought into the organizations charged with serving them, concern has always arisen that tokenism rather than real empowerment was either the intended or the unintended outcome. Before we accept current practices as true consumer empowerment, we need to know their extent and effects, lest we simply take empowerment's putative benefits as a matter of faith, as we have with so many other ideologically driven exercises in mental health system reform.